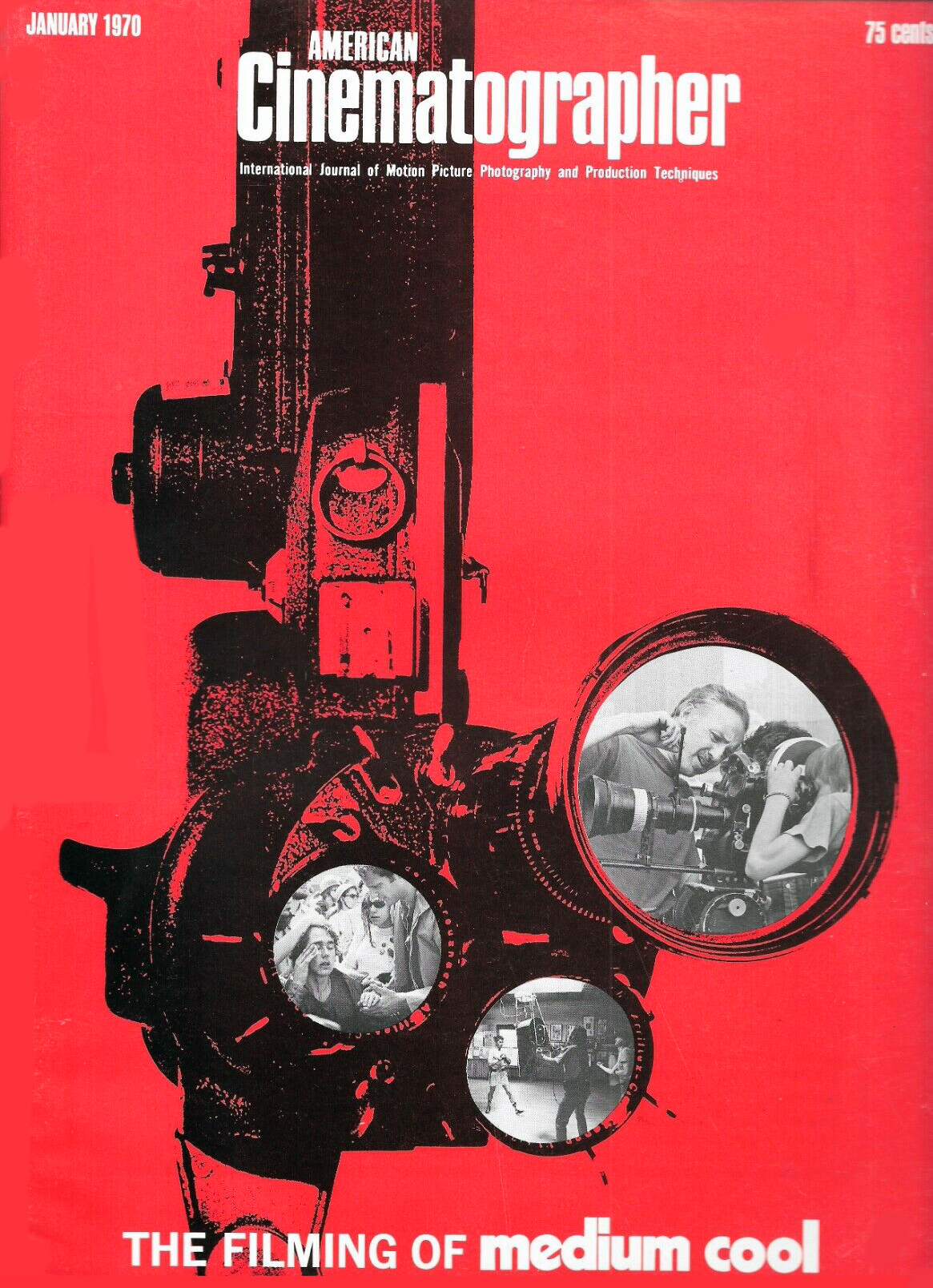

The Filming of Medium Cool

How Academy Award-winning cinematographer Haskell Wexler, ASC scripted, co-produced, directed, and photographed a cinema classic.

There have assuredly been men of multiple talents at work in the motion picture industry before (such names as Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, and Noel Coward come most readily to mind), but as far as I know Haskell Wexler, ASC, is the first to write, co-produce, direct and photograph a full-scale dramatic feature for major release. This work which bears his exclusive imprimatur is, of course. Paramount’s Medium Cool, a thought provoking, controversial, expertly made film quite unlike any other to grace the American screen.

“There is much to be gained by filming in and among people who feel things strongly. If your film can reflect areas of life where people feel passion, then it will have genuine drama.”

— Haskell Wexler, ASC

Wexler is much too sincere and down-to-earth an artist to banter about such currently overworked (and often misused) terms as “cinema verite” and “auteur theory” — yet his maiden effort in “complete filmmaking” is an almost classic example of both. The extraordinary verite derives from the skill with which the writer-director-cameraman has mixed reality with precisely controlled drama to arrive at a filmic truth that is more “real” in its effect upon the audience than, let us say, an actual newsreel of the events depicted. The auteur designation means, simply, that most of the major creative (and executive) functions of getting the story onto film were the work of a single, central, artistic mind — implying, also, total responsibility for the result, positive or negative.

What’s It All About?

The background and major locale of Medium Cool is Chicago in the summer of 1968, when the eyes of the world were focused on an unforgettable segment of American history: the Democratic National Convention.

