Creating Mechanical Models and Miniatures for The Spy Who Loved Me

A giant submarine-swallowing supertanker, a rocketing motorcycle sidecar, an automobile that converts to a miniature submarine — all taken in stride by this creator of magic for the James Bond films.

By Derek Meddings

(EDITOR’S NOTE: The author, winner of the UNIATEC Grand Prix for his use of mechanical models and miniatures in the special effects of the latest James Bond film, The Spy Who Loved Me, has been working at his specialty for the past 25 years. His artistry is currently being displayed worldwide in Superman, and he is hard at work on the spectacular effects for the upcoming new James Bond film, Moonraker.)

When we, as special effects technicians, receive a script we read it and then panic, because straight away we know that we have got terrible problems and that they will be expecting us to come up with all sorts of miracles.

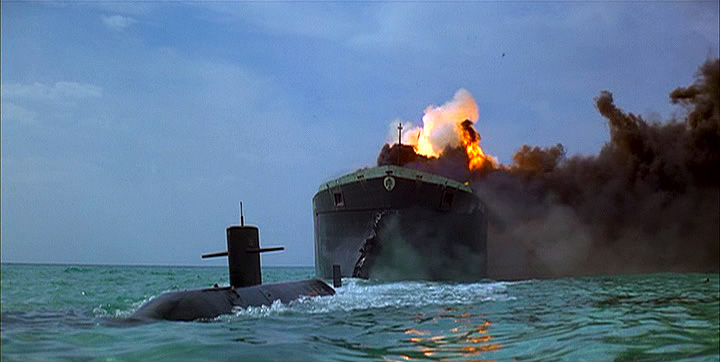

On The Spy Who Loved Me, the main problems that we had involved dealing with situations that included water and an oil tanker. As every special-effects man knows, as soon as you get a shot that involves water you are in trouble because no matter what you do, you can never scale the water to the ship. If you were going to build the craft full-size you would be all right, but you know you can’t afford that, so you have to work it out in such a way that eventually you will be able to convince audiences that they are looking at a full-size vessel.

For this picture, we were asked to go and see the Shell people, because from the start the director, Lewis Gilbert, wanted to use a real supertanker. We said that we would build it as a miniature, but Lewis was a little doubtful as to whether it would look convincing enough.

We went to a meeting with the representatives of the Shell Company. I sat there very quietly because I knew that I was going to have to explain what we wanted to do with their tanker. They were talking about a tanker that was now in a French port and was de-gassed and had been cleaned out, with the possibility that we would be able to use it. So I thought, “That gets us out of a problem. We will use the full-size tanker.” Then they said, “What would you like to do with it?” I said, “We need to see it at sea several times and eventually we will want to do explosions on the deck.”

Everything went very quiet. They thanked us very much for coming and talking to them and we didn’t hear any more. They seemed to lose interest all of a sudden. Also, of course, there was the fact that we would have to ensure the tanker while we were using it. When we heard what the figure for the insurance would be, that certainly put a real tanker out of the picture altogether. So, it was decided that we would build a miniature at Pinewood Studios (England).

The way we had to approach the problem was complicated by the fact that we had to have three submarines being gobbled up by the tanker. We knew that the submarines would be difficult, because nuclear submarines are huge black tubes with very little detail, unlike the conventional submarines with bits and pieces sticking out all over them. This meant they would have to be built to a good scale to look believable. So I worked out what I thought would be a good size for a submarine and then scaled the tanker to the submarines. The tanker you see in the picture turned out to be 63' in length.

British Film Producers Association.

We had to build the tanker so that the bows would open and a submarine would be taken inside by the tanker driving over it. We did this by building only the last 10' or 15' of the tanker as a boat; the rest was like a catamaran. If you looked underneath you would find that it was bottomless, so that when we opened the doors hydraulically, the tanker could drive over the submarines without any restriction whatsoever.

Until Lewis saw the shots of the miniature tanker at sea, I know he still thought we should do some shots on the real tanker at sea and intercut it with the miniature to take the curse off the miniature. However, by the time we had finished the model tanker and built all the things into it to create the bow wave and water disturbance that is caused by a vessel of that size at sea, and shot it from several different angles, he was totally convinced, and throughout the whole picture, only the miniature was used.

The tanker had a crew of three and was a very maneuverable boat. In the final part of the picture, the tanker is set afire by explosions going off along the full length of it and finally, it sinks. Before actually blowing it up and sinking it, we stripped it of its very expensive Evinrude outboard engine and various pumps in the flotation chambers along the sides of the front part of the tanker. This was done because we discovered, after our first sea trial, that it had a tendency to nose dive because of the high speed it had to attain. Otherwise, it gave the impression of hardly moving when filmed at high speed. The flotation chambers would then be flooded to assist in sinking the tanker.

