A Closer Look at Close-Up Attachments

Expanding upon the practical use of close-up adapters, commonly — although incorrectly — known as diopters.

In a recent Shot Craft post, we examined close-up adapters, which are more commonly — although incorrectly, as noted in that earlier piece — known as diopters. Since then, I had a chance to talk with veteran cinematographer Stephen H. Burum, ASC, who has long been a fervent fan of diopters — especially the split-field variety — and famously used them on such features as The Untouchables, The War of the Roses, Hoffa, Carlito’s Way and Snake Eyes. Burum shared a number of important points that weren’t included in the original piece; this month’s column can therefore serve as an addendum to that story and as further exploration of these fantastic optical tools.

Split-field close-up attachments come in many different shapes and sizes. The most common is the half split, where half of the filter frame is open and the other half is a close-up adapter. But they can also come in strips — horizontal or vertical — where a sliver of diopter is positioned somewhere in the middle of the frame, and the rest is open. Vantage Film, for instance, offers sets of strip diopters that come in 15mm and 30mm strip widths and +0.5, +1, +1.5 strengths. Such strips allow for finer positioning of the close-up effect within the frame as well as the ability to place more than one strip into a frame, thereby creating more than two planes of focus within a single image. There are also “slot” diopters where the filter covers most of the frame but has a small slot cut into it — the opposite of a strip. Tiffen, for example, refers to these as Letterbox diopters.

For a moment in Hoffa — directed by and co-starring Danny DeVito — Burum effectively created his own “letterbox” diopter. In the scene, DeVito’s character is having a tense conversation with John C. Reilly’s in the theater wings, while Bruno Kirby can be seen in the background, entertaining an audience from the stage. To hold all three actors in focus simultaneously, the lens was focused on Kirby on the stage, while DeVito and Reilly — positioned on opposite ends of the frame — each had his own split-field diopter. (Burum received an Academy Award nomination for his work on the film.)

Some split-field diopters come in circular frames, but rectangular frames tend to be easier to accurately position in front of the lens via a geared or sliding filter tray in the matte box. In some cases, such as with Lindsey Optics’ Rota-Split diopters, the diopter is circular in a square filter tray with built-in gear wheels on the top that allow the diopter to be rotated to any degree.

At times in his work, Burum would use a “dynamic” close-up attachment, floating a diopter in or out of the frame as the camera or talent moved. In Carlito’s Way, for example, there’s a scene in which the title character (played by Al Pacino) is watching Gail (Penelope Ann Miller) on the dance floor when a waitress comes up to talk to him; Carlito’s attention is then divided between the conversation and Gail’s dance. To hold focus on both, Burum focused the lens on Miller in the background and used a split-field diopter to hold the waitress in close focus; then, as the conversation with the waitress ended, Burum zoomed in on Miller, and as the field of view moved past the waitress, the 1st AC pulled the diopter out of the matte box to clear it from the shot. To guide this transition, a spot was marked on the zoom ring of the lens, denoting the focal length at which the diopter pull should happen.

Burum had also used the technique in The Untouchables, for a scene in which Al Capone (Robert De Niro) attends an opera performance. With the use of a split-diopter, the shot holds focus on De Niro in the distant background as well as on the opera singer in close-up. As the shot zoomed in on De Niro, the diopter was slipped out of the matte box.

The thickness of the close-up attachment’s glass often results in a thicker than usual frame. In rectangular form, in a matte box, this often means that the diopter will take up the space of two filter trays. Vantage offers +0.8 Slender diopters crafted with Ohara S-LAH51 glass; these only take up one filter tray in the matte box.

There are also circular diopters referred to as “donuts.” A donut has either a magnifying circular portion surrounded by flat glass, or a hole cut into magnifying glass so that the cut-out circular portion of the diopter offers no effect while the surrounding edges are magnified. The latter version is essentially the same as a split-field diopter, but the open area is circular in shape.

