Photographing Days of Heaven

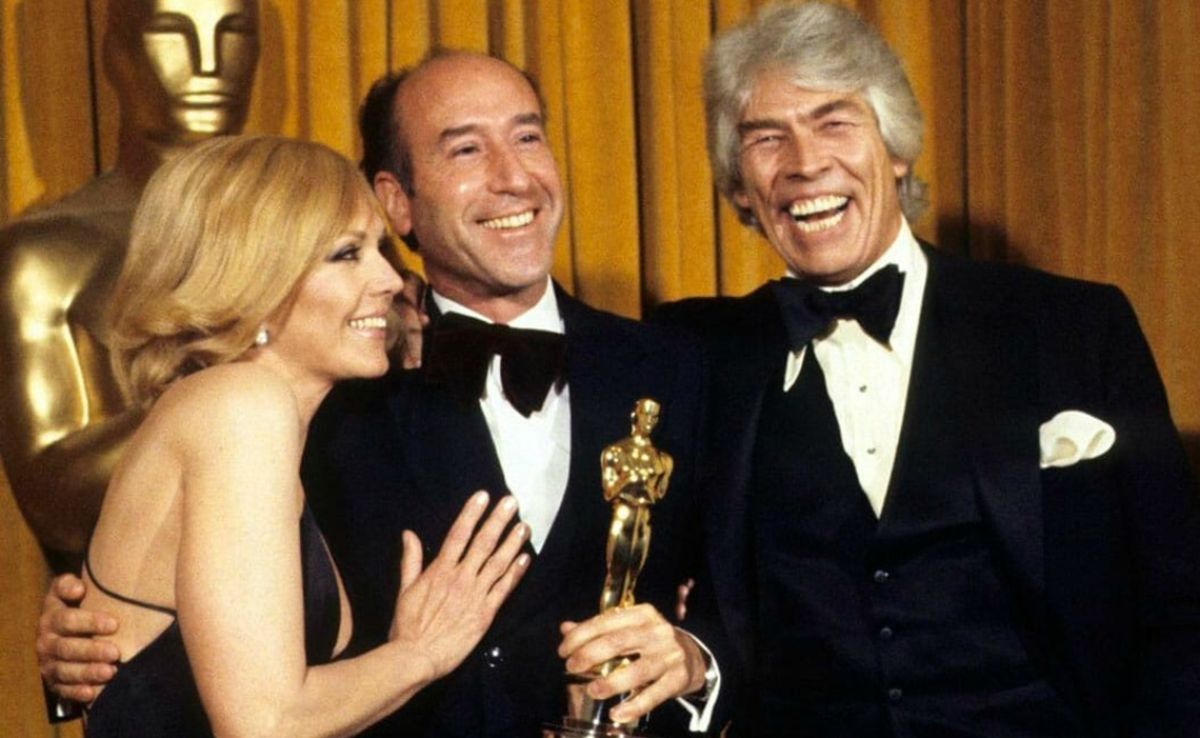

The winner of 1979’s Academy Award for “Best Achievement in Cinematography” discusses the techniques he employed that resulted in all those stunning images on the screen.

Translated by Hal Trusell

As a cameraman, I am drawn naturally to the works of visual directors. In particular, there are three American directors I consider masters of visual presentation: King Vidor, Josef Von Sternberg and John Ford. Their interest in set design, camera angles, composition and lighting combined to produce films of time-tested originality and expression.

These men were, above all, visual directors, and, in spite of their reputations for complex and detailed aesthetics, they maintained a simplicity of the essential in their lighting preferences.

In their films, the light is united to the mise-en-scene to the extent that it actually becomes a part of the mise-en-scene. Their total integration of light and visuals has always been a guide for me, and it was this artistic preference which drew me to Terrence Malick and his project Days of Heaven.

When producers Harold and Bert Schneider first contacted me regarding Days of Heaven, I asked to see Malick’s previous film, Badlands. On the basis of this screening, I immediately realized that Malick was a director with whom I could establish a unique and productive collaboration. Later, I learned that Terry greatly admired my work in L'Enfant Sauvage (The Wild Child), which, although black and white, was also a period movie with similarities to Days of Heaven. As a matter of fact, it was because of this film, directed by Francois Truffaut, that Malick asked me to photograph Days of Heaven.

