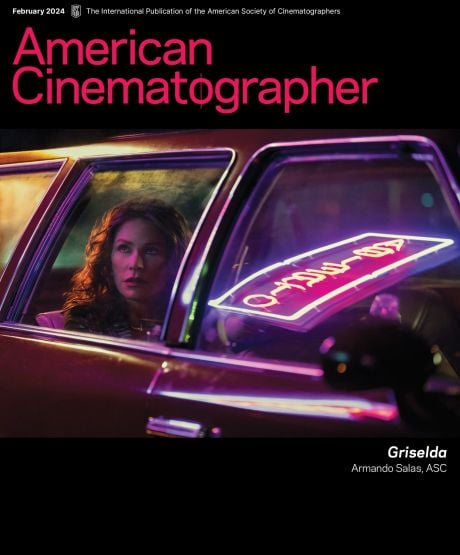

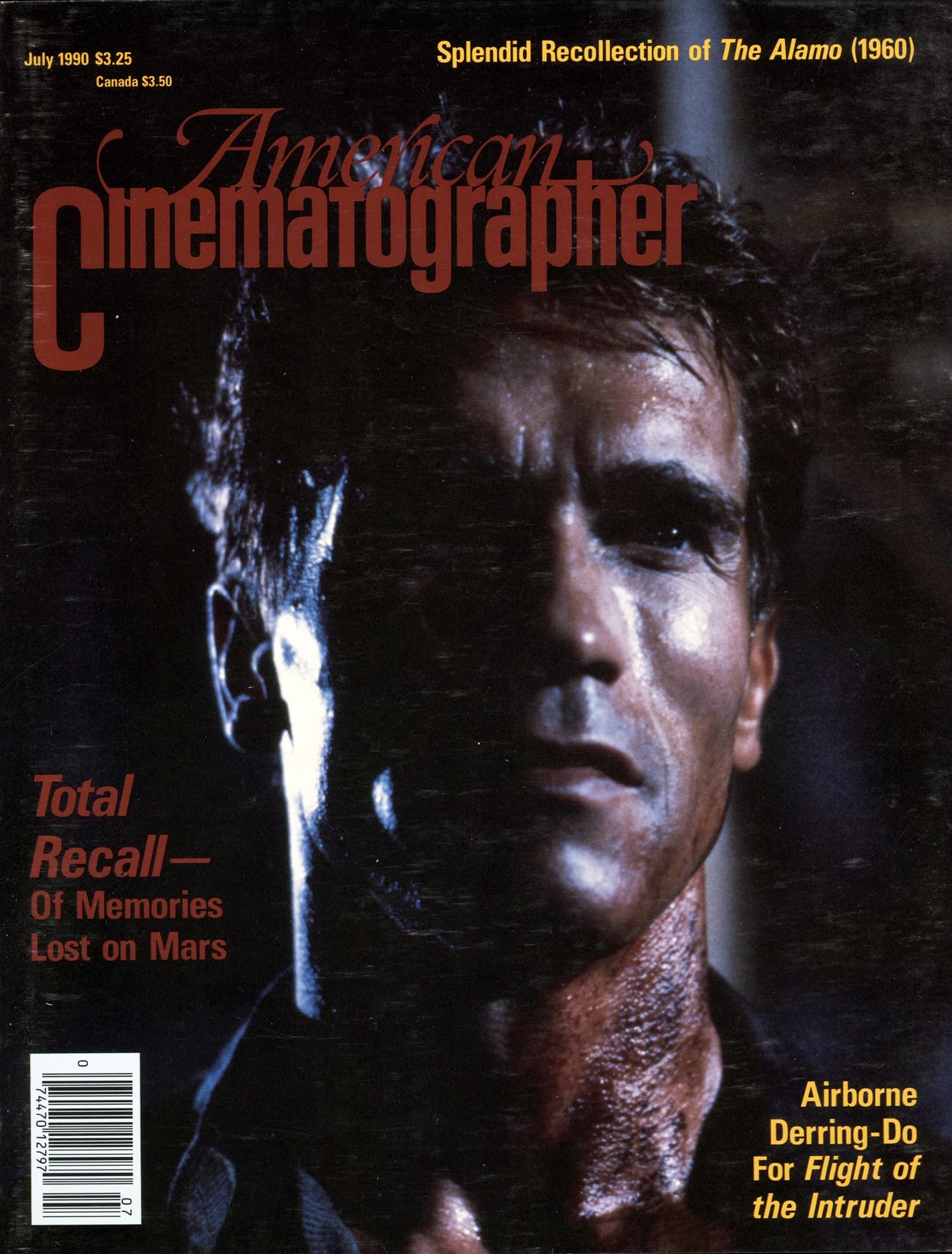

Total Recall: Interplanetary Thriller

Director of photography Jost Vacano talks about shooting in Mexico and creating that “Martian Red” look for this sci-fi action thriller.