These chambers had given us a lot of trouble even though the front part was empty. There was still not a lot of space because of the room needed for the submarines to enter, so the chambers were long and narrow with open tops for quick filling. Even when filled we found that it would only sink to the level of the deck, so Peter Lamont (the art director) started to make cement blocks with rings set into them so I could hang them inside this bottomless boat. As always, when filming this type of sequence, some things work for you and others don’t. You buiId a boat to float and to sink; it wants to sink when it should float, and float when the darn thing should sink! When I approached the boatbuilding yards about this, they said, “We don’t know anything about sinking boats; our customers want them to float!”

Although most things had been worked out, you could sink the tanker only once. Even though I did have a scheme for getting it to the surface and filming it again if it wasn’t right the first time, thank the Lord we didn’t have to do it.

When we came to the car situations, again we intended to do this with models, but as the picture progressed and we got involved with the people who make Lotus cars, they were so helpful that we thought it was quite possible that we could use one of their full-size cars in the water. Altogether Lotus provided us with six body shells of their latest Esprit car, which had to do varying things. The wheels had to retract inside the car and the wheel arches fold over to convert it from a car into a very smooth-looking submersible. We started off by thinking we could fit most things into maybe two cars, but we had so many things happening with the wheels and the fins — firing rockets out through the back windshield and firing missiles from the front of the car — that we found it was easier to have several vehicles and use them to build in the requirements that we needed — plus one that was totally submersible traveling underwater.

Esprit automobile furnished to the filmmakers by the car’s manufacturer for action sequences in The Spy Who Loved Me. In addition, miniatures of various sizes were

employed to film the extremely intricate sequence.

The design of the screens on the car was very cunningly done because Ken Adam, the production designer, and I decided that if we actually blotted out the windscreen and the side windows with louvers we wouldn’t have to show who was sitting inside. We knew that eventually, we were going to have to have divers inside driving it.

When it started out, they tried to use re-breathers because we didn’t want bubbles coming up from the car, but this became a little difficult because there are certain dangers in using re-breathing outfits. After our first few days of rushes, we realized that it looked better to have some bubbles coming from various parts of the car. It just seemed to enhance the shots, so the divers were told to forget their re-breathing apparatus and we would use normal diving equipment which made it a lot easier for them. In spite of the full-size Lotus cars, we still had to use miniature one-quarter-scale cars for certain shots in the picture. The first time you see the car underwater it is miniature.

All the shots you’ve seen were shot at sea in the Bahamas and this presented us with problems because we were working in shark-infested waters. If you’re a coward it’s the usual thing, when you go anywhere, to enquire into the sort of things that swim around in the water. They said, “You know, we’ve got a lot of sharks, but you don’t see them often.” I thought, “Yes, we’ve heard that before somewhere. Just wait until we get the camera out and get into the sea; they’ll arrive in schools.” As it happened, we saw only two. One was a nurse shark and the other a 12' hammerhead which we hooked on a line at seven one morning. I thought of lots of good reasons for not going in the water that day.

The sequence in which the helicopter chases Bond off the jetty in his Lotus car was shot in Sardinia, Italy, in sunny weather, so it was decided to film all of the miniatures in the Bahamas in order to match that weather.

The helicopters were large radio-controlled models which had to explode and crash into the sea. One of them Bond shoots down with a missile fired from underwater after it has chased him into the water. The director asked me if we could get a shot of the helicopter from underwater, with the camera looking up and seeing the shape of the helicopter hovering just above the water.

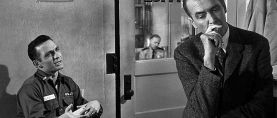

We were shooting the Lotus car underwater sequence when I got the message that the surface was just right for that shot, so we thought we would try to get a test shot to see how it looked. We hung the helicopter on a cable from the crane and suspended it just above the surface. From the moment we hung the thing on the crane the weather changed from calm to windy and a choppy sea. Lamar Boren (cameraman) and I went down but had terrible difficulty seeing the helicopter through the water because we were being washed around by sea swells. Every so often I would spot it and Lamar wouldn’t. It was very difficult looking through the viewfinder in rough conditions. I would give Lamar a prod and point up. Lamar would stick the camera upwards and shoot. When we surfaced we knew it was useless unless the conditions were perfect. Anyway, we had it printed as a test. It went into the picture. The fleeting glances you got of the helicopter were just what the director wanted.