In the filmmaking process, the communication between a director and a cameraman is often ambiguous and confused because the majority of directors don’t understand the technical details required in cinematography. With Terry, there was never any miscommunication. He always understood exactly my cinematographic preferences and explanations. And not only did he allow me to do what I had always wanted to do — which was to use less artificial light in a period movie than is conventionally used (many times I used none at all) — but he actually pushed me in that direction. Such creative support was personally exciting and directly enhanced the work I was doing.

Our creative work consisted basically in simplifying photography: cleansing it of the artificial glossy look of the films of the recent past. Our models were the films of the silent era, (Griffith, Chaplin, etc.), when cinematographers made unique and fundamental use of natural light.

Using natural light as often as possible meant using only natural window light for day interiors, like the great Dutch painter Johann Vermeer. For night interiors it meant using very little light, from a single justifiable source, such as a lantern, candle, or electric light bulb.

“For this particular project, I was influenced primarily by American painters such as Andrew Wyeth and Edward Hopper.”

In this sense, Days of Heaven is a homage to those creators of images in the years before sound whose works I admire for their raw quality and for their lack of artificial refinement and gloss.

Cinema — the visual presentation of film — became very sophisticated in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. As a filmgoer, I like the photography of these films, particularly the early sound pictures, but it is not the style I look for in my own work.

As in all my films, I was inspired by works of great painters. For this particular project, I was influenced primarily by American painters such as Andrew Wyeth and Edward Hopper.

Besides being a very educated and knowledgeable man of the arts, Terry Malick is also a collector of classic still photographs. His collection of turn-of-the-century reproduction books became a guide for designing clothes and sensing the mood of the people of the era.

Eventually, we felt these stills to be such an influence that they were the first images chosen for the audience to see during the title sequence, thereby setting the mood and sense of period for the picture.

With Bill Weber’s editing, these title images follow one another in a visual classic symphony, with andantes, maestossos, staccatos, tremolos, etc.

To develop a design and style for this particular film, my first consideration upon arriving on location in Canada was the character of the natural sunlight.

The light in France is very soft and subtle because of a mattress-like layer of clouds that covers the sky, making work in exteriors very easy, shots matching each other from any angle without modification.

In North America, however, the air seems more transparent and the light more harsh. When a person is backlit, his face appears to be in dark shadows to the eye of the film.

In filming day exteriors, the normal procedure is to use reflected or artificial light (such as an arc) to fill the shadowed areas and thereby reduce the photographic contrast.

In this film, however, Malick and I felt it would be better not to follow convention, to use no lights, and to expose instead more for the shadowed areas. The effect of this was that the sky would come out overexposed (“burned”), thereby losing its blue hue. This was an effect that pleased Terry.

Malick, like Truffaut, follows today’s tendency to eliminate color. The blue sky bothers them. They seem to feel that the blue sky gives the landscape a postcard quality, as though it was put there for vulgar tourist publicity.

“My work became ‘de-illuminating,’ that is, removing the false and conventional light.”