It’s important that we clear up a common misconception surrounding diopters: They do not alter the depth of field of your shot. They do not magically alter the laws of physics to give your optics an otherwise unachievable reduction in depth of field. What they do is alter the focal length of your lens, increasing magnification and decreasing field of view. There is a slight reduction in depth of field that can be discerned by blowing up an image and scrutinizing it — this is because adding the diopter changes the overall focal length of the system — but at this close-focus distance the difference is, in all practical terms, imperceptible and is not something that will affect your shot in any discernible way.

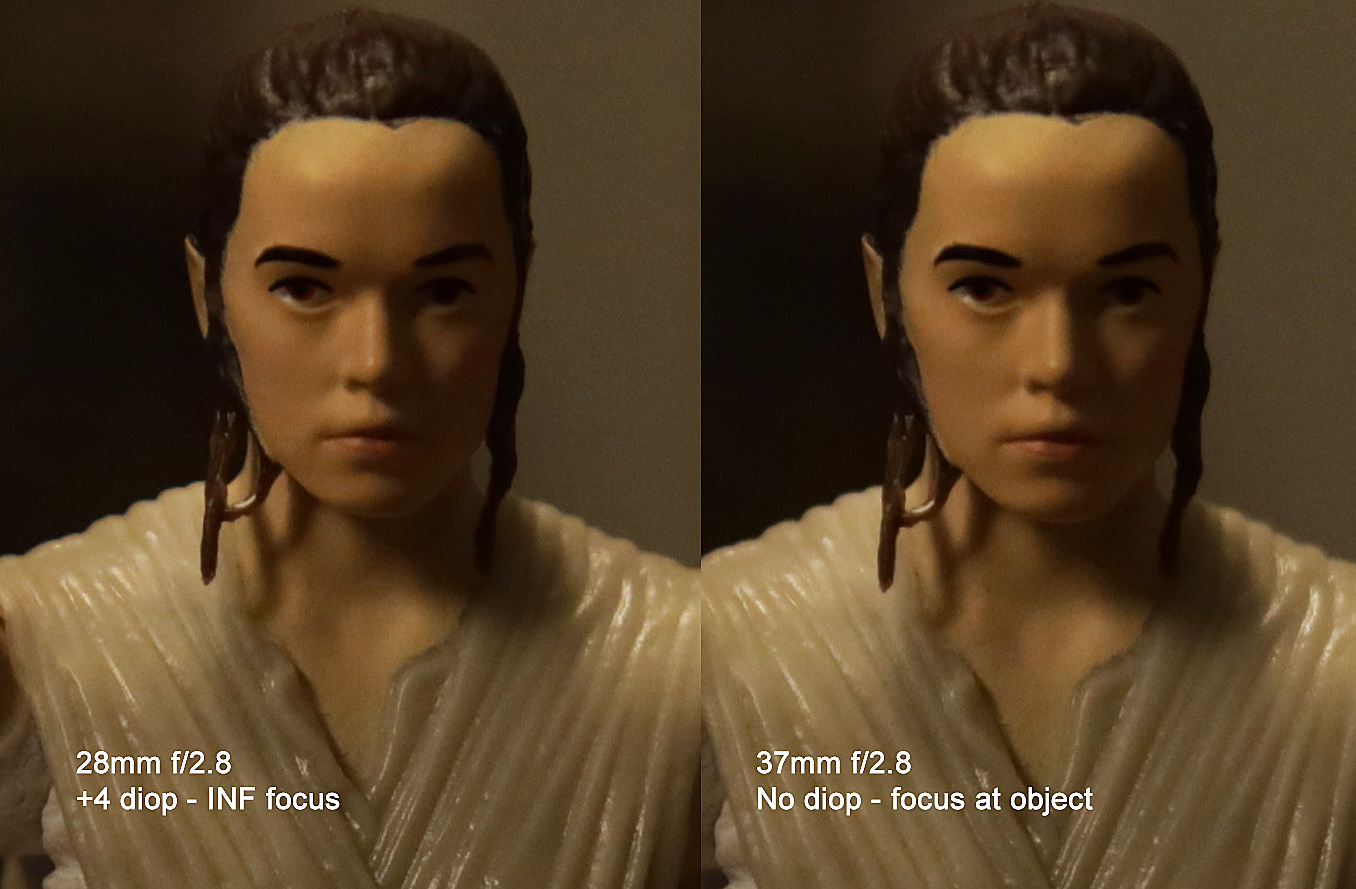

In the top comparison above, I photographed a Star Wars “Rey” action figure with a zoom lens set to 28mm, and a +4 diopter at f/2.8, and then, with the distance between camera and subject exactly the same, I removed the diopter and zoomed in — to 37mm — to match the field of view I’d had with the diopter. As you can see, there is no discernible difference in depth of field.

In the second example, I photographed Rey with a 75mm lens and a +7 diopter (+3 and +4 combined together) at f/2.8. I then removed both diopters and photographed Rey from the same physical distance to the camera. Because the field of view without the diopters was considerably wider, I had to blow up the non-diopter image by 200 percent in post to match the subject size. In this case, yes, there is a considerable difference in depth of field — but also a big difference in field of view and magnification. When comparing apples to apples — i.e., zooming in and matching field of view, subject size and distance from lens to subject — there is no difference in depth of field between a clean lens and one with a diopter.

Split diopters do affect depth of field, but that is only because they create a second distinct plane of focus with its own depth of field, so that there is a depth of field for the clean portion of the lens and a depth of field for the portion altered by the diopter. However, both of these focal planes follow the laws of optical physics. Sorry, there’s still no magic happening.

Whatever their shape and size, split diopters are a fantastic tool for introducing multiple planes of sharp focus in your image and achieving some very creative effects. I’ve even used multiple split-field diopters not to place close objects in focus, but rather to introduce large areas of soft focus!

Quick Tips