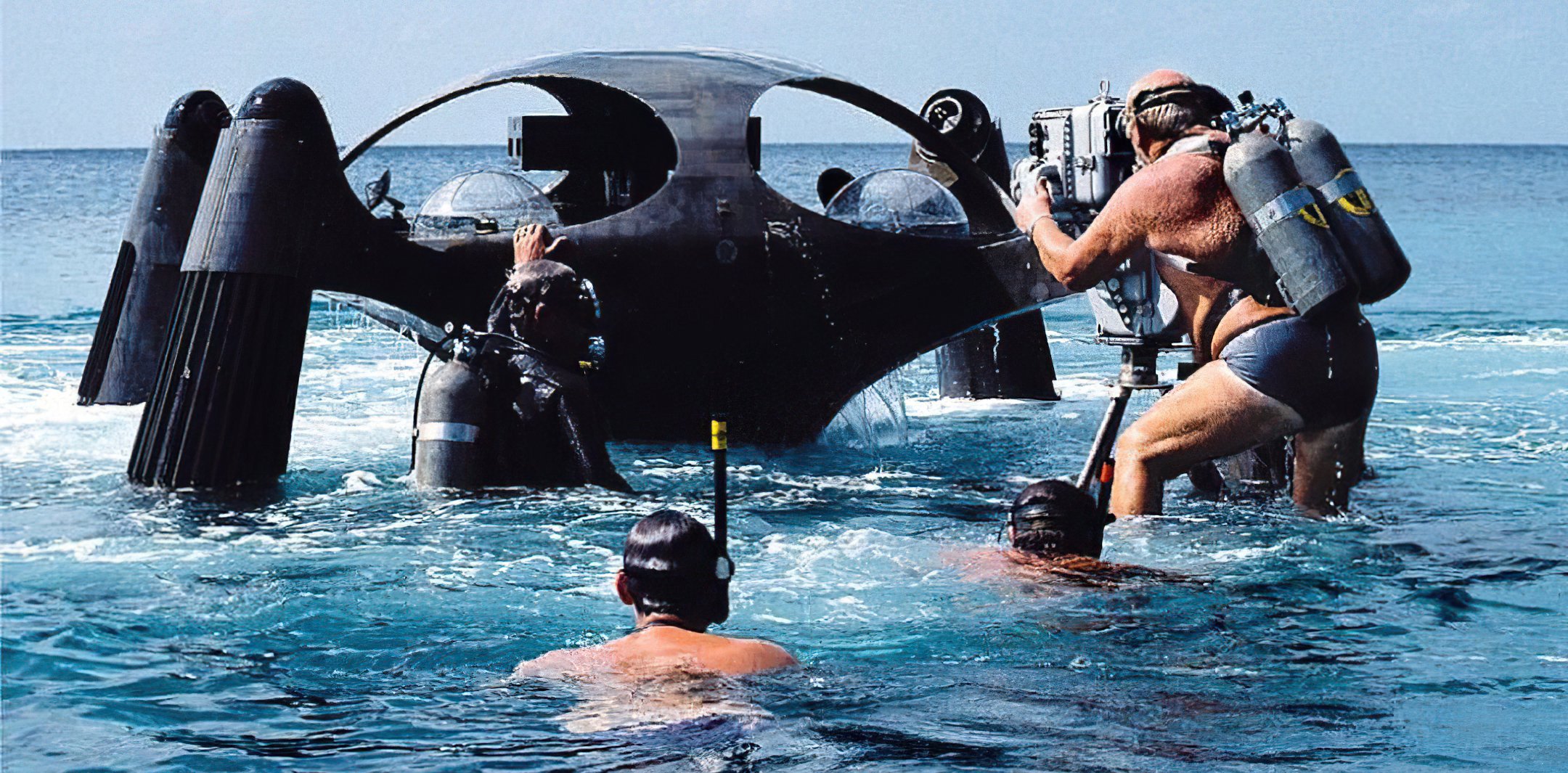

We had a large crew from Pinewood — riggers, carpenters and plasterers — working 50' down, despite the fact that most of them had never dived in their lives. The deepest that any of the crew had ever been down was 20'! They had to rig up tracks on the seabed. We had to build dollies that could track into the various models including a four-foot model of the Lotus car for the sequence where it went in between two rocks and when it approached Atlantis. Atlantis was that monster you saw standing like a big spider which Bond and Anya found.

To build this full-size would have been an enormous undertaking, so we used a large miniature, which meant that we had to scale the car down to quarter-size and still have it maneuverable to use when it approached Atlantis.

We had to have the model of Atlantis coming out of the sea slowly. In order to do this, we built a hydraulically-operated rig which we could put about 20' down and then operate it to bring it up out of the water. We ended up with problems. For example, by the time we got it set up in the right depth of water, the tide would turn, the sea level would drop and then we would have to rearrange the rig and tow it a little farther out. It was very important that it came out of the water at the right height and towered above you, in order to give the impression of size.

I think the model shots in The Spy Who Loved Me were an achievement because producers and directors always have this thing about miniatures in their minds. They remember the worst model shots they have ever seen and somehow cannot get it out of their minds that the same thing is going to happen to their picture and that they are going to end up with a good picture and terrible miniature shots.

We are currently in a period when pictures are becoming more ambitious and people are dreaming up all sorts of shots where there will be no possible way to get the desired effects other than through the use of miniatures. If you are going to do something like a James Bond film, for example, it’s certain that you are going to be involved in miniature shots somewhere along the line.