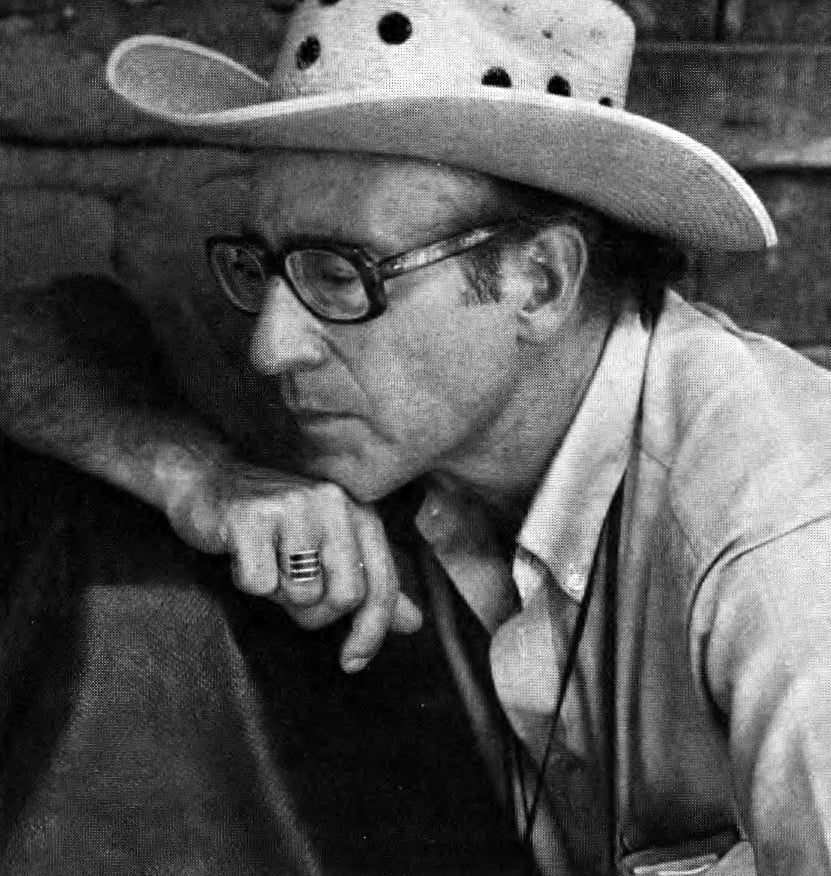

Néstor Almendros lived much of his youth

in Cuba and has, for several years, been a resident of Paris.

Straight exposure of shadow in backlit situations would have given us a “burned out” sky — white, colorless. Using arcs or reflectors would have made the scene flat, without dimension and not very visually interesting.

I decided to forego the use of any artificial or reflected light, and to split the difference between my reading for the sky and my reading for the shadow, resulting in faces being slightly underexposed, and the sky slightly overexposed, taking away thereby the intensity of blue, yet not letting it burn white.

Surprisingly for me, this creative decision became a primary point of dissension among the technicians.

The circumstances of a European cameraman working on a major studio film precluded me from being able to select the technicians who would work for me. Instead, the producers assigned the technicians to the production. With very few exceptions, the crew was made up of the typical Hollywood old guard.

They were accustomed to a very polished form of lighting and photography. For them, the faces should never be in shadow and the sky should always be blue. I found myself walking onto the set with the arcs in place and ready for each scene. My work became “de-illuminating,” that is, removing the false and conventional light.

I could see members of the crew were very unhappy with our creative approach to this film, and some began openly to comment that we did not know what we were doing, and that we were not “professional.” At this point, as a gesture of goodwill, we would do one take with the arcs, and another without. We then invited the dissenters to view the rushes to see and compare the results and offer their comments.

This creative conflict became more accentuated as filming progressed. I was fortunate that Malick not only sided with me, but was even MORE daring. In scenes where I initially felt it necessary to use a sheet of white Styrofoam to bounce a little sunlight into an actor’s face to slightly reduce the contrast, Malick would ask me to shoot without it.

“Some of the crew began to see what we were doing, and, little by little, joined our interpretation. Others never understood.”

Since we could see the rushes immediately and it was apparent the results were adding to the visual presentation of the story, we became more and more daring, using less and less artificial light, preferring the look of the raw, natural images. Some of the crew began to see what we were doing, and, little by little, joined our interpretation. Others never understood.

If on the one hand there were conflicts with some of the technicians, on the artistic level I had the good fortune of working with some of the very best collaborators I could have imagined. In each film, there is actually a very small group of people who are really responsible for “creating” the film. On Days of Heaven this group consisted of about six or seven individuals:

Production designer Jack Fisk, who designed and constructed the mansion and the shacks where the migrant workers lived.

Patricia Norris, costume designer, who created with great taste and extraordinary sensitivity the clothes of the period.

Jacob Brackman, an associate of Malick’s, who was in charge of second unit; and, of course, producers Harold and Bert Schneider.

“Throughout the production of Days of Heaven, Terry created an atmosphere and space for improvisation, enabling us to take advantage of each moment.”

Each day, this group would ride in a large van from the hotel to the wheat fields. The trip was an hour one way, and invariably we would talk about the film. In this way, this group would have an improvised special production meeting each morning. The effect of such a creative unity and focus in the actual production of a major film cannot be discounted.

Between the set decorator, props, and wardrobe, we selected combinations of colors that were muted because historically colors then were not as bright and aggressive as colors today.

Patricia Norris created old clothing and dresses that didn’t have that synthetic look or quality that is recognizable in the finely machined clothing of today.

The mansion was built solid in the middle of rolling wheat fields. It was a real house — both inside and outside — not just a facade, as is typically done for a film. Even the colors and selection of the wood were period, all dark and realistic.

“You cannot achieve good photography — photography with a particular style and grace — unless you work hand in hand with the set designer and the costume designer.”

Many people in the film business think the director of photography need only be concerned with the camera and related technology. I believe that the director of photography must also work closely with everyone involved in the visual presentation. The truth is, you cannot achieve good photography — photography with a particular style and grace — unless you work hand in hand with the set designer and the costume designer.