By Nora Lee

Unit photography by David James, David Appleby, David Capistran & Merrick Morton

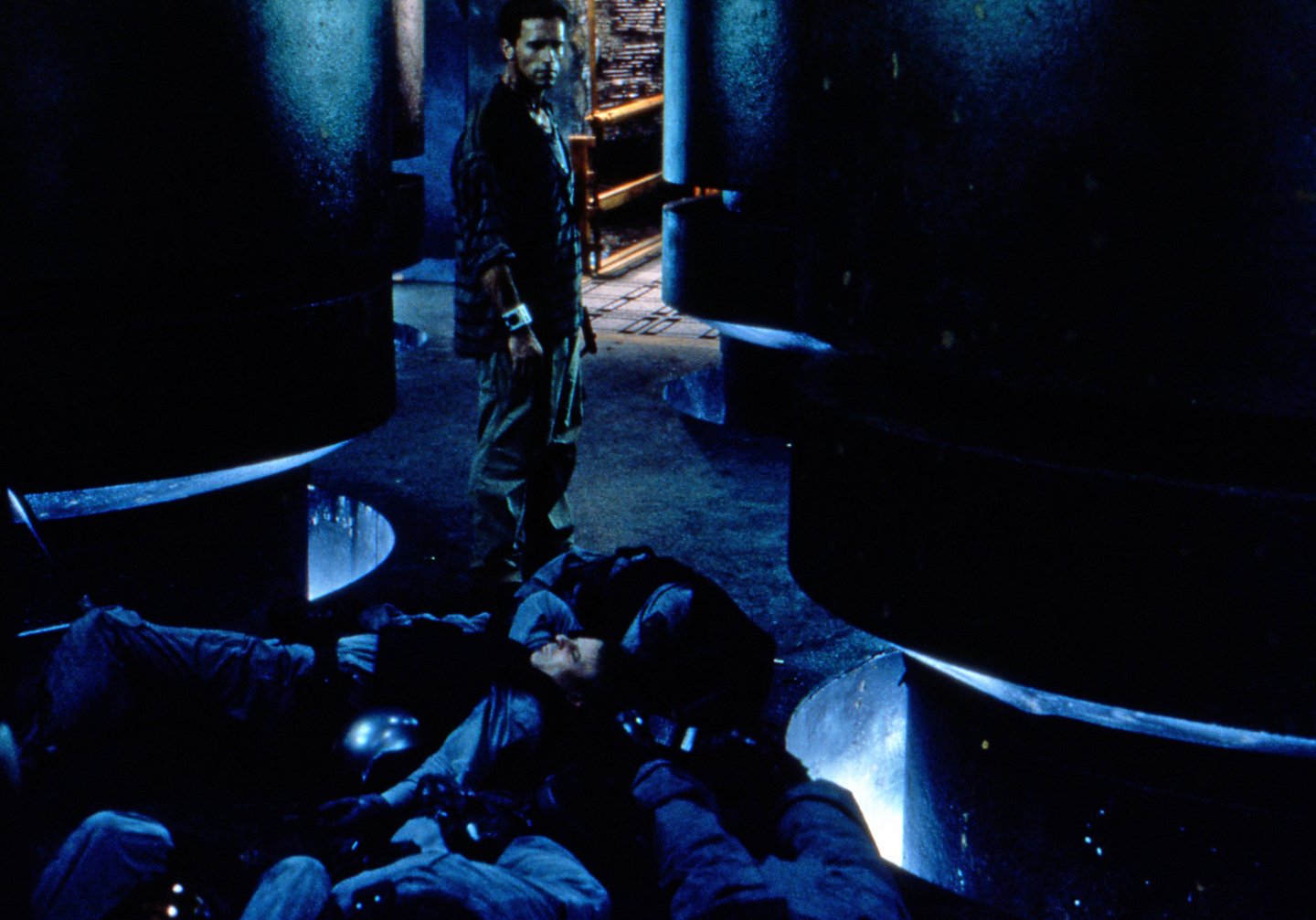

The street set at Churubusco Studio in Mexico City is highly reminiscent of an old Western mining town except it is filled with a strange red-orange light. Extras are milling around waiting for their brief walk-through. Rob Bottin's make-up artists are fussing over the mutants they've created — applying a little more red here and smoothing a seam there. The Martian taxi is in position and so are three cameras. When assistant director Kuki Lopez calls for quiet (in two languages) and director Paul Verhoeven calls for action, cinematographer Jost Vacano and his crew begin recording Arnold Schwarzenegger's first moments in Venusville, Mars. Welcome to Total Recall.

Total Recall is a big picture. The last budget estimates floating around Hollywood indicate that it might well cost almost $70 million. But few people seem to think there is much risk involved. After all, Schwarzenegger is one of the biggest box office draws around. Verhoeven's last picture, RoboCop, was a smash. And everyone says the script is really good, if unbelievably ambitious. Jost (pronounced Yoast) Vacano (who also shot RoboCop) agrees, but he wasn't attracted to the project solely by the story.

"Paul Verhoeven has been one of my favorite directors for a decade or more," explains Vacano. "I started with him in 1976 or so with Soldier of Orange and it's still one of my favorite films. Then I did Spetters with him. It's very funny, he likes to work with two directors of photography, Jan DeBont (Die Hard) and me. He always does two pictures with each of us, then he switches.

"I met him by accident through a producer in Germany. Holland and Germany are very close and the mentality is very similar. The languages are alike, even a few words are the same," laughed Vacano in his soft German accent. "Paul has very good common sense and we have a great understanding of each other — our good sides and our bad sides. Total Recall was a very interesting script and we both felt that if we could get a grip on the ending, it could be a terrific film. The ending was a major challenge and it still is — like in most movies!"

The entire project was a "major challenge" from the more than 35 stage sets to the hundreds of effects shots. Vacano explains, "Normally in films like this you have long sequences that are very straightforward and then you have, as a highlight, effects scenes. This time, effects are everywhere, every time, especially for the ending. When I saw the rough cut about four months after we finished shooting, the last two reels were full of 'scene missing, scene missing, scene missing!' There was nothing there but some music!"