Wexler was determined to capture the true spirit, essence and (as it turned out) upheaval of the event — and to this end, his extensive background as a documentary filmmaker served him in good stead. Not one studio scene was used for the entire film, and the characters responded with an authenticity that could never have been achieved on sound stages. Similarly, every line of dialogue was recorded on the spot — nor was any dubbing or looping of the soundtrack done later.

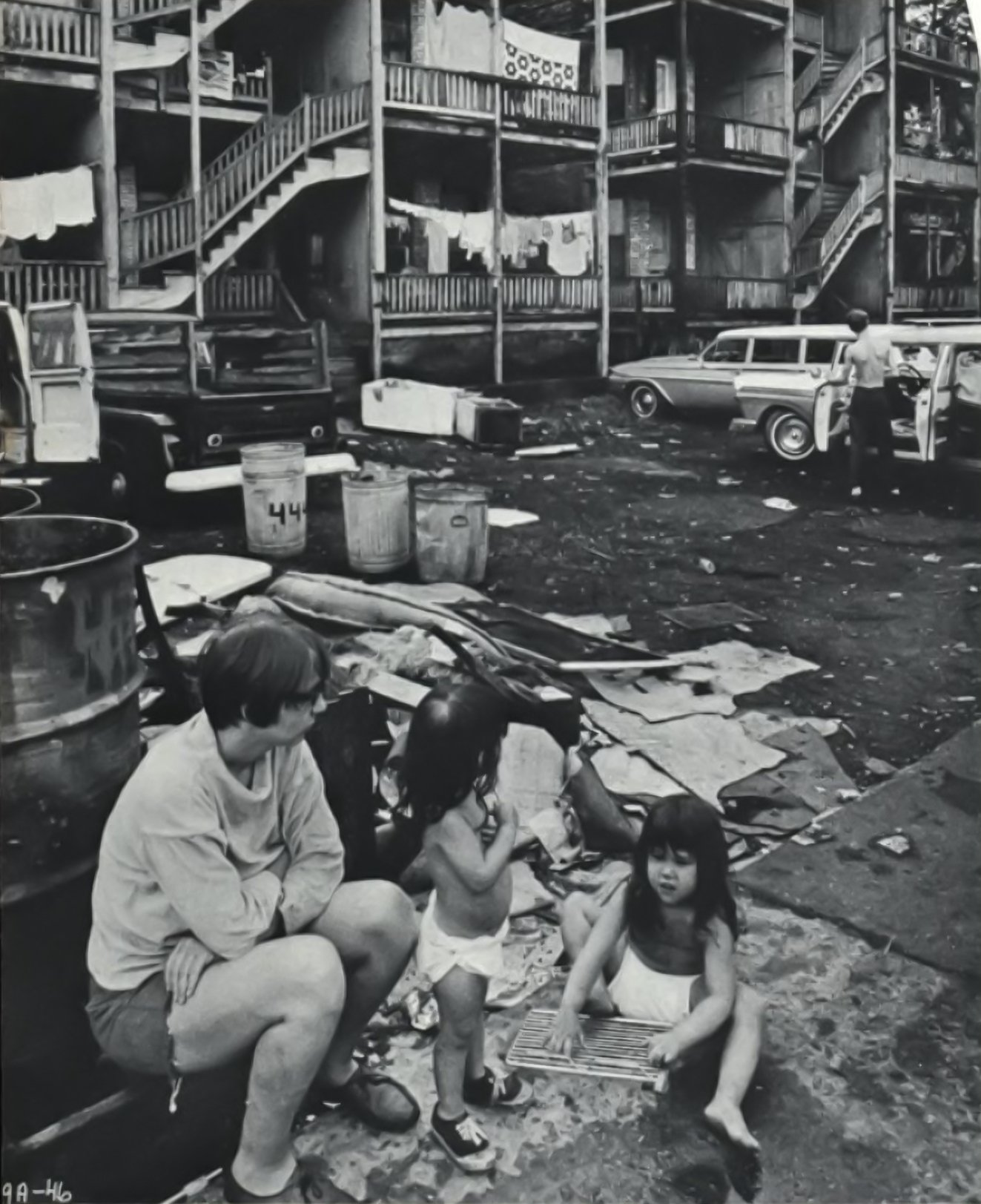

The scope of this unusual film encompasses more than the events at the International Amphitheater and the demonstrations in Grant Park. Much of it occurs in the Appalachian Ghetto of Chicago’s upper north side, where mountain people from Tennessee, Kentucky and West Virginia have settled into a life of poverty. Wexler had filmed before in that picturesque part of America and the lives of these almost forgotten people made a strong impression on him. When he read the book Division Street, America, by fellow Chicagoan Studs Terkel, he was greatly moved by the plight of those in the Appalachian Ghetto and in 1967, he began to work on a screenplay about them.

After President Lyndon B. Johnson announced that he would not run again and Chicago was chosen by the Democratic Party as the site for its convention, it became obvious that drama, excitement and history were certain to surround the event. Wexler proceeded to develop a script wich would incorporate the proceedings, keeping it flexible enough to utilize whatever newsworthy events might occur.

From his own experience as a cameraman, Wexler had learned that it was possible to avoid becoming emotionally affected by day-to-day events, but he felt that the temper of America today called for more involvement than most people permit.

