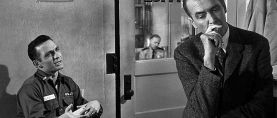

Shadows: Experimental Film Venture

Looking at John Cassavetes’ directorial debut — a film pieced together on the fly that resulted in extensive critical praise.

In a recent issue of American Cinematographer an article titled “The Experimental Film” (AC, January, 1961) made the point that, while such cinematic sorties are rarely commercial successes, they nevertheless are valuable contributions in filmmaking in that many are possible trailblazers to fresher, more vital motion-picture techniques.

Shadows, the initial directorial effort of actor John Cassavetes, is a phenomenon among experimental films in that, despite the fact it was never intended for theatrical release, it nevertheless is currently enjoying a successful run on the art-film circuit — a circumstance which should considerably increase the material worth of its surprised producers.

Moreover, it has garnered several international awards, including the Venice Film Critics Award for 1960, plus the plaudits of such authorities as New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther, who described it as: “Dynamic... Endowed with raw, vibrant strength... Incontestably sincere!”

Other critics have managed to contain their enthusiasm, pointing out that the film’s narrative frequently rambles in confused and tedious circles, and that the technical quality of sound and photography “leaves much to be desired.” The controversy reaches a peak in regard to the basic premise of the film’s approach — that of improvisation. Detractors point out that the device of improvisation is anything but new, having long been the mainstay of home movies, as well as of Roberto Rossellini, who used it with stunning impact in Open City and with considerably less success in Paisan and several subsequent efforts. Such critics are not at all certain that the art of the cinema is exalted by allowing actors to make up the plot and dialogue as they go along.

All of these criticisms have undoubted validity — and yet, Shadows emerges as an experience which continues to haunt the viewer long after he has left the theater. While it is, indeed, frequently confused and self-conscious in pattern, its champions maintain that so, also, is life itself, and that the aim of this film is to mirror life with its manifold irrelevancies, erratic tangents and frequent stretches of boredom, as well as its flashes of sharply focused drama. Whatever can be said on the negative side, the film has several stunning moments of truth — moments which seek neither to preach nor prove, but simply to call attention to the critical mass of emotion which frequently touches off an explosion in the lives of so-called “ordinary” people.

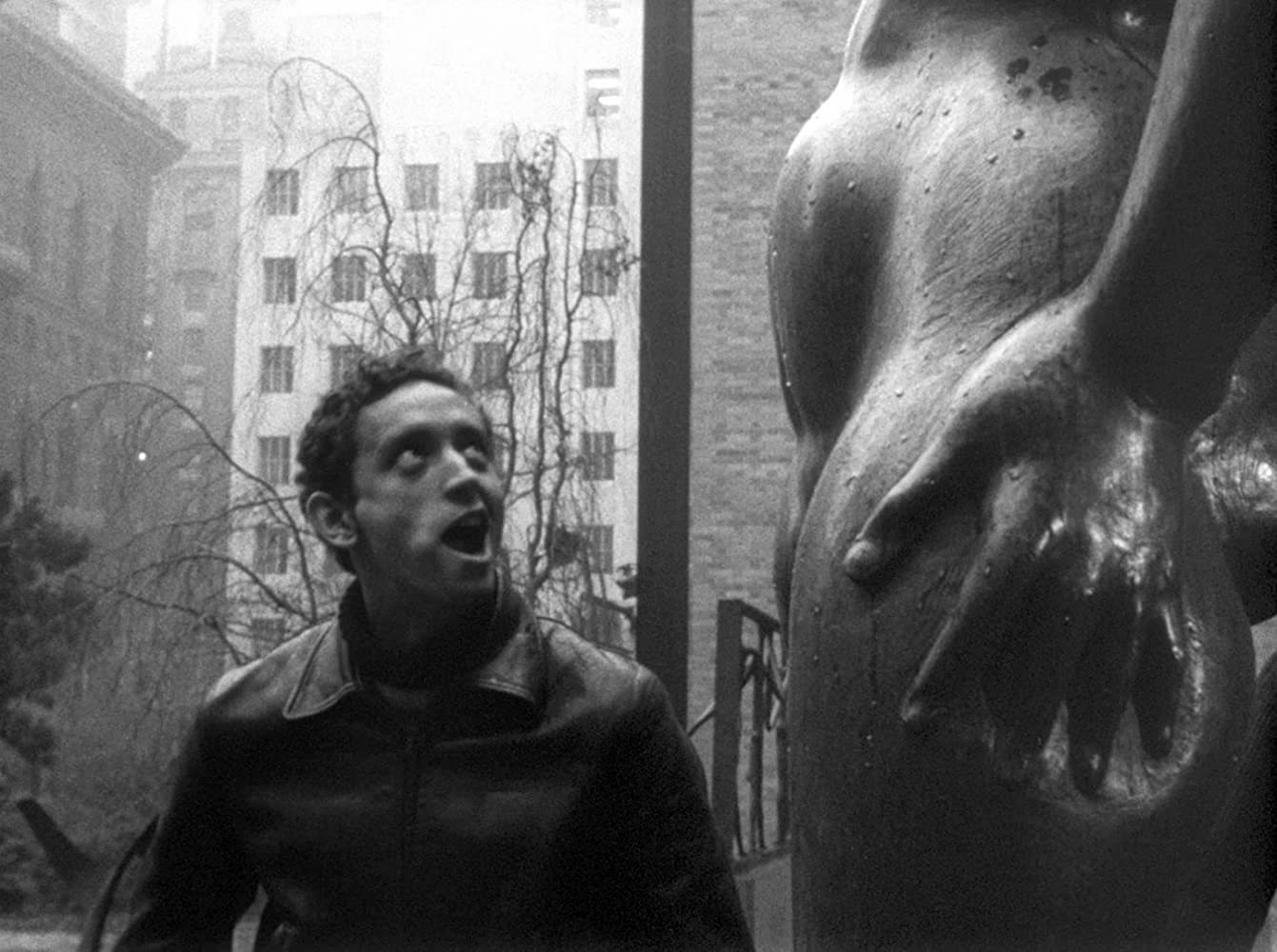

The picture begins, aptly enough, in confusion. The camera wanders about Manhattan, nibbling at slices of life, pausing to look at one undefined character and then another. Finally, at a party, it lights on a young woman somewhat the worse for champagne. A brash young man engages her in won’t-take-no-for-an-answer conversation, lures her to his apartment and seduces her. Although disillusioned by this less than idyllic experience, she nevertheless decides that she loves him, and vice versa, until he takes her home, meets her family and discovers that she is colored. His acutely painful embarrassment and withdrawal reaches a peak of dramatic intensity. And when, finally, he attempts to apologize for his shocked reaction it is already too late. The camera returns whence it came, into the boredom and loneliness of the world’s most exciting city. There are no messages, no moral preachments nor anything that might be termed socially significant.

to 35mm and given national theatrical

release. As a result of the picture's

success, Cassavetes was made a director

at Paramount Pictures in Hollywood.

What is perhaps more interesting than pro and con arguments as to the film’s technical quality are the details of how it came into being in the first place. It began as a vague idea back in 1957, when Cassavetes was conducting a dramatic workshop in New York in a West 46th St. loft. Students attended sessions there with the object of learning as much as possible about the acting craft. They studied stage technique, but there was no place they could go to get experience in acting for the camera. Cassavetes had appeared in many films as an actor, but he was anxious to find out what things were like behind the camera. Other students wanted to try their hands as cameramen, sound technicians, etc., in order to get an idea of what the technical crew was going through behind the lens while they were being temperamental in front of it.

It was decided that the actors would benefit most by improvising scenes, so there was no script nor written dialogue. The group spent three weeks discussing general theme and trying to establish characters. They would also take off to make life studies in actual locales, observing bartenders, B-girls and other potential types in their natural habitats.

Finally, filming got under way with a borrowed 16mm Arriflex camera synchronized with an RCA-Victor ¼-inch tape recorder. The nominal cameraman was Erich Kollmar, whose sole previous experience was gained in shooting a documentary film in Africa. However, when he could not be present, whoever happened to be handy took over the camerawork. The same democratic procedure applied to sound and other technical skills.

Since no dolly was available, a 6-inch telescope lens was used to make shots to take the place of what would ordinarily have been trucking shots. The results are somewhat odd on the screen. Two actors, for example, walk the length of a city block toward the camera against an unchanging background and without seeming to get any closer — almost, in fact, as if they were walking on a treadmill. The same alternative was resorted to when it was necessary to follow actors through crowds and across streets.

Most of the interiors were shot in sets constructed on the stage of the group’s headquarters. Some of these sets (notably the girl’s apartment) appear to have been hammered together out of old orange crates, and it could be argued that a more realistic effect might have been achieved by shooting in actual locations. Lighting on the stage was no problem at all; the movie makers simply papered the ceiling with aluminum foil and screwed ordinary 150-watt household-type bulbs into the sockets. The result was an overall f/4 light that softly suffused the entire set. Several interior sequences were shot in bars along Eighth Avenue, and these areas were lighted with photoflood lamps. Along the way the exposure meter became lost, and so the intrepid cameramen carried on without it, blithely estimating exposure as he went along!

A crisis was reached when the group ran out of money. Cassavetes discussed the project in an on-air interview with Jean Shephard on the Night People program. Shepard appealed directly to his audience. “There must be thousands of men and women who would like to know they could help to have a movie made,” he mused wistfully, and a total of $2,500 poured in from the audience. Later, a fresh appeal was made and cash arrived from people like Joshua Logan, Hedda Hopper, Jose Quintero, William Wyler, Reginald Rose, Charles Feldman, Robert Rossen and Sol Siegel. The rest of the budget of $40,000 was borrowed.

For 42 days and nights, the avid thespians trailed around New York, shooting from the neon-bright marquees of Broadway theatres and from disguised dustbins. Because they had no license to shoot in public places, they concealed the camera in subway entrances, restaurant windows and the back of trucks. They were constantly on the run to elude police because they did not have the required permit. The permit would not have been a problem had they been able to scrape up enough money to buy the required insurance.

One night they were preparing to film the brutal fight sequence which climaxes the film. They wanted to shoot in a certain alley, so they carefully went around and secured permission from all of the people in the neighborhood. They were all set up in the alley, just starting to shoot the sequence by available light. The fight no sooner started when a police car suddenly drove up, sirens blasting. Cassevetes talked his way out of that one by saying that the people in the neighborhood had given them permission to shoot. When questioned by the police, the neighbors admitted they had given such permission but had, in the meantime, changed their minds and did not want any further disturbance. The actors now had to sneak away and find another location — this time an areaway behind a bar just off Broadway. The fight as it reaches the screen is a triumph of realism, and it is amazing that actors who were not professional stunt men could have worked it out in such authentic detail without actually killing off several of the participants.

In improvisation without rehearsal or definite action pattern it would seem probable that the cameraman would go out of his mind trying to follow the actors but, surprisingly, he had no such trouble. It was discovered that the natural movement of human beings is easy to anticipate and to follow, whereas planned and rehearsed movement is often very difficult. Even though there were some very difficult pan shots to follow figures racing up and down streets and through Central Park, not one shot had to be re-taken.

A most unorthodox procedure of shooting was used in photographing the improvised action. Instead of shooting a master shot of a scene first and then getting closeups to match, a reverse technique was used. The actors were briefed on the general sense of the scene and the relationships were reviewd. Then the camera would move in for a closeup of one of the actors, while the others fed him lines offscreen. The cameraman would run off the entire 400' of film, so that the actor had an opportunity to get off his chest everything he wanted to say on the subject. Then another actor would be filmed in closeup. By the time it was necessary to shoot the master scene, the actors had the action and dialogue pretty well crystallized in their minds, had discarded much of the extraneous business and could go through the entire scene with some semblance of coherence.

Cutting all of this together with any sort of flow was something else again. The surgery took a year and a half with the editor tearing his hair out when he discovered that a character might be wearing a shirt, a coat and a sweater, each in separate scenes that had to be intercut within a sequence.

Much of the improvisation that could not be made to fit into any sort of continuity was simply discarded. The finished film was shown for the group and their friends and then put on the shelf, where it remained for a year.

Later, Cassavetes happened to be in London working on a film. A representative of the National Film Theatre who had heard about Shadows approached him for permission to show the picture at a seminar on experimental film. The rest, as they say, is history. Britain’s top critics attended the showing, liked the film and praised it highly in the press. The result was that British Lion Films offered a sizable advance for rights to distribute the picture on a world-wide basis. After six months of legal red tape — during which all of the actors had to be contacted to sign releases and peace had to be made with the unions — the film was blown up to 35mm, an appropriately improvised jazz score by Charlie Mingus was added to the sound track, and the film was put into general release.

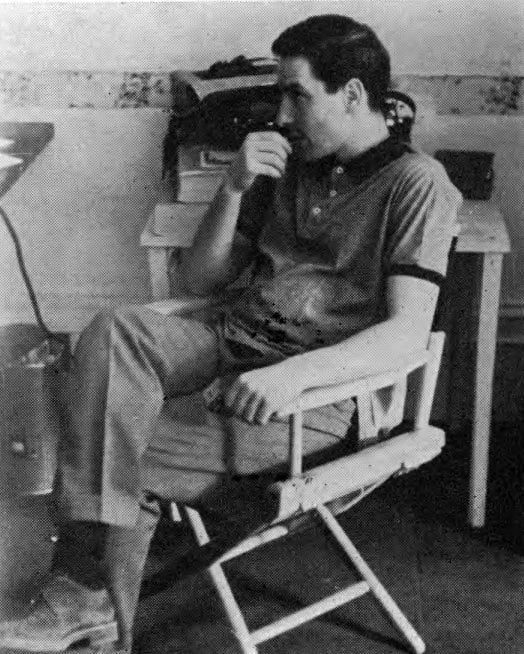

Meanwhile, those associated with the project have fared well. Several of the actors have landed roles and contracts as the result of being seen in the film. John Cassavetes was signed to a directorial contract at Paramount Studios where he had just completed his first assignment, Too Late Blues, starring Bobby Darin and Stella Stevens and photographed by Lionel Lindon, ASC, whom Cassavetes describes as “an extremely artistic cameraman, with a tremendous amount of guts.”

Cassavetes leaves soon for Rome to direct Paramount’s $3 million production The Iron Man. Not a bad ending for a 16mm filming venture.

In the decade following Shadows, Cassavetes would go on to star in such films as The Killers, The Dirty Dozen and Rosemary's Baby. He would also go on to direct 11 more features and numerous TV projects before his death in 1989.

The Paramount feature project mentioned at the end of this story, The Iron Man, was never made. Cassavetes instead directed A Child Is Waiting (1962) for United Artists, collaborating with Joseph LaShelle, ASC.