If poor taste is used in the selection of the items that will visually appear in the film, then no matter how striking the work of the cameraman, the strength of the visuals will always be diminished by the ugliness or inappropriateness of the items within the frame.

You cannot get beauty out of ugliness; unless you aim for the oxymoron of Andy Warhol, who found “ugly beauty.”

There were several camera operators for this film. Contrary to the films I do in Europe, (for union reasons) I was not allowed to operate a camera. Of course, I lined up the shots, and rehearsed their visual design with Terry (the movements of the camera and the actors inside the frame). Considering the situation, I was fortunate to have four camera operators of great skill and talent. From Hollywood, John Bailey; from Canada, Rod Parkhurst; Eric Van Haren Noman, the Panaglide specialist, and the second-unit camera operator, Paul Ryan.

To be fair, the praises given to my work should be distributed among these and other anonymous technicians, especially in the multi-camera scenes where one camera shot wide-angle, another detailed with a telephoto lens, and another was hand-held — all while the Panaglide slid through the flames and around and in between groups of people. And, finally, Haskell Wexler, ASC, who supervised the last three weeks when I had to leave due to a prior commitment. ALL this was unified by the immense talent of Terry; thanks to his technical knowledge and his infallible taste.

When I was initially contacted by producers Harold and Bert Schneider, I advised them of my commitment to Truffaut, which would begin just as Days of Heaven was scheduled to end.

Malick and the Schneiders accepted this condition with the hope that Truffaut’s film, The Man Who Loved Women would be delayed in pre-production. It wasn’t, and, to complicate matters, Canada experienced an Indian Summer and the snows we needed for the story were late in coming.

Once the situation became apparent and I knew I would not be able to finish the film, I thought of all the great directors of photography in America, searching for someone who would be appropriate to replace me. I thought of Haskell Wexler, a man whose work I greatly admire, and a man I also consider a friend. I asked him if he would complete the work I had begun, and again, fortunately for me and the project, he accepted.

He overlapped with me for one week, observing the style we were using, screening all our rushes, sensing what we were after.

In the end, I had shot for 53 days; Haskell shot another 19. I don’t believe anyone can tell the difference between what I shot and what he did.

He was directly responsible for the final scenes in the city, after the death of Richard Gere; for all the snow sequences; and for completing shots in other sequences where additional angles or coverage was necessary.

The continuity Haskell achieved is a remarkable achievement; an example of his immense talent for which I am forever thankful.

As often happens in films, a story with a particular setting may actually be filmed in a totally different locale that has the appearance of the real setting. Such was the case with Days of Heaven.

Set in the Texas Panhandle in 1916, the film was made in Canada, in a region of southern Alberta. And, as so often happens in filmmaking, the elements of the location directly enhanced the design of the film.

The locale chosen was a vast virgin landscape owned and farmed by the Hitterites, a religious sect who emigrated many years ago from religious intolerance in Europe. Like the Mennonites and Amish in America, these people live in another era.

They communally own and work the great stretches of land, growing a wheat that is longer than the kind grown by modern farming today.

They make all their material possessions, including their austere furniture. They have no radio or television, eat homegrown natural foods, and even their faces look different from ours (some appear in the film). In the one-hour drive from our hotel we would pass from the 20th to the 19th century.

There is no doubt that the atmosphere of this land added authenticity to the images in our movie.

In addition, rising out of and rolling across this extraordinary landscape were red-wine-colored silos and antique, steam-driven tractors and combines loaned to us from nearby private collections.

Days of Heaven was my first opportunity to use a camera which was the rage in America but hadn’t yet arrived in Europe: the Panaflex.

It is a very light, self-blimped, late American answer (but I believe superior) to similar European cameras.

Today’s evolution is toward the miniaturization of equipment that will afford more freedom of movement during shooting. To this end, the Panaflex was developed, with such versatility that now we have a studio camera with the flexibility and configuration of a documentary or newsreel camera. During our production, its only drawback was a dim viewfinder, something that has since been corrected with great ingenuity.

It is a highly sophisticated camera, and adding the ultra-speed lenses, filming that was once impossible is now available to us all. Days of Heaven could not have been made without this camera and those lenses.

Over the years, I have noticed a certain inertia among Hollywood technicians. Since they were the first in everything, it takes them time to catch up to date or to accept the need for modification or new design.

After World War II, Europe was at the forefront of new equipment development. Light cameras were among the first items developed, allowing the filmmakers to be freed of the confines of only studio sets. As a further development, these cameras were made as reflex cameras, something that did not happen in America until much later.