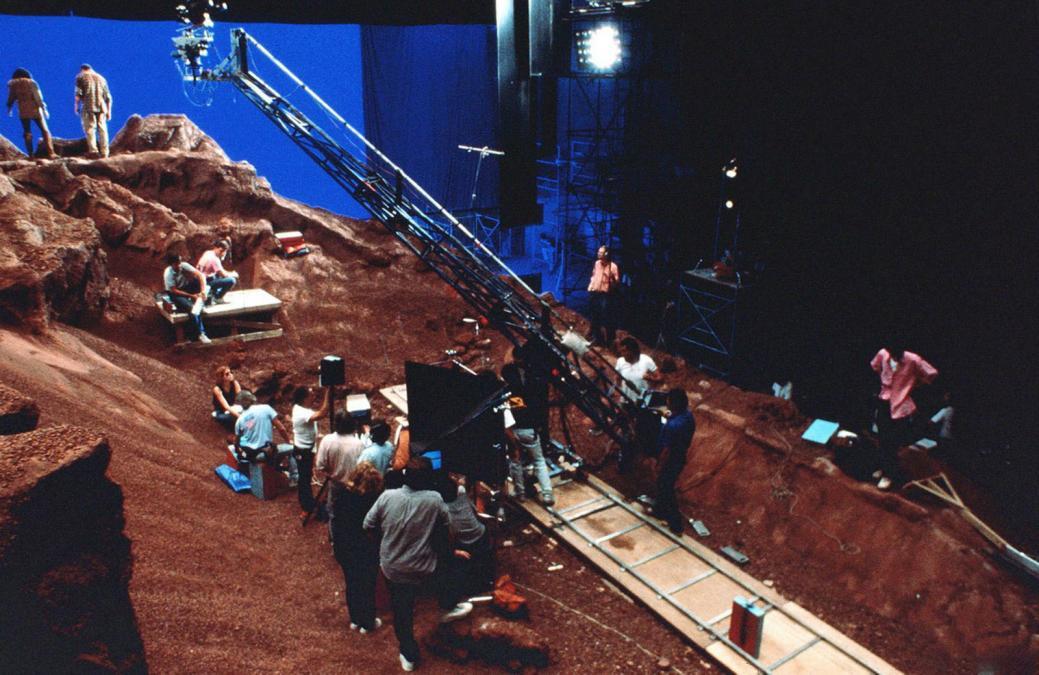

According to Vacano, the really big story of this film is the 35 sets by production designer William Sandell. Eight sound stages filled to capacity four or five different times for 3 to 5 days of shooting each time was a daunting prospect even to the man who shot Never Ending Story and Das Boot. "When you read a script the first time, you don't pay so much attention to the sets. But when you've read it many times, it occurs to you, all this must be happening in a huge place! It's like a city! And it's on Mars! Where will we find a studio so big that we can build a whole city there? A closer look told us that it wasn't just one city. It was a lot of large areas of the colony — part city, part mine, whatever.

"We had a schedule of 80 to 90 days. That meant we could expect to go to a new stage every three to five days. Of course, everyone expected that when we left one stage and moved to the next, it would be all lit and we could start shooting. This was one of the moments I almost lost my confidence."

Logistics were unbelievable. It took as much as a week and a half to rig the lighting on a stage. Sometimes it took four to six weeks to build the set and yet rarely was the first unit on a stage for more than a week. Vacano was understandably overwhelmed by the size of his task. "The question was, how do I keep a handle on these events? Pre-lighting one stage while shooting on another is what you normally do, but we had to pre-light stage A, while we were pre-rigging stage B, completing shooting on stage C and trying not to run into the second unit on stage D. We had to leave maybe two more stages up to do some special effects shots whenever we had time for them.

"That created yet another problem. The budget, no matter how big it might be, is always limited below the line. We had only so much money in it for lighting equipment. Normally you have money for a certain number of lights plus a few to get you started on a second pre-light. And that's all. It actually turned out that we had most of the stages up and in some stage of lighting most of the time. We used every single light in Mexico City and from everywhere around!”

In spite of the odds, Vacano became philosophical about his predicament. "The only way to get over these feelings is to go day by day. If it is a hundred days of shooting or three days of shooting, it is always one day of shooting. It starts in the morning and ends in the evening. And you have to get through this day and then you can concentrate on the next day."

Most of the film was shot on stage, but there were a few location exteriors. Finding locations that Verhoeven and Vacano could imagine as futuristic in the ancient town of Mexico City seemed like another insurmountable problem. "We have a science fiction film and we are looking for something that looks like the future. We think, 'Oh yeah, it has to be high, steel and glass. Immediately, I think, most Americans would arrive in Houston or a place like it, where there is some of the most modern and futuristic architecture. Paul and I knew Houston already because we had intended to do Robocop there. So we thought that is where we would go.

"But then we hear, 'Gentlemen, you have to shoot this film in Mexico because this is where we have the contracts. There is no budget to take a big crew to Houston. You have to find your futuristic world in Mexico.' We thought oh, damn. We drove around for three or four days in the city and we found nothing. We were worried. 'How can we do this if we aren't allowed to go to the only place that we think looks futuristic enough?'

"We started to notice that there were some interesting things happening in Mexican architecture. Especially the ways they use concrete. We looked a little closer and we began to think that, although it was very old-fashioned in one way, it was very futuristic in another and it wasn't steel or glass. All of a sudden we started to find really great locations. They are completely different from what everybody would expect and I think that is very good. It was a really big advantage that we were forced to find something in Mexico. It's much better, much more interesting, and it hasn't been used this way before."

