Star Wars: The Last Jedi — Designing Whole Worlds

Production designer Rick Heinrichs discusses his experiences in taking Star Wars: The Last Jedi from concept to screen.

Production designer Rick Heinrichs discusses his experiences in taking Star Wars: The Last Jedi from concept to screen.

By Noah Kadner

Unit photography by Jules Heath, John Wilson, Jonathan Olley and David James, SMPSP, courtesy of Lucasfilm Ltd.

Rick Heinrichs is a veteran production designer whose credits span a multitude of genres. He made an early career connection as a designer and sculptor on Tim Burton’s first studio project, the short film Vincent, and he’s since worked with the visionary director on projects ranging from Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, Beetlejuice and Edward Scissorhands, to Sleepy Hollow, Big Eyes and the upcoming Dumbo. Heinrichs’ diverse credits also include The Fisher King with director Terry Gilliam, Fargo and The Big Lebowski with the Coen Brothers, and the Pirates of the Caribbean features Dead Man’s Chest and At World’s End with Gore Verbinski.

In realizing the environments of Star Wars: The Last Jedi, Heinrichs worked closely with writer-director Rian Johnson and cinematographer Steve Yedlin, ASC. AC caught up with the production designer over the phone in the weeks leading up to the opening of The Last Jedi.

[Editor’s Note: AC’s full coverage on The Last Jedi will appear in our February issue.]

American Cinematographer: How did you come to work on The Last Jedi?

Rick Heinrichs: I was contacted by Rian Johnson and producer Ram Bergman in the late summer of 2014. I'd never met them before, but I assume that from the work I've done they thought this was something I could do. I was familiar with Rian's work on Looper [AC Oct. ’12] and The Brothers Bloom, and I was amazed that he was stepping up to such a massive project. What's great about Rian is he's a very low-key guy in many respects, but there’s definitely something going on under the hood. He pitched me his idea, and three years later it seems like the finished film is almost exactly what he pitched me.

Did the previous Star Wars films provide an overall guiding aesthetic for you to follow?

Heinrichs: At the time [I started], The Force Awakens [AC Feb. ’16] hadn’t been released yet, so I didn’t quite have any context for this new trilogy. But there's a visual language in the Star Wars films that really arises from George Lucas' initial take: science fiction, Western [and] opera, with a documentary style of capturing the drama and characters. It's very important that you stick with that instead of standing in awe of the really beautiful visuals. That initial simplicity has allowed the design to feel very organic to the story.

In the original trilogy, Lucas was after amazing-looking locations on Earth, more so than in the prequels, which ended up being a bit more fantastical. Certainly in [Episodes] IV, V and VI, he went to real locations to shoot real objects and amazing landscapes in real light. It was taken for granted that's what we were also going to be doing with these new movies.

How would you determine what would be built on location versus on stage — or with visual effects?

Heinrichs: It's very much a process. The initial mandate from Rian was to get as much as possible in-camera. The island of Ahch-To was the only location we really inherited from The Force Awakens, so we did go back to Skellig Michael [off the coast of Ireland] for a few days. There were so many production challenges with that location which we ended up solving by doing a build back at Pinewood and doing some location building along the coast of Ireland for the bulk of the scenes set [on Ahch-To].

The mineral planet Crait was another interesting challenge. We weren't sure what we were going to do for it. Rian wanted a white environment, and the question really was whether it should be a snowy environment, which would have hewn perhaps a little too closely to Hoth from The Empire Strikes Back [AC June ’80]. I was pushing the idea of a dry lake-bed kind of look, and then we discovered the largest salt flat in the world at Salar de Uyuni in Bolivia. We did a build on the back lot at Pinewood, and at the very end of the show some of the crew went down to Bolivia to shoot plates.

But the biggest challenge for me conceptually was Canto Bight, the casino planet. We really looked around for an urban environment that had an otherworldly feel. We ultimately chose Dubrovnik, Croatia, as we felt we could enhance and manipulate it with our own architectural elements to feel like the Star Wars galaxy. It also had this reflective quality on the streets and walls — an incredibly polished stone that felt slick and rich, like a jewel.

How do you go about designing practical lighting that harmonizes with what Steve Yedlin is trying to accomplish with the cinematography?

Heinrichs: Much of the lighting inside the ships was off-camera and ambient, but Steve wanted as much as possible for the illumination to read from within the set. There are no standard fixtures per se in the Star Wars world, so we had to come to grips with a very graphic depiction of light sources that ultimately become iconic imagery. For instance, there are these flat photon panels that have been graphically designed with these pill shapes dating back to A New Hope [AC July ’77]. Within that language, we came up with our own solutions for how those elements interacted with the new sets and complemented the architecture.

This is where the digital workflow of the art department really came in handy. Each set had a digital model that Steve and [gaffer] Dave Smith could study and fine tune as to how the lighting would either be a significant object in the composition or just be illuminating the scene. They were incredibly collaborative about all those conversations and very graceful in promoting what they needed without dictating to the art department exactly what they wanted.