Another example of this inertia is the use and development of the dolly. I prefer simple movements — and I find handiest for this the Italian Elemack, which is very versatile and light. On Days of Heaven, the crew was determined to use a conventional studio dolly with hydraulic riser — a piece of machinery so heavy it takes six men to lift it, and its size precludes it from fitting where you need it. Obviously not a flexible unit for filmmaking.

I suppose there is an American weakness (or perhaps human weakness) which prompts men to resist simplification.

Typical of this resistance is the continued use of the gear head. Today there are gyroscopic and hydraulic fluid heads which move the camera as smoothly and directly as the old-fashioned gear heads, or even better. (Sachler and Ronford are two perfect examples.) It does not require a great deal of experience to use them — a person with a good sense of rhythm can make a perfect panoramic sweep and accompany characters in their movements without losing the composition.

With a camera on a simple head with a handle, the man and mechanical elements become one, and the movement becomes almost human. The mechanical perfection of the gear head cannot compare with the almost human sense of a handmade panoramic.

If Americans resist on the one hand, on the other hand there is no doubt that when they put their mind to something, they are the greatest technicians and innovators in the world. And doubly praiseworthy is that whenever they seriously attack a technological problem, they offer the results freely to any nation.

On Days of Heaven, we were fortunate to have a perfect example of this ingenuity: the Panaglide System. This is Panavision’s version of the Steadicam System, with several advantages.

In the beginning, Terry was very enthusiastic and wanted to do practically the whole movie with Panaglide. Very soon, however, we realized it was a useful gadget, virtually indispensable on occasions, but not universal.

Like the first filmmakers, who used the zoom lens and were so enthusiastic over their new toy that they made audiences seasick, we too paid to be freshmen.

Because we had the freedom to move in all directions, the thing became a merry-go-round. The whole crew sound, script, director, and myself — had to run behind the operator on every take so we would not be in frame.

The dailies were incredible — brilliant; but there was an impression of tour de force, of great effort. The camera became a protagonist, a living actor; and it was an intruder. We discovered that very often, nothing is worth more than a steady shot on a tripod or a very smooth, invisible classic dolly move.

Nevertheless, the main sequences and shots in Days of Heaven could not have been done without a Panaglide. It is these scenes that the audience and the critics continually talk about.

For instance, there is a scene in the river where Richard Gere convinces Brooke Adams to accept the marriage proposition of Sam Shepard. This scene required movement, yet it would have been impossible to put track under the water for a dolly. Further, the actors improvised in the water, wading around knee deep, moving wherever they wanted without blocking, and the camera never lost them. Only the Panaglide made that shot possible.

Similarly, in the fire sequences, the camera could penetrate the flames and move around in a brilliant vertical movement that visually heightened the drama of the moment.

Juxtaposed with these brilliant takes were editing problems. The novel improvisations of the actors and the camera prevented several cuts without continuity problems.

Also, it was quite difficult to shorten a sequence, and for this reason one of the most perfect scenes had to be eliminated in the final cut. The operator was standing on the crane arm, even with the balcony on the third floor of the mansion. Linda Mantz walked into the house from the terrace, through the bedroom, and down the stairs. The crane boomed down at the same time, following her, and we could see her intermittently through the windows. When she reached the ground floor, the operator stepped off the crane, and moved step-for-step with Linda, following her into the kitchen, where she encountered Richard Gere, and they exchanged dialogue (in sync sound).

The first part of the shot, the crane following her down the facade of a building, and describing along its way several actions as seen through the windows is nothing new. King Vidor did it in Street Scene; Max Ophuls in Madame De. On the other hand, what follows — the camera actually entering the building, is very, very new.

The French invention, the Louma, could penetrate into the building at the end of Madame Rosa, but only in one room because it cannot twist; it cannot bend and follow a character into another room. But with the Panaglide, you get the true impression of three-dimension and the real geography of the set is described perfectly.

For all its magnificent possibilities, however, the Panaglide has one very serious drawback. The weight of the system is considerable and the operator has to be an Olympic athlete. If the system becomes standard equipment in the state it is in now, we will have to create a whole new generation of cameramen athletes, and the problem will be to find athletes who are also artists.

All three operators and myself tried to operate the apparatus, and we all gave up, breathless. Undoubtedly that is why Bob Gottshalk at Panavision sent a special operator with the camera; a very well-trained athlete, Eric Van Haren Noman who did his push-ups all day long, and who is also a great artist.