The film is set in the future, but not very far into the future. The first part takes place on Earth — "an Earth we all know." But the real story unravels once Schwarzenegger returns to Mars. Mars was the challenge, but also the opportunity. As Vacano tells it, "On Mars everything is special, everything is unusual. There is no atmosphere on Mars. The people have to be either in spacesuits or in the protected colonies. This is not a picture about people in space suits. So, we imagined a colony where the miners live digging special metals out of the planet. These people must have their own environment."

Parts of the colonies are built under large glass domes. The domes provide a source for most of the light. However, much of the colony is built under the planet's surface. "This decision to build underground indicates already that whatever is on Mars is concealed," says Vacano. "The second thing that makes Mars very special is that everything is red. Even though there is no atmosphere, the surface is red, the sky is red and the sun is red, so whenever there is a connection to the exterior world on Mars, the light is all red."

Just what color is Martian red? Vacano explains that it wasn't an easy question to answer. "We had a very funny experience trying to get the gels for that red light. Every director of photography, every gaffer, has these nice little swatch books from Rosco or Lee or someone else. You go through them and say, 'This is a wonderful color.' You do a film test and it looks great. It was two weeks before shooting and I just figured we would order what we needed — two hundred or three hundred rolls — it was a huge amount. Then we found out the color we chose wasn't in production anymore. I tried to substitute with another color from another company, but the film tests didn't work. Finally, Rosco agreed to manufacture it for us and they started production of this special color again. Just barely in time we got what we needed."

Besides determining what color Martian red is, Vacano and Verhoeven decided on a "very sourcy" lighting style for Martian exteriors. "It has to have a very bright sun because there is no atmosphere to soften it. Some of the exteriors of Mars were shot in a big mining area near Mexico City which is dominated by a lot of brown and red. We used that location partly for wide exterior shots. So we had the problem of a landscape lit by a blue sky, not a red sky and the shadows were all blue. You either need a tremendous amount of red light to fill up these shadows — but that disturbs the whole atmosphere - or you can do what we did. We used the Lightflex pre-flashing device. The film is flashed with an even light through the lens. You can see the effect through the lens so you can control it by eye. The good thing is that this light can be any color you want.

"This type of flashing would be very complicated to do in the lab because you would have to flash the film with the opposite color and it is very hard to judge. But with the Lightflex, it was very easy. We used our preferred Mars red and flashed the film with that. It filled up the blue shadows with an extremely reddish light and in addition to that we used two 85 filters to help the lab a little bit. "We also used a filter that enhances all the reds without affecting the other colors. I knew this filter because I have used it in late autumn situations to enhance the color of the leaves. All of this gave us the possibility to make everything as red as we could and still have halfway normal fleshtones. If you just colorize the whole thing then the faces are as red as everything else and it's not really believable anymore. When you try to feel the emotions of the actors you don't want them to be just red cutouts."

Vacano describes many of the Martian scenes as "tricky." "At the end of the picture, for example, people are thrown out into the atmosphere and because there is no air, they are dying. We had to shoot people who were part of this exterior landscape on stage to control the special effects. Everything had to match because we cut from the exterior shots to ones done on stage and then we are outside again. Matching is one of the biggest challenges for the director of photography anyway."

Lighting was a key issue because of all the logistical problems and because of the science fiction nature of the story. Vacano overcame the scarcity of lights by having the Mexican crews build units. They made numerous Dino-type lights and they also constructed boxes to house Vacano's secret weapon — the color-balanced fluorescent.

"I've found that there are a lot of advantages to fluorescent lighting. In most of the cases you can show your light source. I always like sets the most when they are not overtly lit — the lights are part of the architecture of the set, integrated in so the set is almost totally lit by practical lighting. If this is thought of far enough in advance that you can work with the production designer, you can do it easily. Then you have a situation where you can walk into a set and switch on the lights and start shooting — almost. Directors love it.

"Another thing, because fluorescents are long, narrow tubes, they are very soft in one direction and hard in the other direction. Sometimes I like to use them for lighting women's faces. You can create a very soft look and still have a hard cutoff. It just depends on the direction you place them. This works very nicely on round faces. You can maintain a very soft unsourcy look and still have precise control on the sides.

"Sometimes it is difficult to approach actors with a fluorescent light. They say, 'What are you doing? Do you want me to look green?' You have to talk them into it. You have to explain that it's not that way anymore if the lights are properly balanced." Vacano used a new line of lights manufactured by Kino Flo, Inc. in Pacoima, Calif. He found them to be lightweight, extremely versatile, and easily controlled by using barn doors, mylar reflectors and grids.

