Nothing But A Man: A Movie for All Seasons

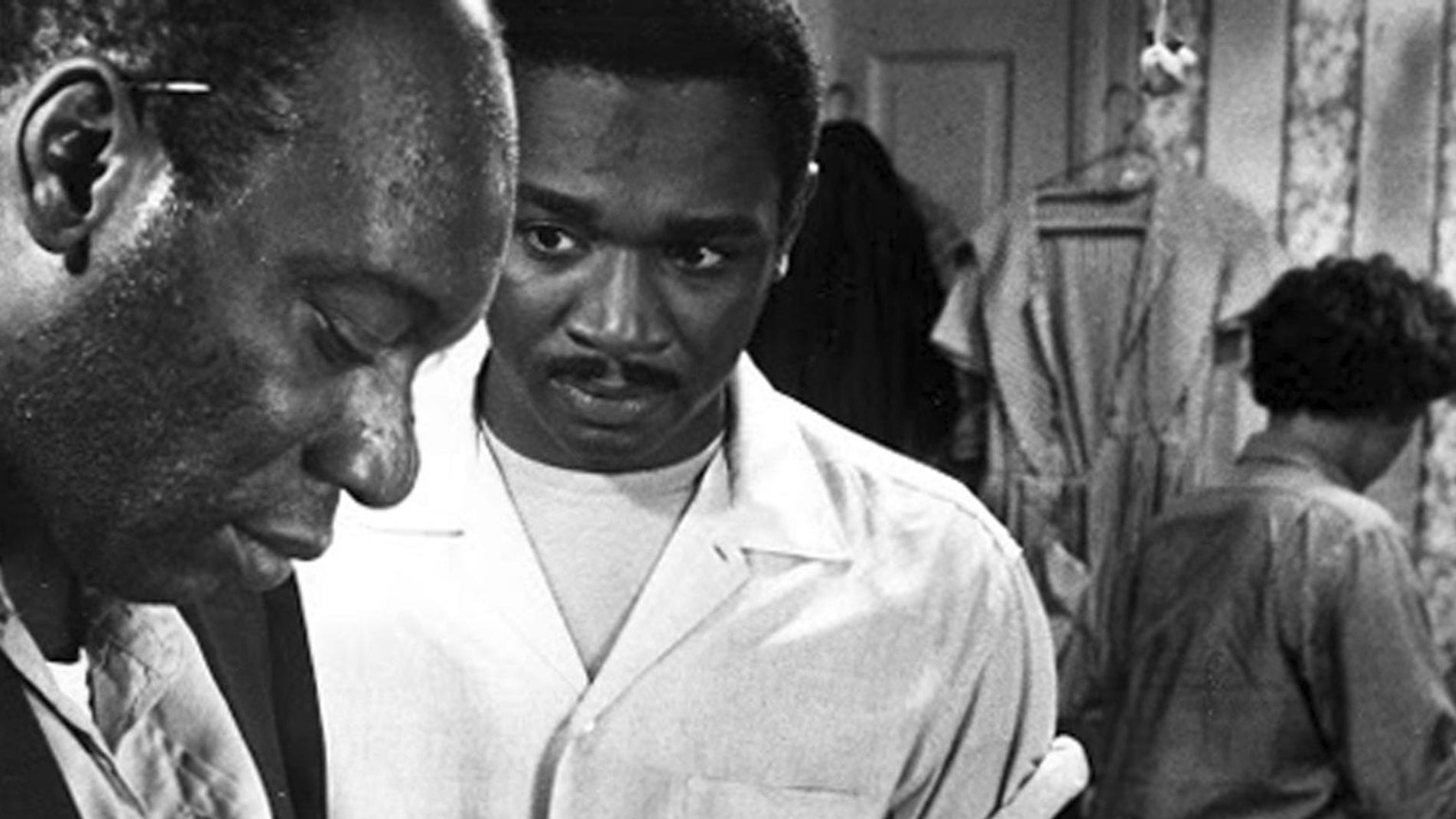

When it premiered in 2013 at London’s Southbank Centre, the American racial drama Nothing But A Man was a critical sensation. But this still little-known landmark film was made more than 55 years ago, shot in the heart of the South in the early 1960s by director Michael Roemer and cinematographer Robert M. Young.

When it opened in September 2013 at London’s Southbank Centre, the American racial drama Nothing But A Man, set in and around Birmingham, Ala., in the early 1960s, was a critical sensation. The film tells the story of a young, black railroad worker as he and his friends, who live in a railroad car, deal with their limited horizons. Duff (Ivan Dixon) bristles at having to depend on the uncertain and racist whims of white foremen and bosses for work. He fights to break out, just to be a man, unbending in his sense of self. He marries an educated woman, Josie (played by jazz vocalist and Civil Rights activist Abbey Lincoln in her movie debut). Josie is, by Duff’s own admission, above his social standing; she is the daughter of a black minister who disapproves of Duff’s pride. After multiple setbacks, the couple faces an uncertain future — further complicated by Josie’s pregnancy.