From the very start of filming, I consistently pushed the night scenes. A few years ago when 5247 was first released, the results of forcing the film were not very good, but when we began Days of Heaven, the response of the new stock had come to perfection, and our tests at Alfa-Cine Laboratory in Vancouver were more than satisfactory.

Our night scenes were overdeveloped one stop, to ASA 200, and in extreme cases, two stops, to ASA 400. Astonishingly, the grain was not noticeable, even with the 70mm blow-up.

These ASA ratings, combined with the new ultra-speed lenses, enabled me to shoot at lower light levels than I had ever done before. For example, the speed of the 55mm lens is T/1.1, and you can literally shoot with the light of a match or a flashlight. Very often we would shoot at T/1.1, pushing one-stop, without the 85 filter, using the last glow of the day.

Even though I was sure of the exposure, I was concerned about the focus, since the depth of field was at an absolute minimum, and my concern doubled when we began to consider blowing the release prints to 70mm.

Again I was fortunate to have a second assistant who was an artist. Michael Gershman was responsible for the focus, and he knew he was gambling with his job. Difficult as his task was, he proved himself to be a perfectionist, and he rehearsed and rehearsed until he was sure of his gauge. Whereas some became impatient with him, I can never thank him enough for his dedication. I was using no diffusion and I wanted a very crisp, clear image. The sharp images in the film are directly attributable to his professionalism.

Professional cinema does not risk underexposure and focus very often, but Malick wanted the film to have a certain style, which carried with it those risks. To achieve this style, he allowed me to go very far — as far as I wanted.

The night exteriors in 1917 would have been illuminated by bonfire or lantern. In our bonfire sequences, to give the impression of reality, our challenge was to light the scene as though the light came only from the flames.

Westerns are famous for these scenes, when the characters are sitting around the campfire. Usually electric lights are hidden behind the firewood to increase the natural light given by the flames. I always thought these scenes looked very fake.

Even in a marvelous movie, like Dersu Uzala, they have a photographically ridiculous scene near the fire. Not only is there too much light, even overpowering the flames, it is white, conflicting with the color temperature of the fire and ruining the atmosphere.

Another often-used technique is to shake things in front of the lights to give the impression of flickering flames across a person’s face.

All these methods were always unsatisfactory to me, so I was looking for a technique to use real fire to light the actors. As with all discoveries, the solution that presented itself was a fortuitous coincidence.

When we prepared for the bonfire sequences when the workers celebrated the end of the harvest, I saw the special effect of controlled fire was made by regulating the flow of natural gas through a pipe or tube with several openings. It was from these openings the flames would generate, regulated by the valve on the propane bottle. With this valve the height (and therefore illumination) of the flames was controlled.

We held one of these pipes next to the camera and created the only supplemental illumination in the bonfire sequences. We lit fire with fire — with its own color, its own movement. My exposure was between T/1.4 and T/2, pushing the film one stop, to ASA 200. I think that not only did we capture authenticity, but also beauty.

Similarly, the huge vistas of the burning wheat fields were shot with practically no artificial enhancement. For if you illuminate fire artificially, you diminish the power of its visual effect.

In super-productions with huge fire scenes, a mistake often made is overlighting, and thereby spoiling the effect. Principally I think this is done because the director of photography feels almost obliged to justify his salary and his presence by using all his electrical paraphernalia that supposedly impresses everyone.

Our large fire sequences of burning wheat fields took two weeks of night work. Each night we would burn a new field. The excitement and drama on the screen was nearly outweighed by the tension of the actual situation.

Though all precautions were taken, the fires were difficult to control and once we found ourselves surrounded by flames, the air asphyxiating. The entire crew, grips, wranglers, and transportation acted very quickly and loaded everyone and the equipment into trucks and drove through the flames to open ground.

It was a moment of fate that could have turned either way, but this was a blessed movie, protected by the gods.

Like the fire scenes, the night lantern scenes needed to appear as though the light actually came from the lanterns, rather than using the lanterns merely as props as is traditionally done in films.

To create the effect of such realism the lanterns were electrified, the wires running up the actors’ wrists to a belt battery they wore under their clothes. For color, the lantern crystals were painted a deep orange. For these scenes I usually used a very soft frontal fill colored with a doubled 85 orange gel. This supplementary light was only to add a little exposure and color to the shadow areas.

Days of Heaven was the first time I used a new method for photographing back- and front-lit actors whose shots would be intercut as cross-cuts.

When shooting exteriors a problem that is continually encountered is this cross-cut. In nature, this situation looks normal, but photographically it is a disaster, the edited cuts creating a sensation of not matching (one character being in shadow, the other in sun).

