Documentaries Are Stranger Than Fiction

With the “creative non-fiction” of documentaries to light the way, telling us stories about ourselves, some that may be hard to watch, we learn so much about our world, and how to live in it together.

This December issue of AC is devoted to documentaries — “creative non-fiction,” as film critic Richard Brody described them in a recent issue of The New Yorker. Many ASC members have shot or directed documentaries at some point in their lives, and some of our members have had big documentary careers: Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC (a string of BBC documentaries), Joan Churchill, ASC (Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer), Buddy Squires, ASC (most of Ken Burns’ documentaries, including The Vietnam War), Ellen Kuras, ASC (who won an Emmy for Jane), and one of our newest members, Shana Hagan, ASC

(63 Up).

Documentaries are called “fact-based,” but of course there is a wide array of documentary genres: interview films, performance films, historical summaries, biographies. They may all purport to “document” the facts, but invariably some hew closer to the facts than others, depending on the filmmaker’s choices.

The earliest cinéma vérité documentaries in this country, shot with hot-rodded Auricons, like Primary (1960), were true “fly-on-the-wall films.” The Maysles brothers made such films, like Salesman and Grey Gardens, but these films ran up against the passions of the ’60s, when audiences sought films that leaned more into the issues of the day: civil rights, the war in Vietnam, political conflict.

And so documentaries like Hearts and Minds, Peter Davis’ 1974 film critiquing the Vietnam War, were made. I think of them as essays, using reality and interviews to distill some truth out of conflict. We find ourselves in a similar place today, in the fading light of 2020, in deep conflict. Documentaries like Hillary (2020) perhaps lean too far in one direction, because the subject — Hillary Clinton — allowed access to her campaign and was granted an editorial role… so was it a documentary or sponsored film? Sometimes with docs it is hard to know… we may think we can weed out fact from fiction, but we often can’t. All documentaries are a selective view of the world: what is included, what is excluded, what angles things are seen from, or not seen.

One hopes the current generation, which was brought up on posing for selfies, will make documentaries that include their voices, where they’re coming from, their points of view, because documentaries are most powerful when we learn to trust the filmmakers by knowing their POV or bias.

Honeyland fits that bill. It was the first winner of the new Documentaries category at the annual ASC Awards last January, with cinematographers Fejmi Daut and Samir Ljuma earning the prize. A heartfelt film, with the main character in almost every scene, it transported you effortlessly to Macedonia and made you believe in that world as presented.

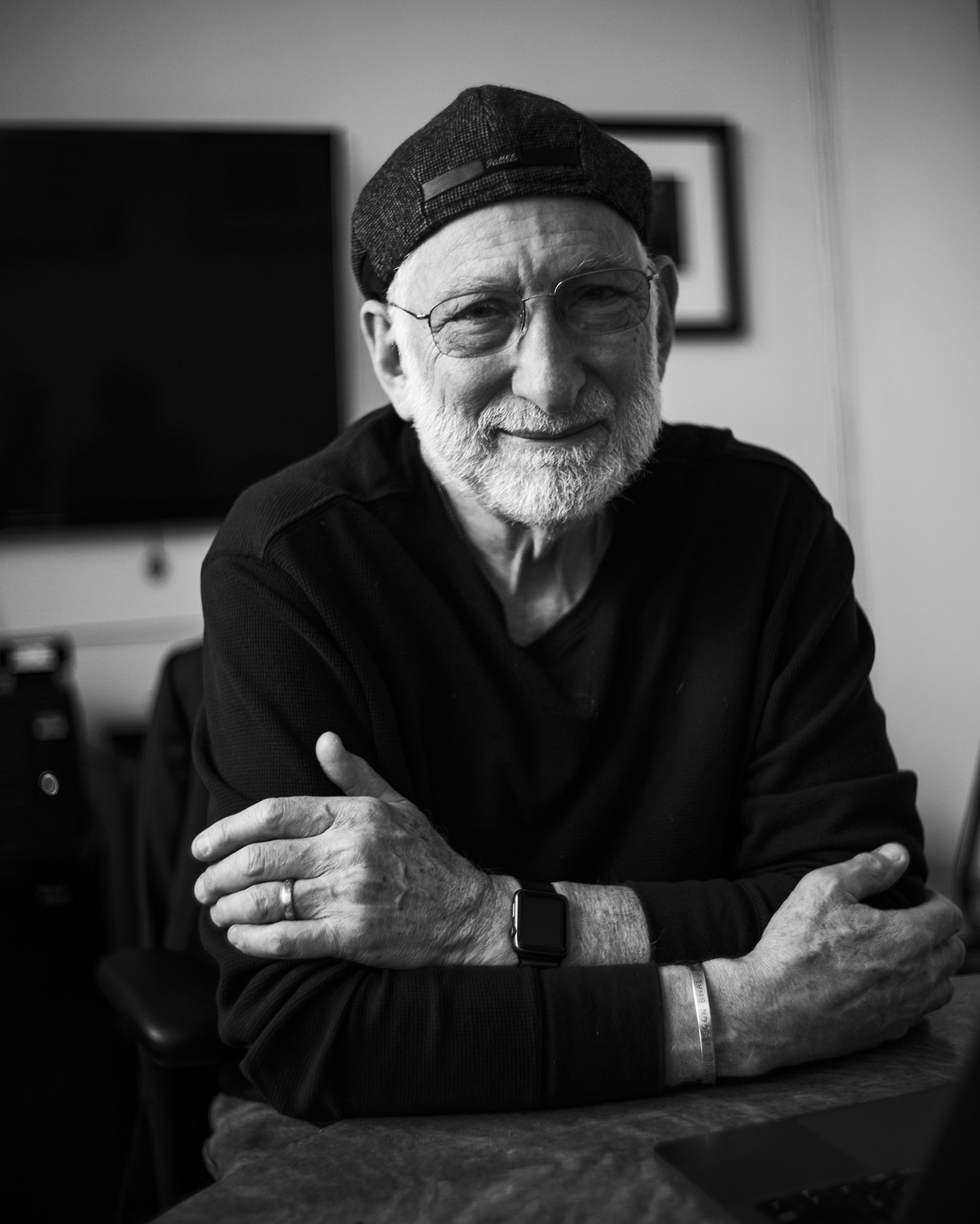

This month of December 2020 (a year I will be happy to celebrate the end of…) marks the 51st anniversary of a documentary I worked on early in my career, which remains indelible to me as an experience and also as a finished film, and represents the contradictions and confusions I have mentioned above. That film is Gimme Shelter (seen at top of this page). It began as a sponsored film (to document a Rolling Stones concert tour), became a documentary as Al and

David Maysles wanted to document the band on and also off the stage (and so filmed a memorable scene of the band mixing the tour record at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio), went back to being a performance film as the band appeared at a free concert at a stock-car track outside San Francisco, and then back into documentary mode as the concert descended into violence and chaos, and 18-year-old

Meredith Hunter was stabbed to death in front of the stage. My role was on-stage cinematographer throughout the December 1969 concert at Altamont Speedway. I saw and filmed the chaos first-hand — it was hard to watch.

In the decade that followed, the divisions in our country became ever more profound, due to the war in Vietnam, but also due to the self-immolation of President Richard Nixon and his Watergate scandal.

The more things change, the more they stay the same. America always recovers from its darkest days. With the “creative non-fiction” of documentaries to light the way, telling us stories about ourselves, some that may be hard to watch, we learn so much about our world, and how to live in it together.

Stephen Lighthill

President, ASC