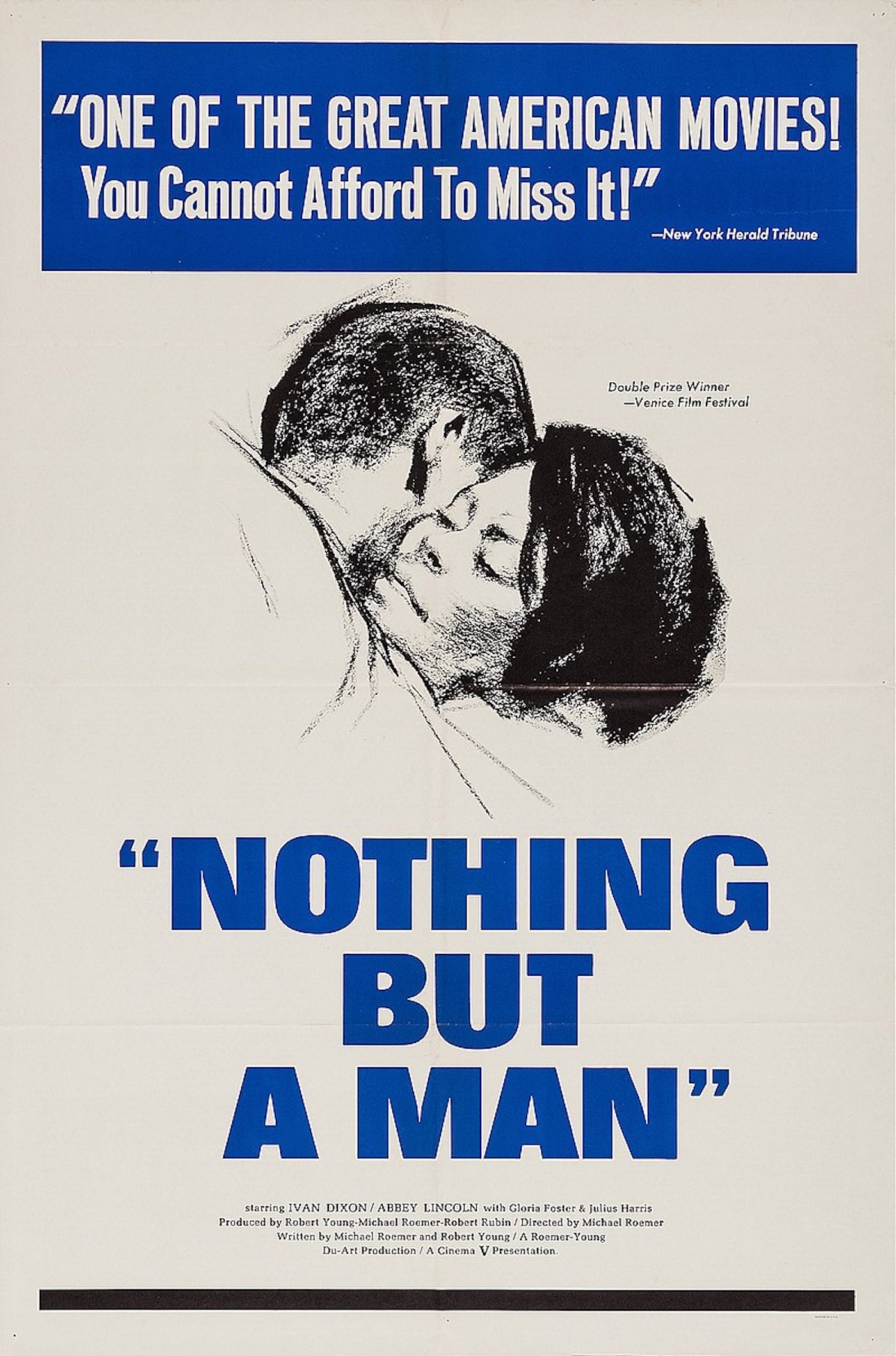

Nothing But A Man is not a contemporary film casting a rearview look at the struggles of African-American men and women during the Civil Rights era. It carries not a whit of nostalgia, nor a whit of expiated guilt by its two white screenwriters. From where we stand now, in a newly aroused sense of Black Lives Matter, confronting the ugly racial history documented in the New York Times’ 1619 project, Nothing But A Man has the immediacy of this summer. But this still little-known film was made more than 55 years ago, in 1964; it won several awards at that year’s Venice Film Festival. The American premiere was a few weeks later, on Sept. 19, at the New York Film Festival. The movie subsequently received a negligible indie-circuit release and disappeared, re-emerging in 1993 when it was selected for the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress. That honor sparked a theatrical rerelease, mostly in arthouses. Roger Ebert gave it a glowing review, noting that it was “a film more famous than familiar.” A limited video release followed. It’s almost impossible to find today, even on streaming outlets. As I write this, the only listing I can find is a single copy of the 40th anniversary DVD — priced at $270.

Incredibly, the 2013 release in London was the film’s English premiere.

Nothing But A Man was co-written by the director, Michael Roemer, and the cinematographer, Robert M. Young. They were classmates at Harvard, graduating in the class of 1949. Roemer was born in Berlin in 1928. At age 11, shortly before Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, he was one of nearly 10,000 mostly Jewish children who were sent to British foster homes in the Kindertransport program. In the U.S., Roemer found in American blacks a history analogous to the centuries-long persecution of his own people in Europe.

Robert M. Young’s father was Al Young, the founder of New York’s famous film laboratory, DuArt. Founded in 1922, DuArt was home to legions of independent, documentary and experimental filmmakers. Several years ago, when DuArt cleared out the unclaimed negatives and print elements that had been stored on site for decades, filmmakers and film archives, including the Academy Film Archive, were gifted with hundreds of nearly forgotten movies. Fortunately, Roemer’s film was not one of the nearly lost.

Nothing But A Man was Young’s first feature credit. About a decade later, he directed his own first feature, Short Eyes, closely followed by Alhambrista, which won the Camera d’Or at the 1978 Cannes Film Festival. A few years before shooting Nothing But A Man, Young had filmed in the South on an NBC documentary titled Sit-In, which won a Peabody Award.

Young and Roemer decided to do research for their script by taking a reverse Underground Railroad road trip, driving into the heart of the South. The sense of “place” of small-town Alabama permeates the visuals of the film.

Here is the trailer:

Nothing But A Man was photographed in 35mm black and white in the classic 1.37 Academy aspect ratio rather than the ubiquitous 1:85. The aspect ratio mirrors most of the 16mm cinema verité documentaries of the time, but Young’s cinematography is anything but verité. Critics have cited Italian neorealism as the film’s visual influence. What is most striking about the cinematography, it seems to me, is its crafted professionalism in lighting, composition and shot selection.

It honors some of classic American studio cinematography while embracing the advances of 1960s lightweight reflex cameras, enabling intimate imagery in practical locations rather than studio sets. You can compare the open style of this film with two great black-and-white studio films shot in the anamorphic format just a few years earlier: The Hustler and Hud. Both won Academy Awards for their cinematographers, Eugen Schüfftan and James Wong Howe, respectively.

An unexpected element in Roemer’s film is the use of early 1960s pop songs on the soundtrack — two decades before the ground-breaking use of Motown hits in The Big Chill. In fact, Nothing But A Man marked the first licensed use of Motown hits in a movie, featuring songs by Stevie Wonder, The Miracles, Martha and the Vandellas and Mary Wells. The rights are reported to have been acquired for $5,000, a steal even then.

Abbey Lincoln was no gilded pop-jazz celebrity. Her music reflected urgent themes of the fight for racial freedom. During this time, she was married to percussionist and fellow activist Max Roach. In this clip, Lincoln sings “Driva Man,” the first of the five tracks from Roach’s Freedom Now Suite. The video is from Belgian television and was made the same year Nothing But A Man was released. Tenor saxophonist Clifford Jordan plays second solo to Lincoln. (The original vinyl recording featured Coleman Hawkins.)

Another footnote is that the novelization of Roemer and Young’s screenplay was published six years after the film’s release. The unlikely choice to write it was hard-boiled crime novelist Jim Thompson.

I confess that I did not see Nothing But A Man at the time of its release, its rerelease or its British release, nor did I see it on DVD. I saw it this summer, when it was shown on TCM on July 19. I have been in its thrall since, wondering how such an important film flew “under the radar” of so many of us for so long. (I write “us” because I am hardly alone in this lapse.)

Metrograph’s website features a recent, in-depth interview with Roemer by Melissa Lyde. Photographer Nan Goldin included Nothing But A Man in Metrograph’s online film series “Nan Goldin Selects.”

I have no idea what the future holds for this landmark film, but I decided to write about it not only because of my great admiration for it, but also because you can actually find it (at least for now) in good resolution on YouTube, where it was posted three years ago. There’s no way to know how long it may stand, so I urge you to watch it right now, as I know of no other way to see it. Let’s hope one of our beloved DVD companies such as Milestone or The Criterion Collection will soon make it available to us.