• With all split- and strip-field diopters, the cut edge of exposed glass is prone to catching stray light as it sits in front of the lens, potentially introducing odd flares or other unwanted highlights into the image. Some of this stray light can be cut simply with the matte box and hard mattes, but often a light source that is in-frame will reflect off of the diopter edge. To combat this, if you own your diopters, you can blacken the cut edge with a coating (or two) of flat-black model paint; alternatively, if you’re renting your attachments or you only want to temporarily eliminate a reflection, you can use a thin strip of photo-black paper tape to black out the edge of the glass. For best results with the latter technique, use a very sharp razor blade to trim the tape exactly to the measurement of the area you need to cover so that the tape is only on the single edge plane and doesn’t introduce any other unintended artifacts by creeping around the edge of the diopter and into your shot.

• Strictly speaking, when physically measuring focus distance to your subject you should always take the measurement from the entrance-pupil position of the lens. Unfortunately, that position is not always known, and it can move within a lens based on focal distance and zoom setting — hence the common practice of always measuring to the camera’s focal plane, a fixed position that doesn’t change. In most typical working distances, the few inches of difference between the focal plane and entrance pupil have no effect on the resulting sharp-focused subject. When working in extreme close-focus situations, however, those few inches can make a difference in whether or not your subject is in focus.

When using diopters, the entrance pupil is magnified and, effectively, advanced forward beyond its natural position in the taking lens. The common practice, therefore, is to take your focus measurements from the diopter itself at the front of the lens, not the focal plane. While this is still somewhat of a cheat, it works most of the time. But always double check with eye focus and a high-resolution monitor — and if you’re shooting film without the benefit of a high-resolution video tap, test, test, test before you shoot to determine the appropriate revised entrance-pupil position from which to measure in each situation.

“It’s important to do a series of tests with the lenses that you’re going to be working with,” Stephen H. Burum, ASC advises. He encourages focus pullers to make their own charts with details specific to the lenses actually being used. “Every brand of lens is a different physical length, so the chart has to be specific to the lenses that you’re using.” He also cautions that “if the diopter is in a matte box, it won’t be as close [to the lens] as a diopter that screws onto the lens.”

For a full “Plus Diopter Lenses Focus Conversion Table,” refer to the American Cinematographer Manual (page 752 in the Ninth Edition, or page 818 in the 10th).