To express his ideas, he selected a television news cameraman as the protagonist in Medium Cool. The cameraman, at first callous to the human elements of his daily assignments, finds himself becoming a part of the events he is assigned to cover and learns to evaluate them emotionally.

“There is much to be gained by filming in and among people who feel things strongly,” says Wexler. “If your film can reflect areas of life where people feel passion, then it will have genuine drama. I sincerely hope we have accomplished this in Medium Cool.

Starting Things Off With A Bang

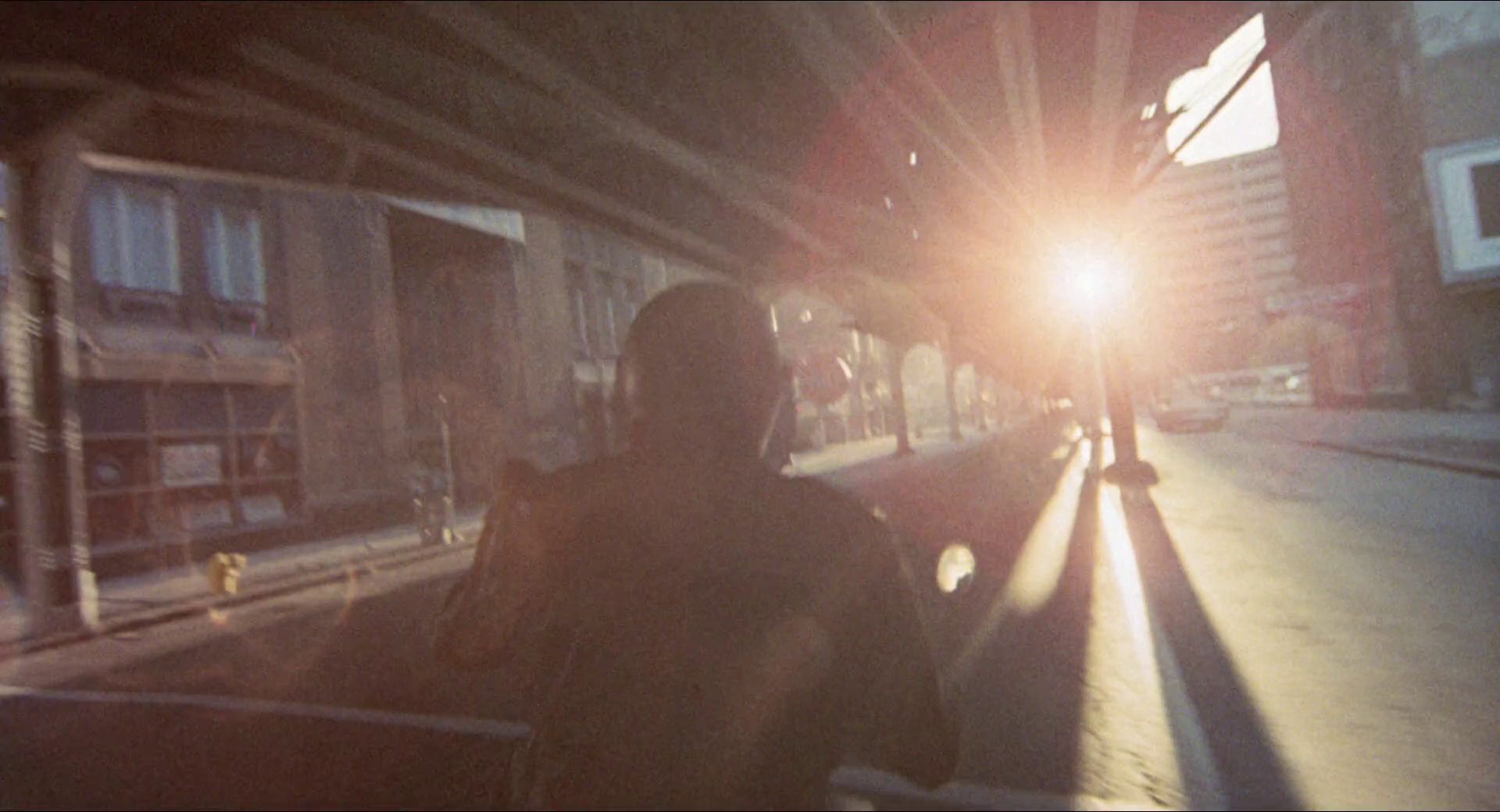

Medium Cool begins with a quietly jolting sequence before titles in which the TV news cameraman protagonist and his soundman coldly and methodically film a wreck on the freeway, then call for a lab messenger before (almost as an afterthought) summoning an ambulance to minister to the seriously injured woman driver of the car.

The messenger arrives on his motorcycle, takes the film can and rides off toward the heart of the city in a montage of magnificent images over which the titles are superimposed. In detailing how these stunning motorcycle scenes were photographed, Wexler explains: “I built a rig to fit onto the back of the camera operator who was riding a motorcycle behind the messenger. The camera was actually hand-held, but it sort of sat on his shoulder and rode with him. It was fitted with a 9.8mm extreme wide angle lens.”

At the end of this ride, the messenger draws up to the laboratory, gets off of his motorcycle and enters the building. The operator behind him kept his camera rolling as Wexler, who had been lying prone in the street to stay out of the shot, got up, took the still-running camera from the operator, panned the messenger around in front of his motorcycle and did a “walking dolly” with him down the street and into the lab.

It was one of those spectacular, tour de force of technique scenes and was faultlessly executed, but when viewed in the context of overall pace and continuity at that point, it simply ran too long. Wexler, torn between a cameraman’s pride and concern for the total effect, ultimately bowed to the latter and made a straight cut at the point where the messenger gets off his motorcycle.

“I would have loved to show off this scene because it was so hard to do, yet worked out so smoothly, but it just didn’t fit into the film, so we had to cut it,” he comments. “Cameramen always get excited about a challenging shot like this, but they find out that it doesn’t mean a damned thing to the people who go to the theater. This is something that is hard to realize, but we'd better realize it.”

An even more complex hand-held walking dolly shot was made inside the Appalachian ghetto apartment to cover the following continuous action: The woman enters her apartment at night and walks down the hall. She goes into her room, turns on the light and sits down on the bed. Then she gets her coat out of the closet, walks down the hall, looks into her boy’s room, turns on his light and sees that he is not there. She leaves his room, goes into the bathroom, turns off the water, walks through the living room and leaves through the kitchen door again.

All of this action was filmed in a single continuous shot, with Wexler smoothly propelling his hand-held camera to follow it. “But I also covered the same action in straight shots and cuts,” he points out, “just to protect myself in case the continuous shot didn’t work out or ran too long on the screen.”

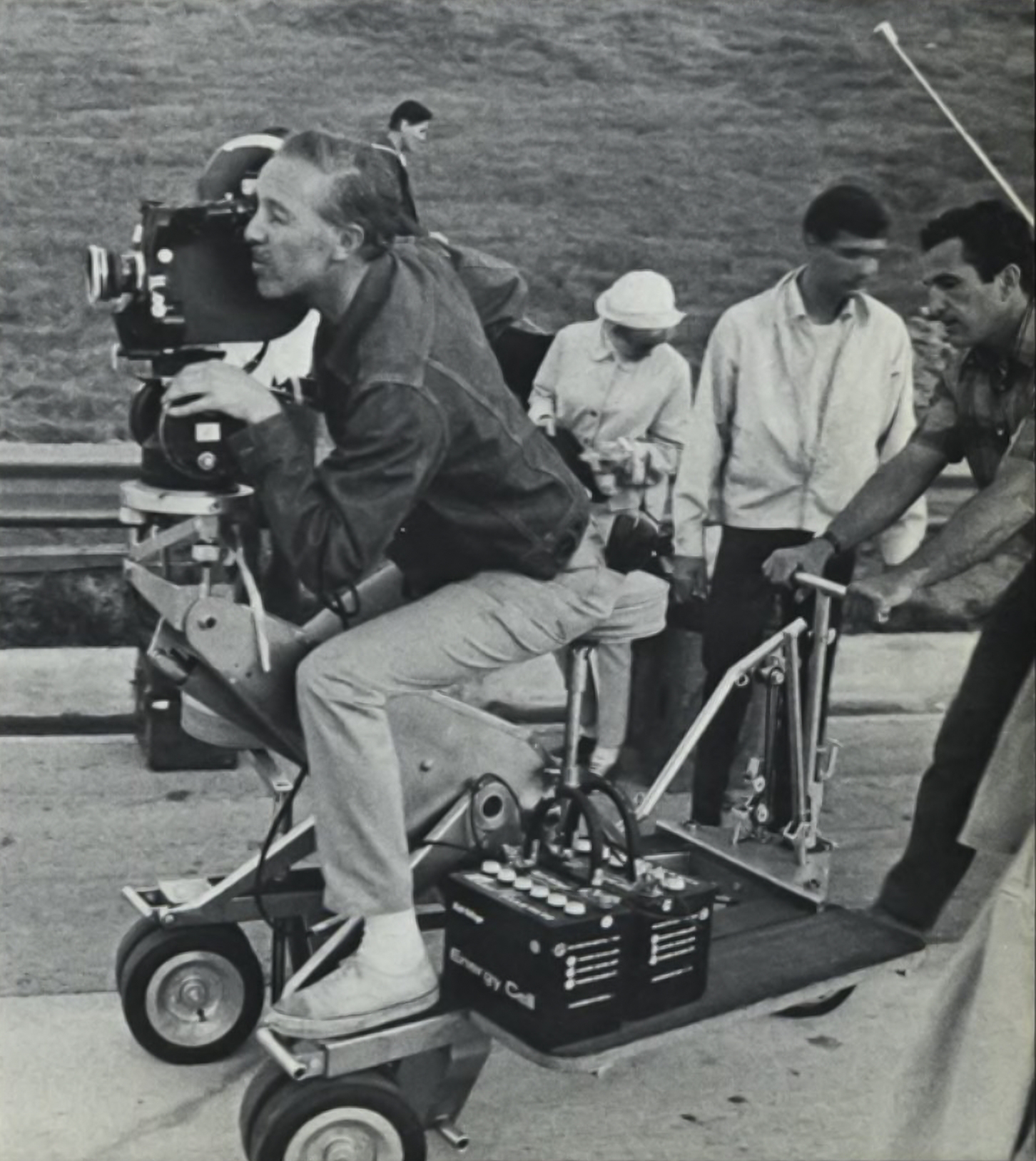

During the course of the filming, Wexler also used a number of very small pieces of equipment to move his camera fluidly in and out of some of the tight spots imposed by the actual location interiors. Particularly useful were the Fisher and Elemack Spyder dollies, plus his own wheelchair dolly which he originally designed for use in photographing Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (AC, Aug ’66).