Tell us about the use of the color red in the film.

Heinrichs: The way I perceived red entering the conversation was originally from Rian. He wanted it to be a significant part of the Crait battlefield scene. It was a combination of some of the tropes from The Force Awakens and some of the earlier Star Wars films. Red is used very sparingly in the original trilogy, but it usually has a very specific application — such as the Emperor’s guards in Return of the Jedi [AC June ’83]. We tried to do the same thing here without giving it any significance other than its intent within the scene.

This red was an intense, saturated and very specific part of the spectrum that Steve and Rian were after. So we were coming up with solutions that would work on the set as well as be something that the visual-effects could adapt to. It has a ceremonial aspect to it, which you see in Snoke's throne room — and a much more visceral and violent effect on the Crait battlefield. Star Wars is like a Western, with the black hats and the white hats; introducing red is another way of adding interest and a little bit of visual complexity while also keeping things simple.

What’s your dialogue like with ILM in terms of whether a set should be a full build or should incorporate digital extensions?

Heinrichs: That discussion stems from [George] Lucas trying to get as much as possible in-camera, and from what makes sense to build versus using either extensions or pure visual effects. We pretty much avoided any absolutely pure greenscreen stages; there was always something to ground the action and the characters in the foreground, because Rian wanted a truth and context for what was happening in front of the camera.

There was an interesting video I saw of [ILM chief creative officer] John Knoll talking about set extensions and how there's a sweet spot in mixing them with builds. The people at ILM are craftspeople and always want to refer back to the reality of light on real objects that the audience is going to respond to. That said, when it's a spaceship, unless there is a person in the foreground, that’s all pretty much a pure CG environment. As soon as you start to involve the actors, you really do want them interacting with cockpits at the very least. Some spaceships — like Kylo's TIE silencer, and the X-wings and A-wings — are small enough for us to build and use practically within a set. You then get the benefit of the light coming from Steve's amazing lighting [domes around the cockpits], and all of the interaction that happens spontaneously.

Then you get into the conversation of other environments and how you extend them. We tried to be as generous as practicality allowed us to be, and we ended up with 126 sets on 14 stages at Pinewood. There's just a quality to real, built sets that creates a sense in the audience of ‘being there,’ and a presence that is incredibly difficult to achieve purely with visual effects. That's not to knock down anything that visual effects does — and my experience with [visual-effects supervisor] Ben Morris and ILM was they really do appreciate the opportunity to have a seamless blend with the physical builds.

One other thing that helps us out is having a person from postproduction working within our art department as an embedded visual-effects art director. We had the incredibly talented Kevin Jenkins with us, who continued to work into postproduction.

All of the decision-making sensibility from the brain trust of Rian, Steve, Ben and myself came through pretty intact. I defy anyone to be able to really tell where the physical sets end and the digital sets begin.

How do you approach designing new vehicles that need to feel like they belong within the Star Wars universe?

Heinrichs: When I started working on The Last Jedi a few years ago, I visited the archives up at Skywalker Ranch to really get my head around what [designers] Ralph McQuarrie, Joe Johnston, John Mollo and a lot of the other amazing artists were working on. They've got drawers and drawers full of the original drawings, many of which I’m sure were just sketched out quickly and then cast aside. One of the great pleasures of working on this film was being able to go through all of that. It does take root when you study it.

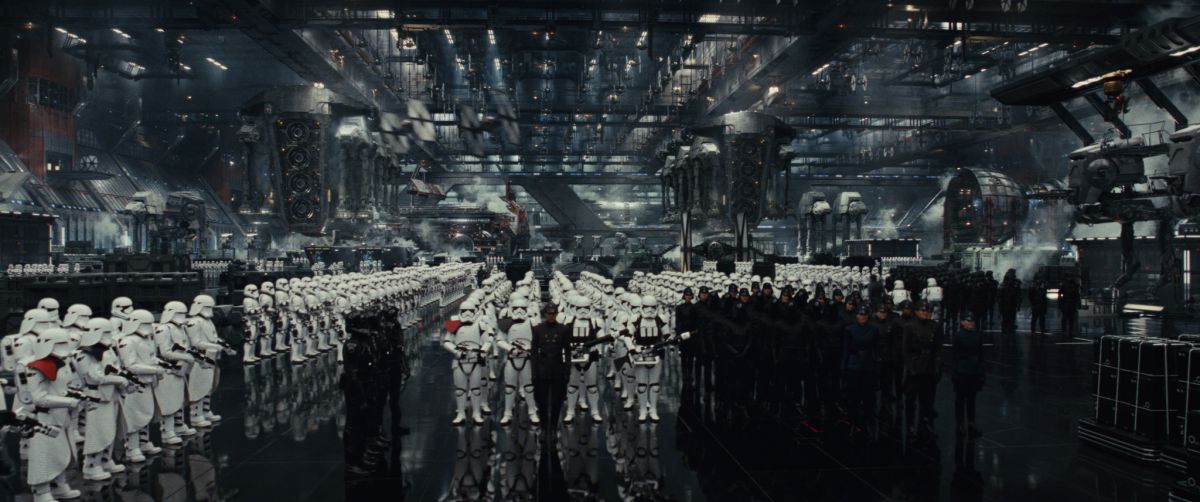

I've actually worked with Joe Johnston on a couple of films [The Wolfman, AC Feb, ’10; Captain America: The First Avenger, AC Aug. ’11], so I feel like I know his sensibility. You also get inoculated with the Star Wars approach to technology, going back to Lucas not wanting to call too much attention to specific things but rather to think in terms of overall ‘shape language.’ As a result, the Resistance/Rebellion is kind of more curvilinear and softer, which gives you more of a sense of the complexity of humanity. Meanwhile, the First Order/Empire is much more dangerous and dagger-like with a monolithic, fascistic simplicity.

Those aesthetic sensibilities go across all of the films and stamp the Star Wars look and feel onto them. As you drill into each element, you learn more. For instance they'd never actually made a full size A-wing before, but we built a couple of them to put into a scene. When you build something full-size, you continue to create within the scope of the original design and come up with new graphic solutions for the colors, for the markings, for all the different lines. It was glorious to be able to flesh out something like that.

What I loved about the original films was the spaceships had an expressive quality. Designing new ships was an incredible challenge, to make sure they still fit into the world that people are used to. I think we were successful. For instance, Rian wanted the Resistance bombers to feel partly like B-52s, but even more strongly he had this metaphorical image of this big herd of cows. They’re not the most agile or aggressive ships, but more these lumbering objects filled with dangerous explosives. We had to wrap our heads around that metaphor and then figure out how we were going to present it with all the elements Rian had in mind. The final version ended up being an incredibly beautiful and simple solution.

For the First Order, the Star Destroyers are part of the legacy you've got to maintain. At the same time, we wanted to enhance, develop, and push them forward, both in terms of scale and deployment. Rian came up with this concept of a ‘fuel tank destroyer’ and a ‘mega destroyer.’ Each needed its own look and feel while still being part of the original canon of Star Wars’ bad-guy hardware.

How did you design the ski speeders that the Resistance forces use on Crait?

Heinrichs: There was a history that Rian was layering on, and that had a lot to do with the way things ended up looking and feeling. We were going for something very utilitarian for the environment, which could relate specifically to the history of the mining aspect of this planet that was then co-opted by the rebellion in years past. The speeder is a vehicle that doesn't quite fly; it more glides and ‘hydrofoils’ along the surface of the planet, and feels kind of old. At the same time it also feels real because it’s adapted to the conditions of the environment it operates within. On top of that, we layered the aspect that they've been repurposed as attack vehicles.

It’s once again trying to figure out what the history is and how the nature of the planet dictates the intrinsic qualities of the vehicle itself. We did a lot of different ideas, like versions that more skated on the surface, but Rian really wanted something that hydrofoils, with a connection to the ground, just kind of plowing along. As a result, you get this great rooster tail of red that gets kicked up from the surface, which resonates a little bit with the attacking X-wings from The Force Awakens. It's a combination of us thinking about what makes sense for this environment and what also makes sense within the larger Star Wars [context] — how we can give it some continuity to the other films, and how we can make it true to what it needs to be for this particular environment.

The Imperial AT-AT walkers in The Empire Strikes Back moved liked elephants. In The Last Jedi, we see their technological descendants, the First Order’s AT-M6 walkers, which are more reminiscent of gorillas.

Heinrichs: One of the things that we respond to from The Empire Strikes Back is the walkers’ animal-like quality. Animals move around and operate based on all of their own physical characteristics and weight proportions. The way they look and move says a lot about what they do and what they are.

These new walkers are bigger, with an aggressive, simian-like attitude and motion, which actually allows them to better withstand the shock of firing at their enemy. The updated attributes have a very practical purpose to them, so that it doesn’t feel like an alternate look just for its own sake. Certainly there is that gorilla-like aspect, which is a concept I believe that Kevin Jenkins came up with originally. We were looking at a lot of different ideas on how to show variety but also have it make sense within the world. The ‘gorilla walker,’ as we were calling it at the time, was one of the ideas that we played with, and then it just started to feel right.

Did the original vision you had in mind for the movie evolve as the project came together, or do you feel you realized what you had in mind in your earliest discussions with Johnson?

Heinrichs: Everything I've seen so far is just like seeing Rian's initial pitch come to life. It's pretty remarkable to me because so many things can happen along the course of making a film. In my experience, good developments can happen — but in some cases the practicalities of making a film can tend to alter and somewhat degrade the original concepts. None of that seems to be happening in what I've seen from The Last Jedi. It looks like the original idea, and it looks like it was just done in absolutely the best way possible.