"Kino Flo's new high frequency ballasts have no flicker problem so you can shoot at any speed and with any shutter angle that you want. You can dim these fluorescents without any color change. All other light sources change color when you dim them. It's incredible how versatile they are. If you use them in the right way, they can be high tech movie lighting equipment at a very moderate price."

The best use of fluorescents is in the reactor room. This set represents an alien reactor built in some distant past. It is filled with giant columns representing fuel rod housing and extends thousands of feet into the core of the planet. No one has been in the structure in recent memory, but the villain and the hero determine that here is where the future of the planet lies. The question, of course, is where does the light come from? "This was my question!" Vacano said and laughed.

"The stage was filled with twenty or more huge columns and everything was painted in a very, very dark green. The first thing I noticed was that the columns were standing on the floor. I got the designer to build up the floor and leave a gap around each of the columns. I filled these big gaps all around with fluorescents. Again, it's a not a sourcy light. It gives a wonderful glow and the light seemed to come from the underground glacier. That was my first approach. So my rigging gaffers started to work.

"In order to see what they were doing they brought in work lights and put them where they needed them. Then I saw it, 'Ah, this is very interesting. This very nice shiny dark color has a good reflective quality all around. This is good. This is something I can work with. We can light this so you see all these big columns just by reflection on their curved surfaces.'

"We used the fluorescents, each with eight tubes mounted in boxes four feet high, and hid them behind the columns so they would light the surrounding columns. We could stack the boxes so we had the height and we could control all these nice reflections. It seemed to continue for miles and you didn't miss the light source. This was the set that gave me the biggest problems thinking about it and it turned out to be one of the easiest sets I've lit in a long time. Suddenly I had no more nightmares, I could sleep well again." If fluorescents were Vacano's sedative, then Arriflex cameras were the caffeine he needed to keep going and get the job done. "We used so many cameras that sometimes I lost count. We had so many action scenes and scenes that were unrepeatable, that whatever camera was available, we put it somewhere. 'Oh, there's another space, can we put a camera there?"'

And why shouldn't Vacano be an Arriflex fan? "After all," he says, "you have this guy who grew up in Munich a few blocks away from the Arri factory — of course he has always shot with Arris! For many years there were no Panavison cameras available in Germany. Of course, now there are many places to rent Panavision. I'm a fan of Arri cameras because if you work all your life with a very special camera, it becomes part of you. And by the way, I own several of them."

Vacano found that there were two pieces of camera equipment that increased his ability to respond to Verhoeven's call for a moving camera — the Pee Wee and Panther dollies. Vacano had access to the new Panther dolly for a full six months in Mexico and grew to love it. "It goes up and down with a finger tip," he explains "even the camera operator can control it. Positions and speed can be preset and stored. It's smaller and more compact so it can be used in especially tight locations."

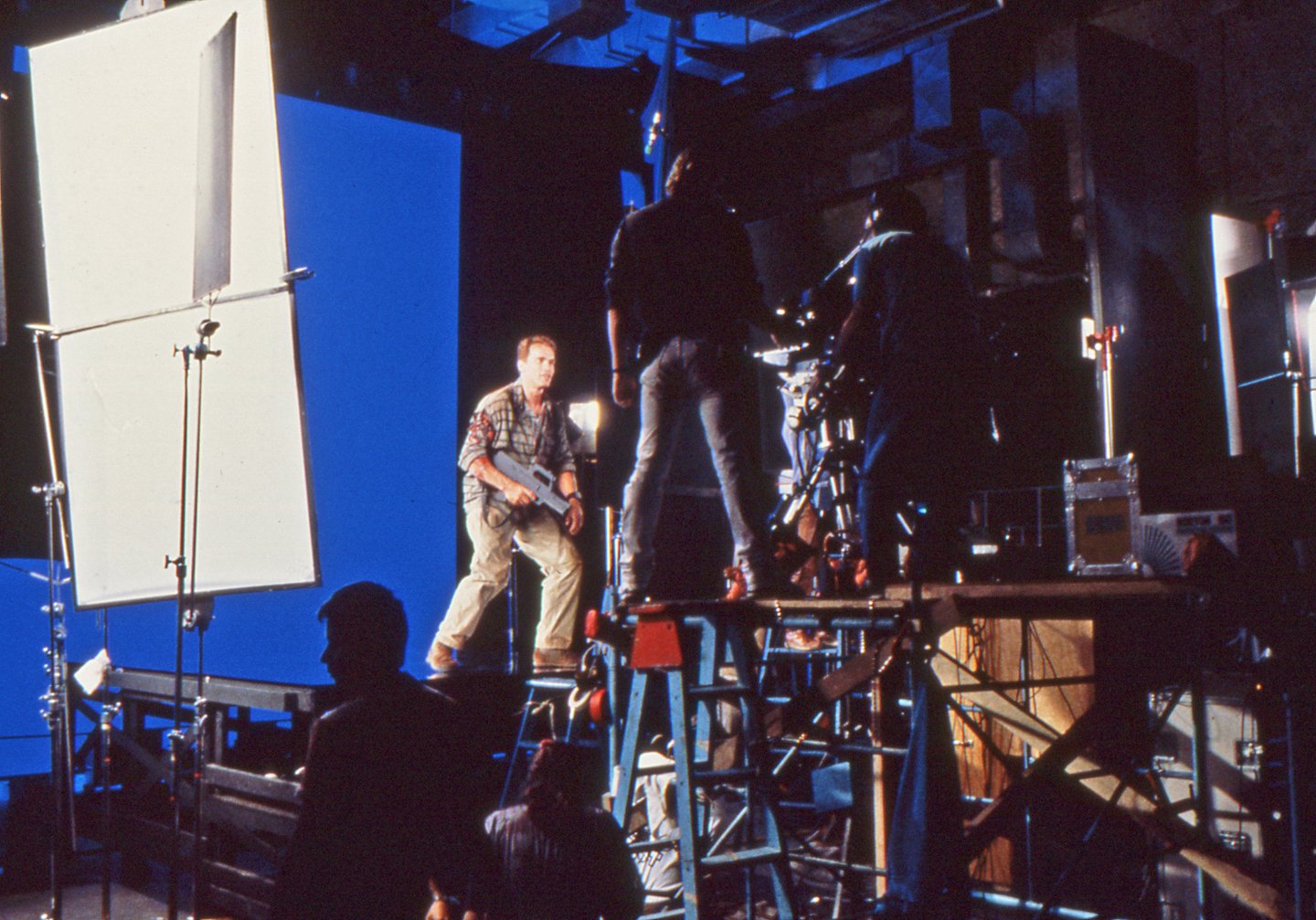

Not too surprisingly, Total Recall was shot on Kodak film-stocks. "Whenever you start thinking about a new film project," Vacano allows, "you think that maybe it would be a good time to try a new film-stock. Maybe you can get a new look for your film. But then, of course, whenever there are optical effects, even just a few effects, the optical houses insist on Eastman 5247. So the decision was very easy even though Kodak has developed the 5295 stock especially for blue screen. As it turned out there were problems with 95, so the low-speed 47 had to be used for all the effects sequences.

"It's a bit of a strange situation. The high speed stocks are so wonderful now that you can use it on interiors without compromising quality, and you can stay at very low light levels. But when we know we have an optical coming up things are going to change dramatically.

"The key to blue screen is that everything from the foreground to the background has to stay in focus or you can't pull mattes off it. Which means that you have to have much more depth of focus than you would normally. With VistaVision you need a longer focal length to get the same angle of view. And with that long lens, you have much less depth of focus. You want to have a fast stock to work with in this situation so you can stop down, but instead, you have to switch to a much slower stock. You have to compensate two stops for the slow negative, another for the longer lens, and two more to get the increased depth of focus. That's five stops altogether, which means you have to increase your normal light level by a factor of 32! On a blue screen shot you wind up putting in every light you can find space for — wherever there is a generator with a few amps left — to try and get a little depth of focus. I used 47 for complete sequences with a lot of special effects. The rest of the time, I used 95 because 96 was not available yet."