Challenges and Triumphs of Lighting

Wexler’s approach to the immensely complicated task of lighting the many actual interior locations for Medium Cool was to try to get the result to look as realistic as possible. It is a tribute to his artistry that each scene looks as though it had been photographed solely by means of the illumination naturally available — which, of course, was not the case at all.

“Since I was directing the picture I didn’t want the cameraman to give me a hard time,” says Wexler, with tongue in cheek, “but since I was also the cameraman I decided to use the simplest lighting system I could think of, so that if I wanted to do a 360-degree pan around a room I wouldn’t have to re-light the set. For this reason, I used what was basically bounce light for photographing much of the picture — adding one or two hotter lights to snap things up a bit. However, with the exception of one sequence where 1,000-watt quartz lights were used, the lamps I employed were never larger than 750 watts.”

His reason for sticking with small lighting units, aside from their obvious compactness, was to keep the non-actors in the cast as unaware of the equipment as possible. “When you’re working with non-professionals you can’t spook them with the equipment — a lot of floor lamps, century stands and all that,” he explains. “It’s bad enough that you have a camera and a bunch of guys who are stretching tapes and blocking doors, so it’s best to keep the lighting equipment as unobtrusive as possible. You sometimes have to sacrifice a bit of photographic quality in this kind of compromise, but the performance is more important.”

To achieve the bounce light mentioned, Wexler used what he calls “space blankets” made of light-weight aluminized fabric. They are normally used as ground cloths under sleeping bags and such and are sold in sporting goods stores. The space blankets can be affixed to walls or ceilings by means of gaffer tape and the aluminized surface faithfully reflects the color temperature of the light directed toward it, including that of quartz lights and lamps fitted with dichroic filters for daylight balance.

“The space blankets solve a lot of location interior problems,” says Wexler. “For example, if you simply bounce light off of a bare ceiling there are a couple of things that could happen. For one thing, you’ll pick up whatever color the ceiling is. You may think it’s white, but it often isn’t. Secondly, you’re likely to ‘cook’ the ceiling and end up having to pay a re-paint bill. Besides being good reflectors, the space blankets insulate the paint from this heat.

“Speaking of faithful color temperature reflectance, I’ve found that when the white of soft-light reflectors becomes dirty or discolored the light will go warm. That’s why I often line soft-light units with aluminum foil.”

In photographing Medium Cool Wexler also used the unique aluminized umbrella reflectors which he more or less pioneered and which have since become fairly standard in still and motion picture work.

The Wonderful World of 5254

When Medium Cool was in the filming stage, Eastman’s 5254 color negative was just becoming available — but in sharply restricted quantities. Wexler tried desperately to get some of the fast new stock, but he was closely rationed.

“We were able to get enough 5254 to shoot some of the interior sequences,” he recalls, “and it was a very exciting experience, because after all the years of really lighting location interiors we found that if we simply put a brighter bulb in a practical lamp and got just the slightest amount of help from our movie lights, we would often get better lighting than if we’d spent five hours working at it.

"Of course, you still have to be able to recognize whether the natural lighting situation will be helpful to you or whether, in fact, you'll have to alter it. Natural lighting is like so-called natural acting. You still have to consider yourself an artist who manipulates nature to fulfill your dramatic needs.

Just because a room turns out to be lighted naturally in a certain way doesn’t mean that you have to accept it that way. If it doesn’t suit your purpose as a cinematographer — or as a director — you must change it, even though it happens to be natural the way it is.”

Neither booster lights nor reflectors were used to provide fill light for shooting exterior sequences of the film. This was partly because of the semi-documentary realism desired, and partly because much of the shooting was done on the fly under hazardous conditions and it would have been virtually impossible to place and maintain such equipment.

“Now, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t situations in other films shot under different conditions where such tools would help the picture to look better,” cautions Wexler, “but usually we had to make a compromise between calling attention to ourselves when working in the streets, or letting ‘nature take care of the shadows.’”

Speaking of Lenses

Wexler’s own Éclair 35mm cameras, used extensively in filming Medium Cool, have still camera lenses mounted on them. One is rigged for Nikon lenses, the other for Canon.

“These lenses are very fast, the longer focal-lengths included,” he explains. “They have extremely good resolution and the overall uniformity of quality is excellent, which includes color balance. They will focus as close or closer than the lenses ordinarily sold for motion picture work — and they are much less expensive. There is a wide range of these lenses available almost everywhere, and I think some cinematographers might do well to look into the possibility of using them for motion picture work.”

In the lens department, Wexler was able to get some “impossible” and very spectacular shots through the use of a 50mm f/.95 French instrumentation lens. This incredibly fast lens made possible the stunning night shots of downtown Chicago in which the girl of the story crosses a bridge and mounts a flight of steps next to the waterfront. Behind her, Chicago’s skyscrapers glow with tinted light, every detail sharp and clear.

Of this lens, Wexler says: “Using such a lens and forcing the 5254 one stop in development means that everything you can see with your naked eye you can photograph in color. The only problem is that, since it is a 50mm lens, you have very little depth of field when shooting wide open. However, if you mount it on a reflex camera and focus very carefully, keeping your main subject at relatively the same distance throughout the shot, you can get some very striking results.”

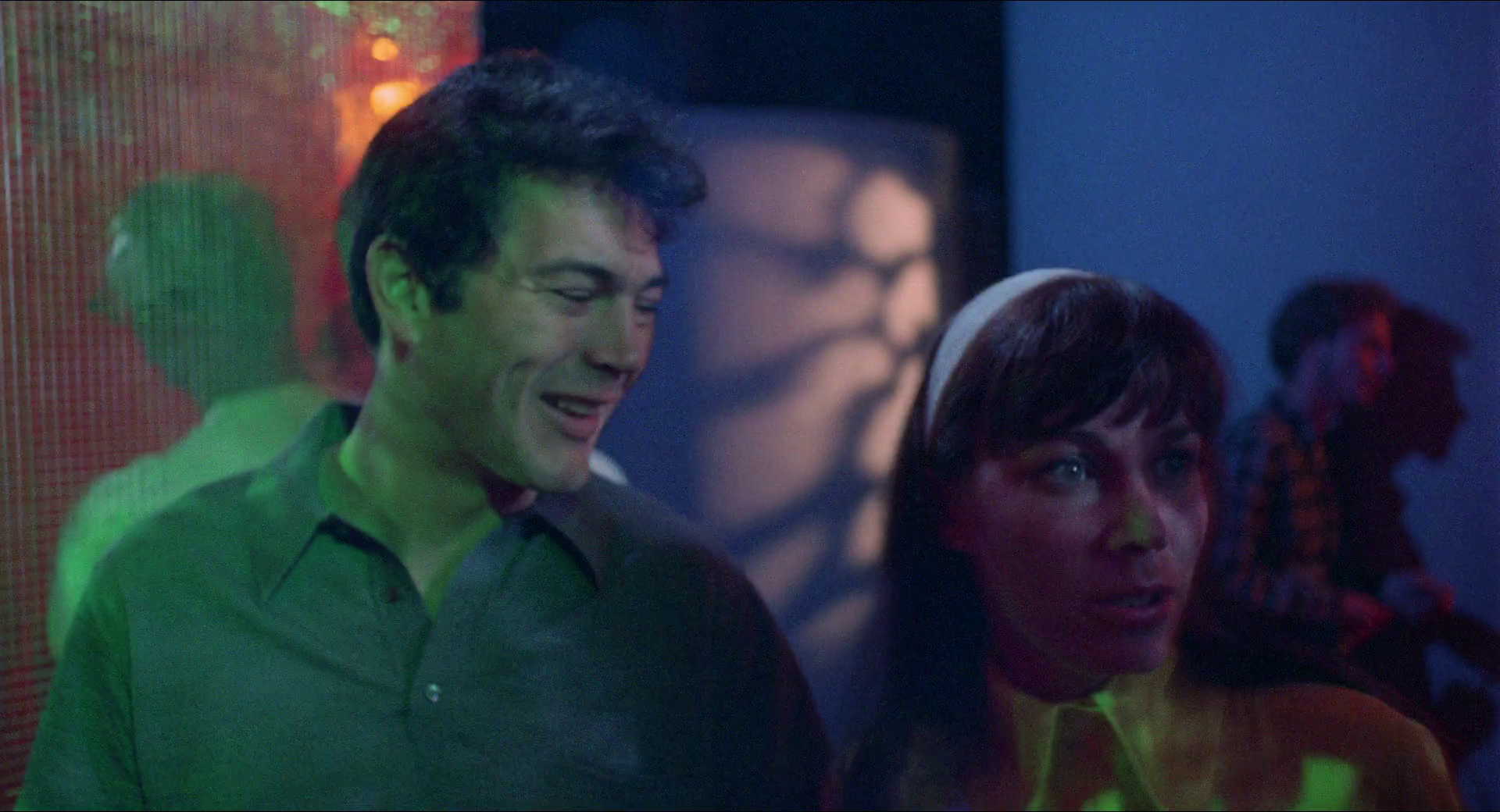

He did exactly that in a discotheque sequence where, in addition to the strobe flashes he was able to pick up clearly the subtle projections of the light show on the rear wall. The strobe effect was later intensified by the editor who cut a printing mask roll of alternating black and clear leader through which the sequence was printed. With the clear leader cut to coincide precisely with the frames where the strobe flashes occurred, the visual impact was greatly heightened.

In regard to forced development of the 5254 negative, Wexler agrees with most top professional cinematographers when he says: “We did a lot of experimenting in this area and found that it is possible to push it more than one stop, but when you do, there is some degradation. In general you should push it as little as possible — only as much as is necessary — but we found one stop to be very comfortable, with no problems at all.”

He is not of the school that feels that grain, per se adds to the aesthetics of the cinematic image, but he does say: “There are some times when grain can add to a film, but you have to consider all of the factors involved and ask yourself whether this corresponds to the overall effect which you want your film to have. If it does, and grain the size of golf balls will do it, then you’ve got it. But if a beautiful, unobtrusive image is what will do it, then that’s what you’ll have to get.”