The typical solution is to light the face of the back-lit character, giving him the same relative luminosity as the front-lit character. The drawback to this is that now the sky behind the back-lit character is white (overexposed) and the sky behind the front-lit character is blue. (Unless of course, you over-light the back-lit character for exposure, which looks equally as horrible.)

Totally in contradiction to my realist preferences is the perfect solution, which I discovered by mistake in one of the scenes from the film Femmes au soleil (Women In The Sun).

What it amounted to was placing each of the actors against the sun for the cross-cut shots, taking caution to ensure that the eye-line and direction of the actor’s look were correct. In this way, each face and each background had exactly the same luminous value, and the edited cross-cuts came without shock.

Of course, the geography was totally to our advantage. The land was all flat and covered with the same wheat in all directions.

When there was a geographic restriction, we would shoot one character in the morning and the other in the afternoon, after the sun had come around to the other side of the sky.

Two people facing each other, each back-lit; two suns on the planet Earth — and I don’t think anyone was the wiser.

If during the day scenes, a very careful moviegoer can count two suns, in the sunset scenes, he will not be able to count even one. I believe this is precisely what called unconscious attention to the light in Days of Heaven.

Generally speaking, the most beautiful moments of light in nature are in extreme situations; those moments when you think you cannot shoot anymore; when every photographic manual advises you not to try.

Malick wanted a major portion of the film photographed during one of these extreme situations, a period of time he called “the magic hour”. The time between when the sun has set and the fall of night—when the light seems to come from nowhere; from a magic place. It is a time of extraordinary beauty.

Actually, the time between sunset and total darkness is only about twenty minutes, so the term “magic hour” is an optimistic euphemism.

Malick’s decision to shoot so much of the film in this light was not simply gratuitous aesthetics. Historically and in story context, this was the period when these scenes would really have occurred, for the field workers would rise before the sun and work until it set. Their only “free” time being this “magic hour.”

Because of the talented intuition and daring of Malick, these sequences are the most interesting scenes in the film — “daring” because it is not an easy task to make all-Hollywood technicians understand that we would only shoot for 20 minutes a day.

To be as prepared as possible we would rehearse the scenes with the camera and the actors during the day. And then, with everyone poised and ready, as soon as the sun had set, we would shoot as quickly as possible — even frantically—fearful of even wasting a minute.

Everyday Malick would be like Joshua in the Bible, wishing he could stop the inexorable running of the sun.

And yet, some days, because of the length of the sequences, we would be unable to finish before darkness engulfed all. We were forced to complete these scenes on the following day, waiting again for the “magic hour.”

“Magic hour” scenes were always forced one-stop, to ASA 200. As the light waned, the lens was opened wider and wider, until finally we would use our fastest lens, the 55mm, opened to its maximum aperture, T/1.1.

Next we would pull the 85 filter, gaining what I consider in this situation the equivalent of nearly a full stop.

As a last resort, we would reduce the shutter speed and shoot at 12, then 8 frames per second, careful to instruct the actors to move very slowly so their movements would appear “normal” when the film was projected at the normal projection rate of 24 frames per second.

Dropping from 24 to 8 frames per second, we effectively increased our exposure time from 1/50 of a second to 1/16, gaining a stop and a half.

Shooting with this last breath of light meant the negative would have different tones, almost mutations, and these would increase in variation the deeper we shot into the “magic hour.”

MGM was the laboratory that took these unmatched variations and harmonized and timed them into a smooth, consistent flow. Bob McMillan was given screen credit as color consultant, and the results of his work are miraculous.

Often the rushes and rough cuts seemed like patchwork because of the color differences. His work unified it all and, unquestionably, I am very indebted to him.

Other than the sequences mentioned, the film was shot without artificial or supplemental light. When light was needed, we made every effort to make it appear natural and to justify its source.

To this extent, even our night interiors in the house were “illuminated” by the small electric table lamps of the time.

These lamps were on dimmers that reduced the color temperature of the light bulbs from their modern brilliance to a more appropriate warm, low-wattage appearance of original tungsten filaments. Soft lights were the only supplemental lights used for these scenes.

Our day interiors were photographed without any supplemental or fill lighting. We shot only with the natural light that was coming through the window. It was like photographing a Vermeer.

I had already had experience with this technique on other films, especially the French-German production Die Marquise von O..., (The Marquise of O) by Eric Rohmer.