It's not surprising to find that the cameraman from Munich also prefers Zeiss lenses. Although they weren't "right up the street/' they were only 100 miles away in Stuttgart. "The Zeiss lenses are very sharp and technically very, very good," says Vacano. "Sometimes, photographically, they are a little too hard, but you can quite easily lower your contrast a little bit. On the other hand you have the contrast if you need it. Choosing lenses is partly personal taste and partly the way you are used to working.

"For instance, I mostly used low contrast filters on Total Recall. It takes the edge off a little and helps the look of the film in the dupe stage. The final prints are always on the hard side — no matter how soft you try to make it. But I'm not a filter freak. Whatever look I want to achieve, I first try to do it with the lighting."

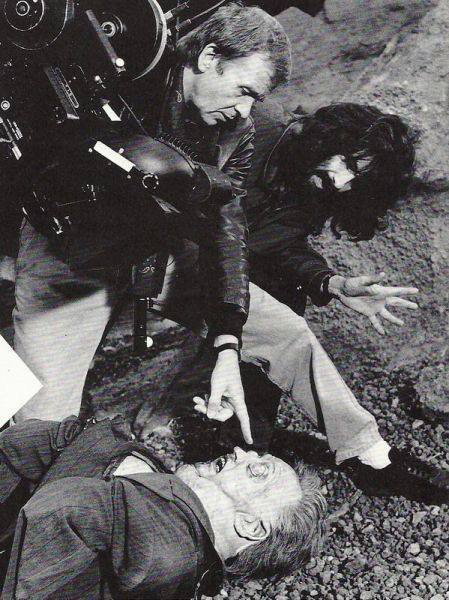

Total Recall was in production for over a year. Vacano and the first unit were in Mexico some eight months doing principal photography, second unit photography and blue-screen. So add one more to list of challenges for Vacano: "Budget considerations dictated that I use a Mexican camera crew. The only crew member I brought with me was my operator, Anette Haellmigk. The Mexicans all proved to be very good technicians. But I was concerned who would be with me on second unit? I was not used to working with a second unit in Germany. I was very lucky to have Alex Phillips [ASC], who lives in Mexico City. To find somebody with whom you can really collaborate is wonderful. He's such a great cameraman, I was very reluctant to ask him to do second unit. 'It's impossible,' I thought.

"But we talked and he told me that he was the father of a new son and he had been out of town for most of the last three years. In fact, he shot a miniseries in Germany while I was shooting in America. He felt he was very lucky to have an opportunity to stay at home with his family. He seemed so happy when I finally asked him to do second unit! We became very close friends." Vacano was also very concerned that he keep his eye on the effects work. He was aware throughout shooting that how he did his work would make it either very simple or very difficult for the miniature photography crew and the blue screen crew. He was always on hand in Mexico when Eric Brevig, Rexford Metz, ASC and the Dream Quest Images crew were filming either background plates or blue-screen. "There may be another crew preparing it and even shooting it, but in the beginning I am there to discuss what should be done. My gaffers are there to help light and I am always looking over what the blue-screen crew is doing. Anytime blue screen is shot, I have checked it and made my final corrections to the lighting. This will help later in trying to match footage.

"I wasn't around as much as I would have liked for some of the effects and miniature work that was shot in Los Angeles. That is one of the disadvantages of living somewhere else. The good thing, of course, is that I am so close with Paul. He understands a lot about photography and he knows exactly what we did and the way that I would like to have it. He watches it very carefully."

Total Recall was a very involving project. It asked much of the crew and the cast. There were moments on the set when everyone cheered and there were moments when everyone thought that Total Recall was the never ending story. In retrospect, however, Vacano insists that he has no favorite shots: "When I see the film I try to get involved with the picture the way an audience would. I try to feel what emotions are coming over me. I don't look at the shots and I don't look at the lighting. I don't think 'I did that well' or 'I did that badly.' I just try to get a feeling of whether or not the movie works. I think that's really the only thing that counts."

You'll find our complete story on the film's visual effects here and the innovative CGI "x-ray" sequence here.

Following the production of Total Recall, Jost Vacano was invited to join the ASC. He collaborated again with director Verhoeven on the features Starship Troopers, Showgirls and Hollow Man.

AC Archive subscribers can access this entire issue, as well as more than 1,200 others. Subscribe here.