16mm-to-35mm Blow-up

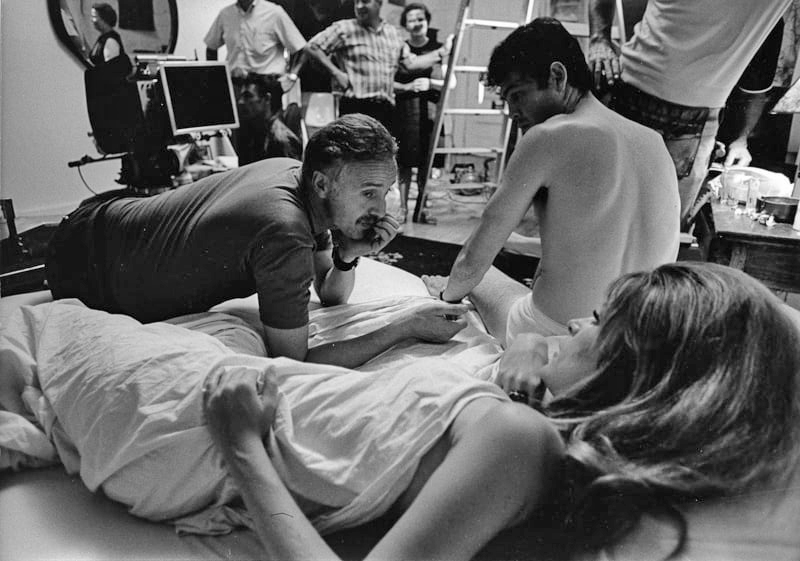

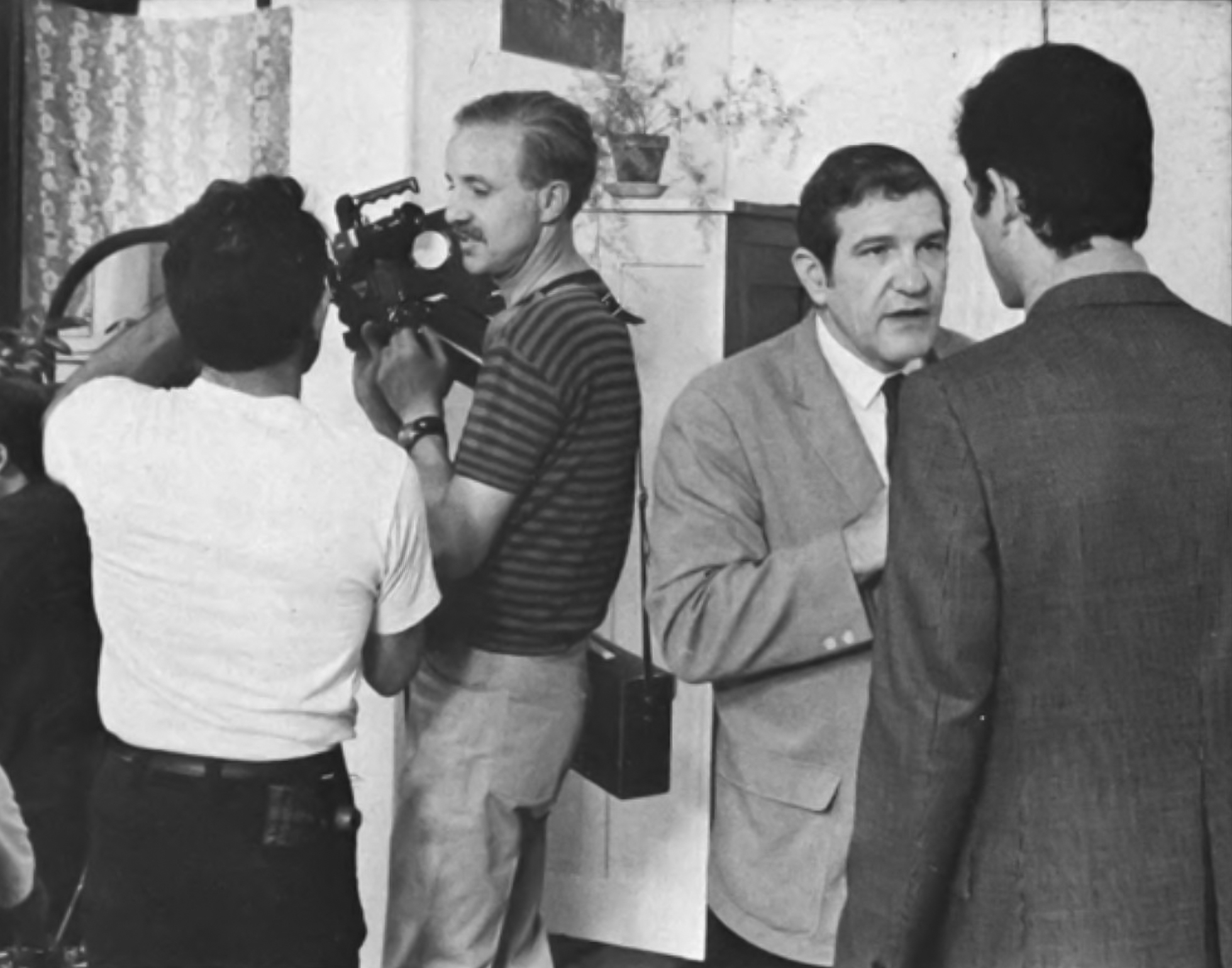

There is one sequence in Medium Cool (a party sequence near the beginning of the picture) which Wexler found necessary to shoot in 16mm and later blow up to 35mm. It is a party in which a group of newsreel cameramen and their companions discuss the peculiar dehumanization which can assail those whose jobs demand that they record daily the death, suffering, and violent aspects of a great city — actually the very crux of the picture’s theme.

In explaining his reasons for shooting this sequence in 16mm, Wexler explains: “The party was a real party. I invited most of my friends — newsreel guys, people in the TV media whom I have known over the years — and I told them that what we were going to do was talk about their job, what happens when they have to go out and cover violence in the streets and get right out into the problems of an urban center. Since these weren’t actors at all and since cameramen I have found are, as a group, more self-conscious than anybody else when they’re on the other side of the camera, I wanted them to be as relaxed as possible. So, rather than bring in a 35mm camera with a big blimp since this was to be a lip-sync sequence I decided to use the 16mm Éclair NPR. This made it possible for me to get a more easy, more honest response from them. I would have preferred to shoot it in 35mm, because it would have looked better, but the compromise was necessary.”

The enlargement to 35mm was made by Adrian Mosser at Cineservice of Hollywood, one of the industry’s acknowledged experts in the field, and it is so well done that no one but a top technician would be able to spot it as a blow-up.

Lighting of the party sequence presented some special problems, mainly because it was photographed in 16mm Ektachrome Commercial, which is considerably slower than the 35mm 5254 stock used in filming some of the other interior sequences.

It was here that Wexler used 1000-watt quartz lamps, and because he wanted to be free to pan in any direction, all of the lamps were mounted at the ceiling with some rigged for bounce light. A tungsten balance was used in order to have the advantage of the extra speed of the Ektachrome emulsion minus the daylight filter, but this meant putting 85 gelatins over the windows.

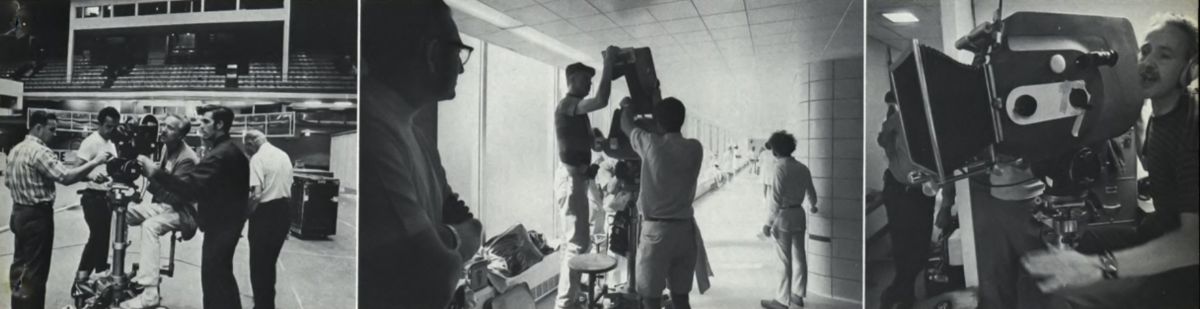

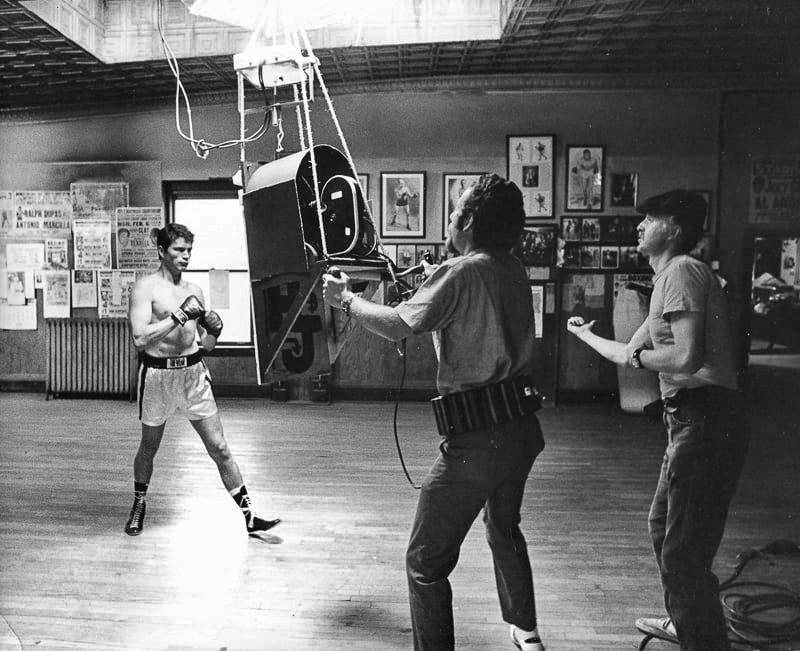

During the filming of Medium Cool, Wexler had the advantage of two innovative pieces of equipment, both designed by cameraman Carroll Ballard. One of these was a 1,000' coaxial magazine which snaps onto the 35mm Éclair, so that the camera can be handheld very easily. It fits flat to the shoulder just like the standard 400' magazine and should prove very advantageous in shooting such things as major sporting events in which it is necessary to shoot a great deal of footage and change magazines very rapidly so that a minimum of the action is lost. Ballard also designed and built lightweight magnesium blimps for the Éclair to accommodate 200', 400', and 1,000' magazines.

It is this strange-looking configuration that is seen at the end of the film when Wexler, having killed off the main characters of his story, turns his camera lens directly toward the audience.

Always the innovator, Wexler demonstrates Medium Cool that his virtuosity extends not only to imaginative uses of equipment, but also to the solving of the myriad problems that can arise when you elect to write, co-produce, direct, and photograph your own feature. Despite the fact that he accomplished this with great style and impact, he still maintains that the making of a motion picture is, ideally, a “team” effort.