With Terry, however, we added absolutely nothing. The result was, frankly, that the backgrounds are in darkness. Only the characters stand out as exposed.

The technical advantage to this, besides the extraordinary beauty and quality of pure natural light, was the freedom given to the actors from glaring lights and the asphyxiating heat from artificial lights — not to mention the lost time running cable, bringing in equipment, and adjusting lights.

The negative aspect is the shallow depth of field. With the lens wide open, the depth of field is at an absolute minimum. Fortunately, Malick is a unique director, and he readily understands and knows photographic techniques and restrictions.

Any other director would not have taken into consideration the lack of depth of field; at least, he would not have accepted it so readily and designed the blocking so the actors were always on the same focal plane, (i.e., no over-the-shoulders or foreground vs. background placement that would have made one actor out of focus).

Our creative effort was always aimed at simplification. Again, like the great silent filmmakers, we used fundamental illusions or tricks that were done simply, quickly, effectively, and — contrary to today’s tendency — always in the camera.

Audiences have learned a lot over the years (if not consciously, then at least subconsciously). An audience recognizes immediately when there is an optical trick because the grain of the film becomes noticeable and the color tones shift. To avoid this optical stage for our special visual effects, we kept everything in the camera.

From my European experience, I brought a technique, my camera crew, at first considered a sacrilege, the in-camera fade.

At the end of some scenes, we would fade to black by closing the lens stop slowly. For instance, if our exposure was an F/2.8, we would fade slowly to an F/16, and then close the variable shutter on the Panaflex until we achieved total black.

Another technique we utilized was a stylized method of shooting “day-for-night.” During the years of black-and-white, “day-for-night” was a way of shooting wide exteriors during the day and making them appear as though they were night scenes. (Interestingly, in Europe this technique is known as “American Night,” a semantic acknowledgment of its origins.)

The standard black-and-white method that is used even with color today is to underexpose the scene and print down in the positive print. The main difference with black and white was the use of a red filter that added luminosity to faces, added overall contrast, and, most importantly, darkened the sky.

In color, to affect the sky and the contrast, polarizing filters or graded neutral-density filters are used. I find both these methods unsatisfactory.

For Days of Heaven, we simply avoided the sky by elevating the camera and shooting down, or by choosing spots where the horizon was not visible — such as at the foot of a mountain. To accentuate the night effect, besides the standard underexposure and printing down, we also pulled the 85 filter and placed the actors so that they were backlit.

The result was an intense cold, blueish moonlight — a supplementary advantage of shooting in color.

Throughout the production of Days of Heaven, Terry created an atmosphere and space for improvisation, enabling us to take advantage of each moment.

His striking understanding of cinematographic techniques and his continued artistic encouragement and support were, more than anything else, responsible for the visual achievements we obtained.

When the plague of locusts descends on the fields of wheat, Terry’s atmosphere of daring and essential simplicity made me suggest a simple technique that would allow us to maintain optimum image quality (without resorting to an optical), and allow us to obtain the maximum dramatic effect.

For our foreground, we used live locusts supplied to us by the Canadian Department of Agriculture, but for the wide panoramics, silhouetted tractors and blackened workers, we used a technique used in The Good Earth: running the camera in reverse and dropping peanut shells from helicopters.

When the film was projected forward, the “locusts” would appear to be flying up. Of course, this meant everything had to act or perform in reverse, specifically the actors and the tractors.

Virtually everyone said “No, it will never work.” But the few believers convinced them to let us try — again, special thanks to Terry’s daring. And when they saw the rushes, they were astounded. It worked perfectly.

All because of Malick. Truly one of America’s finest filmmakers, a man of universal culture.

In cinematographic terms, he belongs to the same artistic family as Rohmer and Truffaut. A man whose daring and artistic talent encouraged me and complimented my photography. He made it easy for me to adapt myself to my new work on the new continent. The days we worked together were, indeed, Days of Heaven.

In addition to the 1979 Oscar for Best Cinematography, Days of Heaven also received nominations for Best Original Score and Best Sound, and Patricia Norris got the first of her six Academy Award Nominations for Best Costume.

Almendros would later be invited to join the ASC, as were John Bailey, Eric Van Haren Noman and Paul Ryan.

Almendros would go on to shoot such films as Kramer vs. Kramer (1979), The Blue Lagoon (1980) and Sophie’s Choice (1982) — all of which earned him additional Academy Award nominations — before he died in 1992 at the age of 61.

Bailey later spoke with The Criterion Collection about working on Days of Heaven and his collaboration with Almendros: