How Do I Find a Mentor?

This is a question I’ve been asked at least a hundred times by aspiring cinematographers eager to learn more, advance their careers, and receive guidance from someone who is already established.

This is a question I’ve been asked at least a hundred times by aspiring cinematographers eager to learn more, advance their careers, and receive guidance from someone who is already established — especially someone they aspire to emulate.

It’s actually a fairly easy question to answer, but it somewhat falls in line with the old joke:

“Excuse me, can you tell me how to get to Carnegie Hall?” asks the young man hurrying down the street.

“Practice, practice, practice,” replies the sage.

How do you find a mentor?

You don’t. One finds you.

Yes, I can hear your groans from here. But bear with me while I explain.

To do so, I’m going to talk about my own experiences as a mentor and what that word means to me, personally. I did not have a mentor in my career. Although I’ve had friendships and connections with many extraordinary filmmakers and cinematographers, I did not connect with one individual who “took me under their wing” to help guide me through the treacherous waters of this business. The way that I mentor individuals reflects how I would have liked to have been mentored by someone and the guidance that I wish I’d had.

I’m also going to make some suggestions as to how to follow some “rules” and improve your chances of acquiring a mentor.

Caveat: I am not currently in the market for a new mentee or protégé.

What is a mentor?

To me, a mentor is someone who takes another person under their wing and not only teaches the person, but also influences and guides his or her path. Different people interpret this in different ways. For some, a mentor might mean someone you get to sit down and have lunch with once a year who gives you advice and answers questions. To another, a mentor might be someone you can call or email periodically to get advice/answers. To another, it might be a more formal teacher/student relationship at an institution, with that teacher dedicating more time to the student and staying in touch outside of class and after the student has graduated.

To me, mentorship is a lifetime responsibility. It’s the mentor’s job to help shape the individual, teach them what they need to know, and guide them on the perilous path of this industry. That’s a commitment of years, and it’s no small ask. In order for me to take on a mentee, several factors have to be in place first.

I need to know the mentee personally

If I don’t know you, why would I make a commitment to dedicate years of my life to forming a bond and a relationship with you? What would motivate me to share years of hard-earned knowledge and experience; to answer questions of all kinds; to spend hours, days and months sharing the craft and helping you hone your own skills and talent? This is key, and it is not something you can skip over. This means I have personally known every individual I’ve taken on as a mentee. I have an idea of their personality, and they are someone I like and don’t mind spending time with. They are someone I respect. They are an individual of good character, generous heart and open mind (more on this later).

Tips

If you’re looking for a mentor, you need to get yourself into situations where you can meet and get to know the individual you hope to be mentored by. Show up to events they attend and be sure to make contact. Ask insightful and intelligent questions. Research the individual and find something you have in common. Are you from the same hometown? Did you attend the same school? Do you have the same personal interests

They love to sail? So do you!

And don’t lie about this; don’t fake it. Find a genuine personal connection if you can.

Don’t fawn. Don’t be a pest. If they’re speaking somewhere, make a point to attend and, if you can, say “hello” at the end of the event. If you aren’t in the same city/state/country, try social media. Many of the top cinematographers have their own social-media accounts. Try to comment on their posts with insightful questions. Try the direct-message approach. An individual who is open to serving as a mentor will most likely be open to these contacts and answering your questions. If the person you’re targeting for mentorship doesn’t attend events and doesn’t respond on social media, your chances are extremely slim, and you might want to try someone else. Generally, such individuals aren’t open to extensive mentoring, either.

In the end, it all starts with a personal connection, so it behooves you to create one. Don’t be overly aggressive! Don’t be creepy! Don’t send personal photos or make weird comments. Keep it professional! If the individual responds to you, then you have the first stages of establishing a relationship — but don’t read too much into this too quickly! It’s possible they respond to a lot of people, and one message (or even half a dozen) doesn’t make you best buddies. Social media can work, but there’s nothing like face-to-face contact. This is the key reason to live in a city that’s a major production hub: so you can connect with individuals who are at the pinnacle of their professional careers and might be able to help you.

Once you’ve had repeated contact, ask if you can take them to coffee to seek their advice. If you don’t live in the same city, perhaps ask for a 10-minute phone call or Skype call. DO NOT ASK THEM TO BE YOUR MENTOR. In the same way you wouldn’t ask a date to marry you within minutes of meeting them, don’t ask someone to make a major commitment to you without establishing a strong base first.

Additionally, the venerable six-degrees-of-separation rule is very powerful. Do you know anyone who knows them personally? A mutual friend who can introduce you and your hoped-for mentor is a very strong way to make that personal connection. Someone your potential mentor knows and trusts can help you form a strong bond quickly and shortcut a lot of more “casual” encounters.

The mentor needs to know your work and your talent

This one is also huge. If I’m taking on a commitment to someone, I need to know they’re worthy of my time and effort. I need to see that they have talent and drive. They can’t be lazy; they can’t be complacent; they have to be a go-getter. I need to see a reel and work that impresses me. Even early in a career, the work needs to show skill, knowledge and talent. If the work is truly terrible, why would I waste my time? If the person seems lazy or complacent or complains about the difficulties or challenges of the business too much, they’re not worth my time. I only have time and energy to dedicate to one, maybe two people. If I’m making an investment in you, then you’d better show promise and prove my efforts won’t be a waste. If I think you’ve got great talent but don’t have the constitution to persevere against all odds — which this business requires — then, again, you’re not worth my time.

Tips

It really should go without saying (and as I fervently stated in last month’s Shot Craft): Have a good reel. Have a GREAT reel. Easier said than done? Not really. In this day and age, there is NO excuse for not having a great reel. Go out and shoot. If you are an aspiring cinematographer and you don’t have a reel yet, stop reading this NOW and go out and shoot. Use your phone. Borrow a camera. GO SHOOT. Get friends together and use them as actors. Or find a local community theater or college with acting classes and recruit actors to be in small scenes. Shoot a 1-minute scene, and BOOM, you’ve got reel material. Make it good. If you don’t know lighting or camera or editing, LEARN IT. Then shoot to learn more.

You need to be at a point in your career where you are knowledgeable enough, experienced enough and talented enough to merit a mentor taking you on. If you are not at that stage yet, you’re not going to get a mentor. You need to put in the work first. Get out there and learn the trade. Get out there and build a reel. Show the individual that you’re driven, you’ve put in the effort and time, and you’re looking to get to the next level. All professionals appreciate someone who is dedicated, serious, and has done their due diligence. There are some wonderful resources online, forums where you can interact with professionals all around the world. But even within those groups, individuals who come in with “basic” questions that can be easily answered with a quick Google search gain no respect (and are often even ostracized).

This doesn’t mean you’re required to go to film school — although if you go to the same school your would-be mentor attended, that can be a great personal connection. Whether you attended formal school, enrolled in multiple programs or workshops, or are just self-taught, you have to be knowledgeable to gain respect. Know your trade and be able to show, clearly, your skills and knowledge.

The mentor needs to know you’re willing to learn.

All of these points are requirements, but this one is a biggie. I have spent a lot of time with individuals over the years, offering myself as a resource. I have, many times, offered my contact information and extended the open invitation to email me or contact me on social media with any questions. Very few ever have. If they do, it’s usually one question, and then they move on. The ones who catch my eye are the ones who come with legitimate, knowledgeable questions (showing me they’ve done their work and are looking to gain a deeper understanding of something). They’re not pests, they don’t demand my time, and they’re respectful of my schedule and workload. But the ones who return get my attention.

It’s also important that they listen and take my advice/suggestions into consideration. There are many egos in this industry, and many young filmmakers want to prove they know what they’re doing, so they shut themselves off to other insights. “Eh, I know that stuff, I don’t need to ask about it ...” Or they fear that if they DO ask, they’ll be seen as weak.

If you are an aspiring cinematographer and you approach me at an event and ask me to explain an f-stop, I may patiently answer your question (most likely will), but I will not take you seriously as a professional. That’s a basic question, and the answer is easily found in hundreds of sources. If, instead, you approach me at the event and ask, “Do you think it’s a problem that we don’t have f-stop markings on lenses anymore when it’s really the f-stop that dictates depth of field and the T-stop is merely a measurement of light? Aren’t we asking for trouble in the age of larger sensors and longer, faster lenses to not know the actual f-stop?” THAT is an informed question that shows me you have a solid grasp of the subject and you’re looking for further understanding. NOW you have my attention, and you stand out. Not to denigrate anyone who asks questions — there truly are no stupid questions (except those that go unasked), and I’m happy to answer most any question I can — but asking simple questions will not inspire someone to mentor you. Seeking more in-depth knowledge might.

Further, if someone offers you advice or invites you to contact them to ask questions, DO IT. Follow up. Keep that contact alive. No one is going to extend this offer without meaning it. And no one is going to blanket-extend an offer of further contact without authentically being willing to spend their time responding. I’ve made this mistake many times in my career — I’ve had the opportunity to connect with someone at a higher point in their career, and I’ve shied away from it, not wanting to “bother” them. Phooey. If they make the offer, take it. Show your willingness to accept their advice and knowledge.

You have to be likable

This circles back to my first point, but it’s important enough to reiterate and separate into its own category. Some personalities just don’t mesh with mine. That doesn’t necessarily mean there’s anything wrong with them (or me); we just don’t jibe. I’m never going to mentor those individuals. Without that personal connection, I’m not going to spend my time. I’ll be happy to answer questions at an event or through social media, but they won’t get my special attention. If you’re a jerk, obnoxious, overly aggressive — forget it.

If I’m put off by you at all, there’s no way I’m going to mentor you (and I probably wouldn’t hire you, either).

Tips

Be personable. Be professional. Don’t be a sycophant. You may be excited to talk to the individual, but keep it under control. Be respectful of other conversations happening (if you’re at an event). Be conscious of the individual’s body language. Are they trying to leave the event and you’re stopping them? ASK them if they would mind a question first.

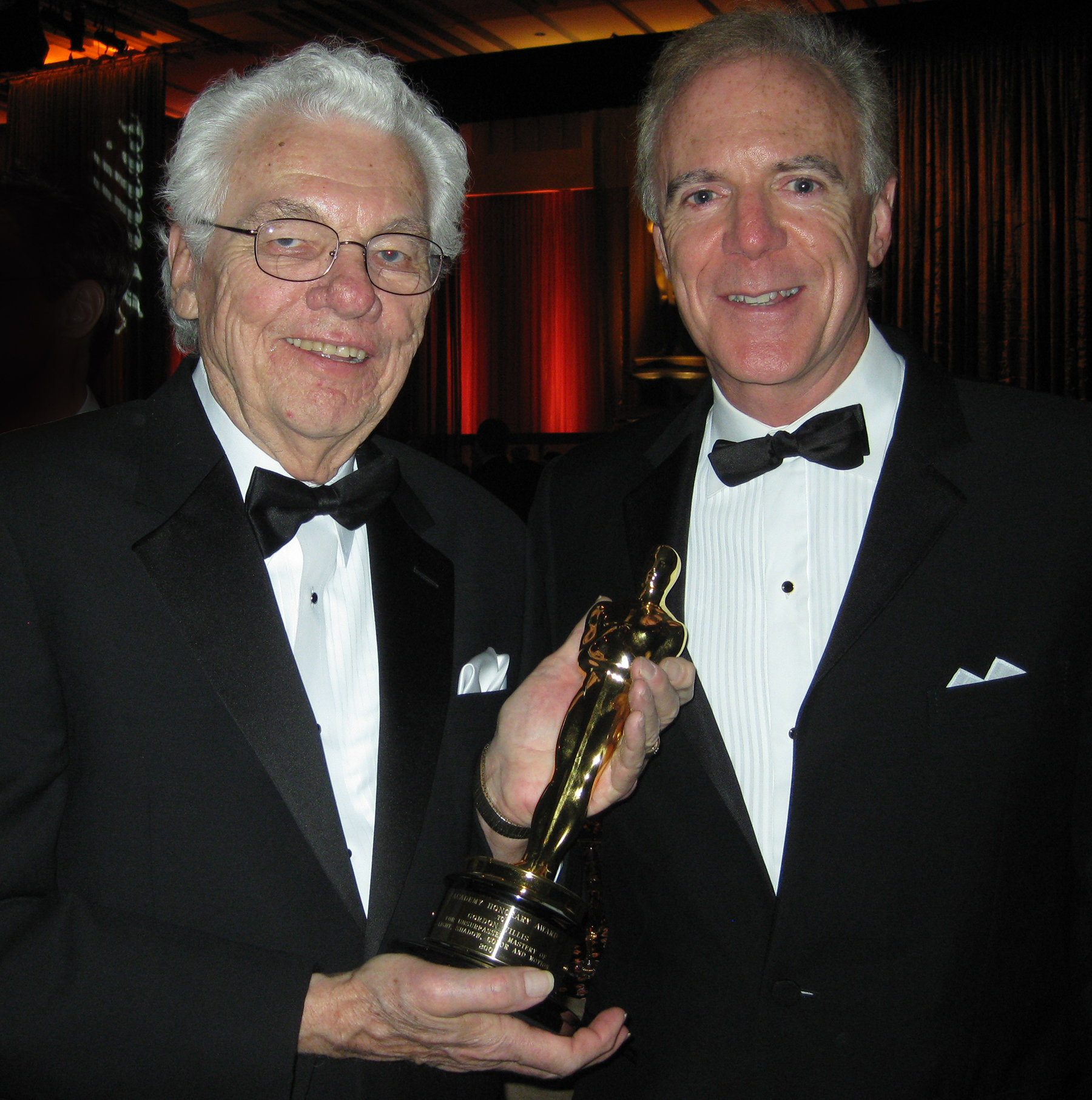

An official opportunity

Recently, through an initiative put forth by the ASC’s Vision Committee, the Society has introduced the official Mentorship Program, where individuals from around the world can apply to be paired up with an ASC member who has volunteered to mentor. The initial connection is limited to two in-person meetings or phone calls, out of respect for the member’s time and workload, but many times interpersonal relationships form and the mentor/mentee kinship expands beyond the initial connection. (Future opportunities to participate in this program will be announced on the ASC's site.)

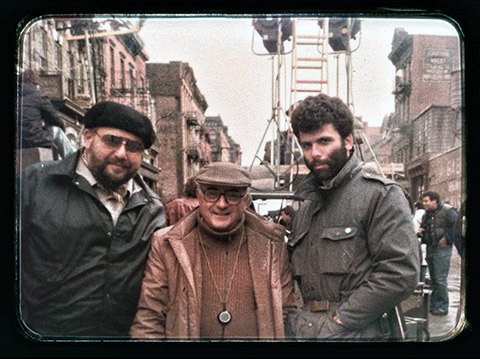

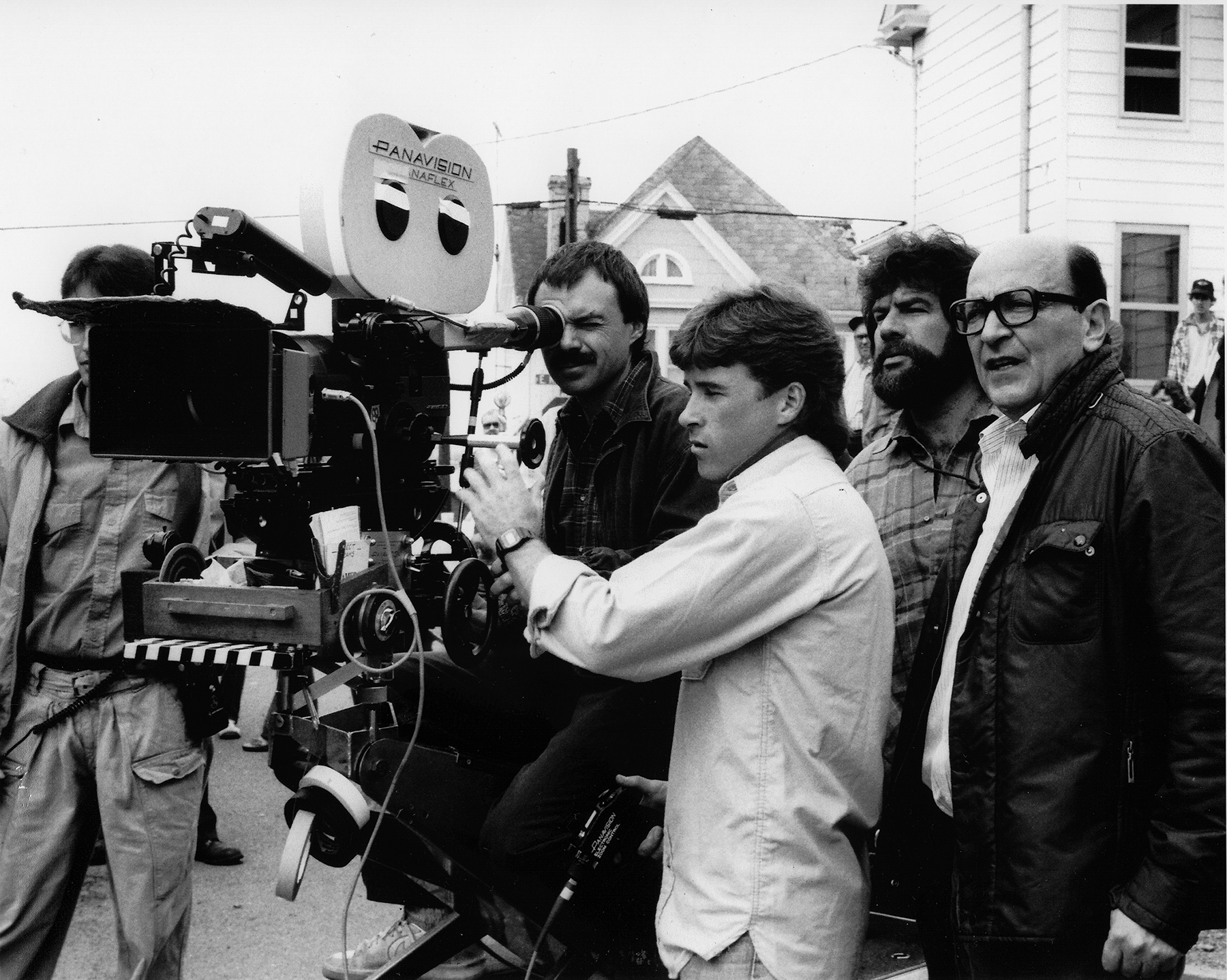

From the AC Archive

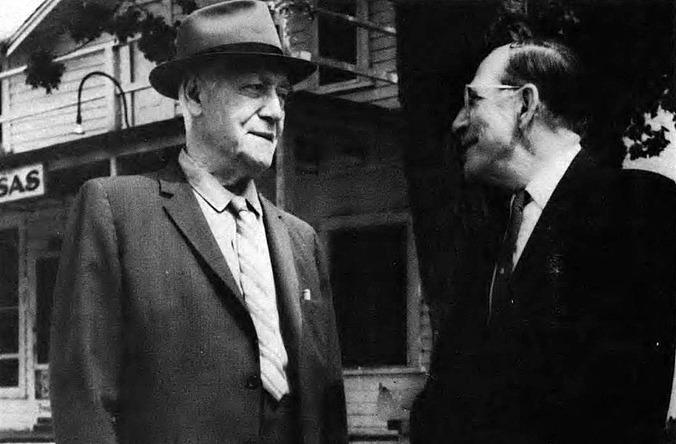

While looking through American Cinematographer issues from the 1960s, I came across this small blurb in a memorial published in September of 1969 for a late member and was touched by a note about his mentoring of a crucial member in the Society’s past.

Many ASC members have mentored those who would later become members of the Society. Most members of the ASC are extremely generous individuals who are openly willing to share their knowledge and experience with other cinematographers and students. It is truly a time-honored part of the business.

In Memoriam

Fred J. Balshofer, ASC

1877-1969

The membership of the American Society of Cinematographers is bereaved to hear of the recent death of its beloved honorary member Fred J. Balshofer, ASC. One of the few remaining true pioneers of the motion-picture industry, Balshofer was made an Honorary Member of ASC in 1965, joining a select group which has included only ten others — among them Thomas Alva Edison, George Eastman and George A. Mitchell, inventor of the Mitchell camera...

Countless cameramen began their careers in cinematography under the tutelage of Fred J. Balshofer.

Perhaps the most famous of his protégés is Arthur C. Miller, ASC, who, as a local lad of 14, was hired by Balshofer in 1908 when he founded the Crescent Film Company in Brooklyn.

He trained Miller to develop his film in the laboratory and to crank a moving-picture camera. So well did Balshofer teach Miller, and so eagerly did the teen-age apprentice do his “homework,” that he became a full-fledged cinematographer on the classic Perils of Pauline serial by the time he was 18.

In later years, Miller, having been awarded seven Academy nominations and three Oscars for his achievements in cinematography, never failed to give full credit to Balshofer for having been his mentor and guide in the learning of his craft.

You can read the entire tribute in PDF form here.

Jay Holben is an ASC associate member and AC’s technical editor.

You’ll find all Shot Craft posts here.