Mad-Dog Englishman: The Limey

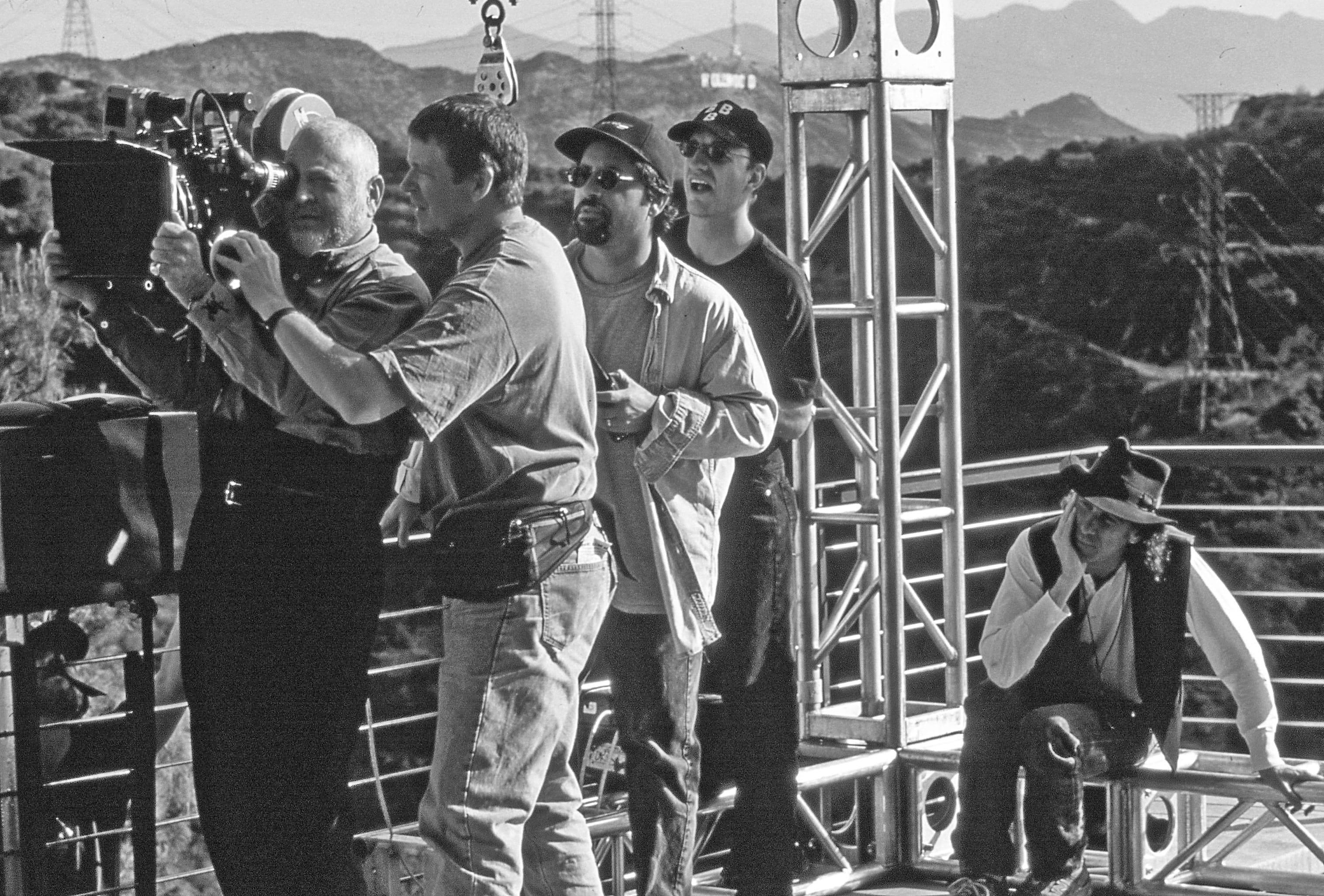

Director of photography Edward Lachman, ASC arms this inventive thriller with an impressive visual edge.

Unit photography by Bob Marshak

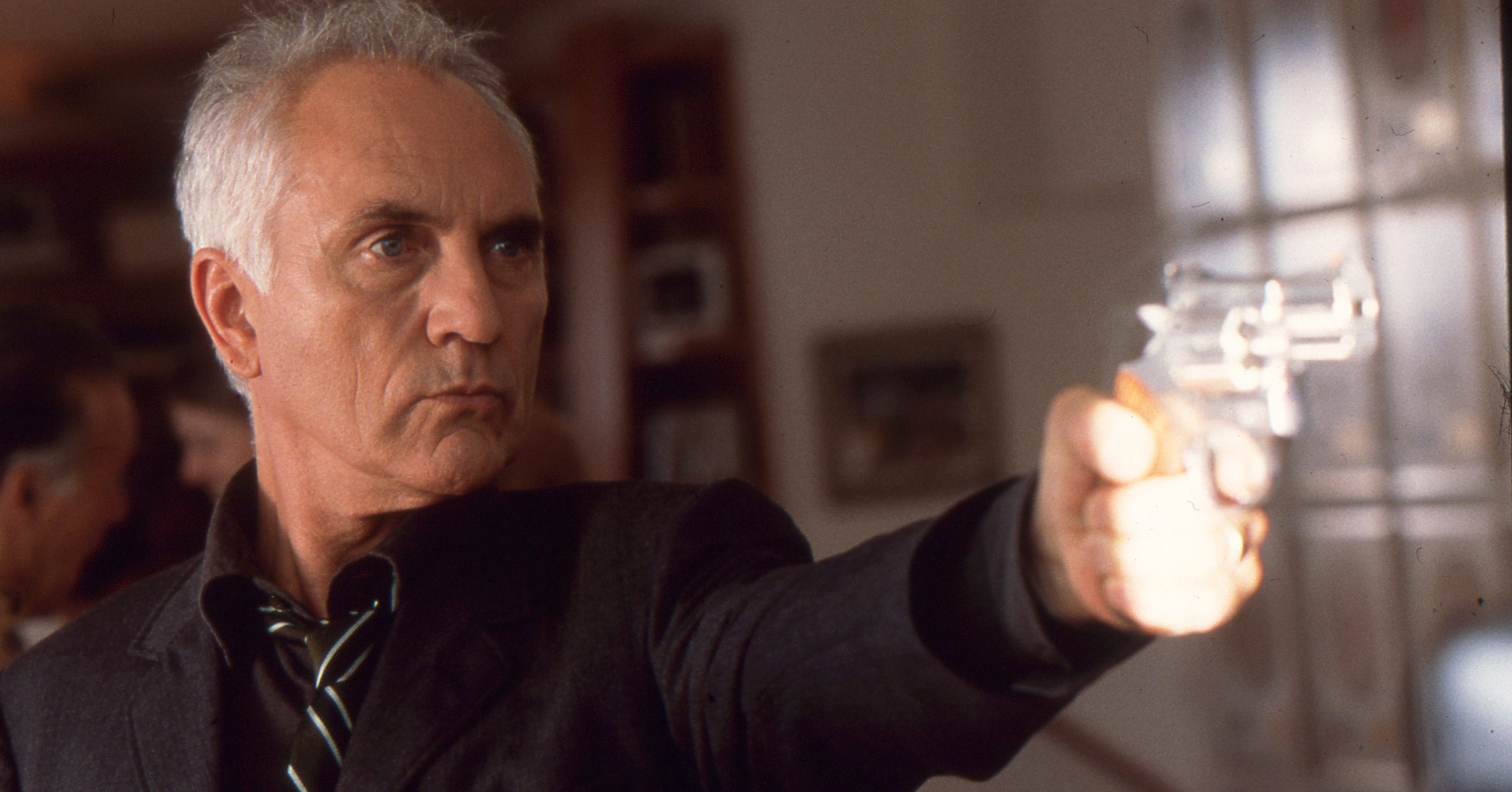

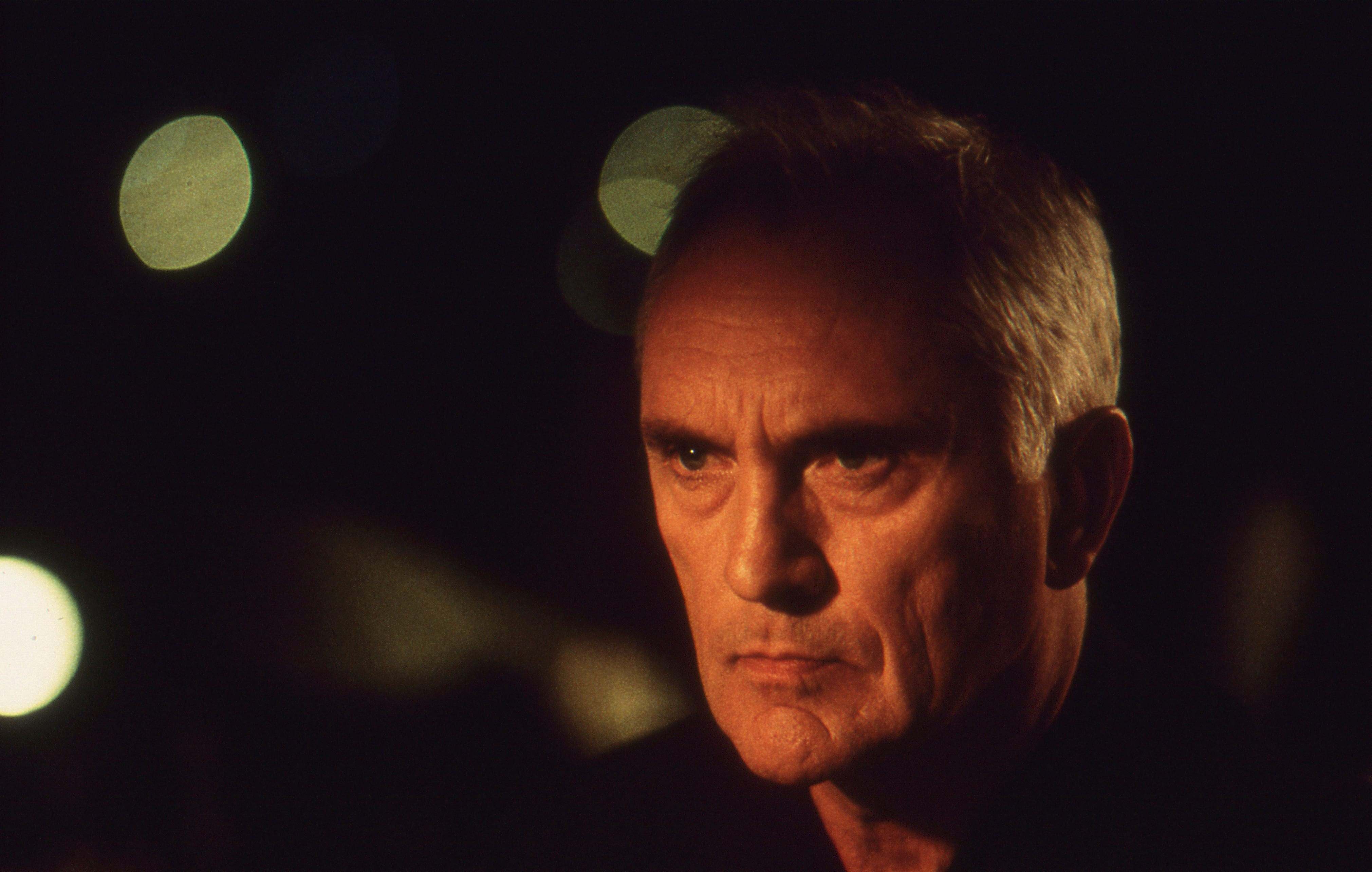

In The Limey, a British career criminal named Wilson (Terence Stamp) arrives in Los Angeles to avenge the mysterious death of his daughter, Jenny (Melissa George). Recently released from his latest stint in prison, this no nonsense bloke has few leads, but quickly finds trouble in the form of a drug-money-laundering operation fronted by corrupt recording impresario Terry Valentine (Peter Fonda), who was romancing Jenny at the time of her demise. Immediately unwelcome, Wilson is met with plenty of grievous bodily injury at the hands of Valentine’s bodyguards — but doles out his own brand of brutal vengeance when necessary.

Written by Lem Dobbs (Kafka) and directed by Steven Soderbergh (sex, lies and videotape; Kafka; Out of Sight), The Limey is a vivid piece of pulp fiction that features an inventive non-linear storytelling approach and expert cinematography by Edward Lachman, ASC.

Lachman studied fine art in Paris, and learned his craft while doing documentary and feature work with such directors as Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog and Wim Wenders, and later assisted and operated for such cinematographers as Sven Nykvist, ASC, Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC and Robby Müller, NSC.

Based in New York City for the early part of his career, Lachman compiled a diverse list of feature credits, including The Lords of Flathush, Union City, Desperately Seeking Susan (see AC July 1985), True Stories (which earned him an Independent Spirit Award nomination), Less Than Zero, Making Mr. Right, Mississippi Masala, Light Sleeper (another Spirit Award nomination), London Kills Me, My New Gun, Touch, Mi Familia, Selena (AC May ’97) and Why Do Fools Fall in Love?. The cinematographer recently completed the Universal Pictures drama Erin Brockovich, also directed by Soderbergh, which stars Albert Finney and Julia Roberts.

Introducing The Limey for a packed cast-and-crew screening held at the DGA Theater last March, Soderbergh described the picture as “one of the fastest films I’ve made, and one of my best experiences.” Asked how the speed of the production impacted his contribution to the film, Lachman replies, “Principal photography took about 32 days. Again, when you’re forced into certain shooting situations — such as sometimes using just available light — you have to cover the action in a more expedient way. We often shot with two cameras, shooting in one direction and then quickly moving into another. I’d done that before, on London Kills Me and parts of Selena, and I think it helps the energy for the acting. In this case, it gave Steven more freedom to deal with the actors, because the performances dictated what the cameras were doing, instead of the other way around. Working that way also gave the actors much more of a feeling of performing in real time and with each other, because the action wasn’t being cut up into so many pieces. It also helped keep up the momentum of shooting, because we could cover two angles from each direction with each take, which helped matching in the editing process, especially when there was any improvisation.

“The hardest part of shooting that way is keeping focus, so I had the camera assistant use a sort of ‘zone’ system in which we laid out a series marks around the area where the actors would be, rather than setting specific marks for them to hit.”

The cinematographer notes, “Although he had full backing from Artisan Entertainment, Steven wanted to keep The Limey within the realm of a smaller-sized independent film. We studied and discussed how independent films from both Europe and the U.S. were made in the 1970s, [focusing on films] such as Bob Rafelson’s Five Easy Pieces.

“What we found was a much more freewheeling, pick-up-the-camera-and-shoot feel, which contributed to our shooting in a much looser way. About 80 to 90 percent of The Limey was done handheld, even though one may not always notice that it is handheld. Only about five percent or less was done with a tripod. If the camera could instead be put on a table or chair, we’d do that. We made a series of these pads we called ‘Tootsie rolls,’ using rolled-up sound blankets to cushion and position the camera on these surfaces. We even used them to pan the camera sometimes, just sliding them along a flat surface.”

Lachman used Moviecam Compacts on The Limey, generally fitted with his personal set of Series II and III Cooke Speed Panchro primes. “Those lenses were made 30 years ago, which contributed to the look of the film,” the cinematographer attests. “The Cookes don’t have the contrast, definition, or multi-coatings that a modern lens like a Primo has. They’re softer and more forgiving, so we didn’t use any diffusion. Steven also liked the lens flares we’d sometimes get with them. At night, though, I’d use Zeiss Superspeeds.

“We did everything possible to demystify the process of shooting, and do without all the equipment, camera gear and lights that many people think they have to have these days. We asked ourselves, ‘How can we approach this film if we don’t have all those things?’ That created another kind of aesthetic that could be applied to the storytelling approach, and it was so successful for us that we shot Erin Brockovich the same way — and that was a $55-million studio picture.

“In terms of the crew, I was fortunate to have my preferred team — the same gaffer I always work with, John DeBlau, the same first assistant, Mike Hall, and a very good operator, Ray de la Motte, who was very familiar with how films were shot in the 1970s and innovative about how we could do certain things.

“Steven also cast The Limey with icons of the ’70s, which is an interesting extension of what we were trying to do with the cinematography. It became thematically intriguing.”

Added to this stripped-down production approach was an unconventional narrative style that makes use of both flashbacks and flashforwards, which inform the audience where certain characters are from, and also hint at where they may be going. “We discussed different storytelling styles, and Steven wanted to suggest the characters’ interior world,” Lachman describes. “Film is able to show locations very easily, while in a novel it may take several paragraphs to describe the place and setting. But it’s much more difficult for a filmmaker to enter a character’s interior world than it is for a novelist.

“In Out of Sight, Steven experimented with this idea by using changes of voice and story perspective, which was something I’d also seen in films by the French director Alain Resnais. In The Limey, for instance, we’d shoot the same dialogue scene between Terence Stamp and Leslie Ann Warren in three different locations, and then Steven would cut this footage together as one continuous dialogue. He would then go one step further and run the dialogue over a reaction shot of the character who is supposed to be speaking. That breaks up the traditional narrative flow, and the audience gets an impression of the character’s interior world.

“In a sense, the footage we shot was treated almost like ‘found’ images. This editing plan was something that Steven was thinking about before we began shooting, and we discussed getting the coverage he needed, but it really came together in the editing room. This kind of manipulation of time and space is sometimes done in fantasy films like The Matrix, but not often in a real human drama.

In one recurring introspective sequence, we see a more youthful Wilson of 30 years ago as he serenades some gals with his guitar at a party. “He’s seen as a budding young criminal,” Lachman relates with a laugh, explaining that much of this footage was borrowed from the 1967 film Poor Cow, a Ken Loach picture about working-class loners in which Stamp starred as a character not coincidentally named Wilson. “I had to match the look of that footage for certain cutaways we needed as flashbacks, consisting of shots of Wilson’s daughter as a little girl,” Lachman says. “The difficult thing was that we didn’t have the footage from Poor Cow at that point, and I only saw it on VHS toward the end of our shoot. I therefore had to try to re-create that style based on that reference. I was pleasantly surprised that our footage matched as well as it did when we obtained the dupe negative to make our final print.

“We also needed material to suggest the present-day Wilson’s mental image of Jenny and her life leading up to her death, so we had to find a visual way to suggest that concept. What we ended up doing was throwing the shutter out of sync, which creates a vertical streaking effect in the footage, especially with strong highlights.

“I ended up using a strong Krypton-bulb flashlight, which we move across the actors’ faces and bodies to help create a creepy, interrogative effect. Clairmont Camera was very helpful in working with us to create the effect we were seeking.

With his nearly impenetrable English accent, the gruff Wilson “is very dislocated and misplaced,” Lachman says. “He’s never been out of East London, let’s say. He’s also been in prison for a number of years, so images of him needed to have that sense of being out of place and uncomfortable, and we tried to suggest that with the lighting. For example, in some scenes we’d use very intense lighting in certain areas, forcing Wilson to readjust himself because of the brightness.”

One example of this technique is a recurring shot in which the surly character meditates in his seat aboard an airliner bringing him to Los Angeles. While shooting on the aircraft interior set, “Steven wanted to continue with our naturalistic style by having the windows burning out and the light pouring in,” Lachman says. “To do that, we put an incredible amount of light into a eye that surrounded the set. We then had a complicated rig, consisting of three 20Ks on a crane arm, that simulated the way sunbeams move around inside a plane interior as the aircraft changes direction. We kept the lighting inside the plane very low, which allowed the eye to burn out and bleed a bit, and the 20Ks to project these very strong shafts inside at about four stops over key. Then, specifically on Terence Stamp, I bounced a 6K Par into a mirror and though his window to further burn out the left side of his face. That way, the light became an intrusion on him.” This pattern is repeated throughout the film, as the pasty Wilson visibly cringes from sunshine and bright sources.

The Limey trails Wilson though a spectrum of Southern California milieus, from the barrios of East L.A. and faceless suburbs of the San Fernando Valley to opulent mansions atop the smogen-shrouded Hollywood Hills and the majestic seaside cliffs of Big Sur. “Almost the entire film was shot on location,” notes Lachman, who adds that this approach directly influenced both his lighting plans and execution. “We weren’t trying to control the exteriors as much as I usually would, and we’d always try to continue with whatever lighting we found on the locations. For instance, in a fluorescent situation, we’d just light with fluorescents, and sometimes even add Plus Green or Full Green gel to them to make sure they looked like fluorescents.”

exterior of

Valentine's

seaside

mansion at Big

Sur was lit with

HMI balloons,

casting an

extreme blue

that contrasts

with the home's

warm interior

(created with

firelight

effects).

In one extended nighttime exterior scene, Wilson pays a call on his daughter’s friend Ed (Luis Guzman), who had notified him of Jennifer’s death. Seeking answers, Wilson also gains Ed’s confidence, and the unlikely pair begin their investigation. “In that scene, there’s this particular two-shot in which you can see the entire downtown cityscape of Los Angeles lit up in the background,” Lachman says. “When you work off of whatever light exists — and we were shooting wide open at T1.4 — you can get an interesting sense of depth, because sources far in the distance aren’t being overpowered. If you start shooting at T2.8 or a 4, you lose those backgrounds, so I always tried to light off of what I found on the location, so our perceived set would be much greater than what I could actually light. I know that cameramen like John Seale [ASC, ACS] and Chris Menges [BSC] sometimes do that as well. You can get a very different look when you light that way, and it’s not just in terms of depth of field. You pick up ambient light, color temperatures and subtleties in the shadows that you wouldn’t get if you tried to light the entire scene yourself.”

Aiding Lachman on this and other nighttime scenes was Kodak’s Vision 800T 5289 film stock, which had just been introduced before he began shooting. “I’d done some tests with the 89 and the Vision Premier 2393 print film, and I thought the combination was sensational. It was my standard test, just using a face against a neutral-gray backdrop and bracketing exposures in half-stop increments. And while the 89 is slightly grainier than Vision [500T] 5279, it didn’t bother me.

“A lot of people have been questioning the Vision print stocks because they think they’re too contrasty, but I think it’s just how you use them. I generally light with big, soft sources, so I welcome the contrast, but I suppose it would be more unforgiving for anyone who uses harder light.

a seedy bar, a

pair of hitmen

are assigned to

dispose of

Wilson. The

extreme colors

of the sources

found on

location formed

the basis for

the lighting,

and were then

amplified.

“For another scene in which Wilson takes a nighttime cab ride, we literally shot without even being able read my meter because there was so little light. Just before we started shooting, an inverter went out, so we lost the supplemental lighting we’d set up in the cab, but we just decided to go for it. I told Steven, ‘Either this will be a reshoot, or it’ll look great.’ And it did look great. Terence Stamp was in the back seat and I could just barely make out his shape through the viewfinder, but the footage turned out remarkably. I couldn’t believe how much information the stock held. Also, where you would normally lose your blacks, because the curve is going into underexposure, the Vision Premier really brought them back.

“In that cab scene, I pushed the 5289 by one stop, but the Vision Premier held the blacks,” Lachman adds. “I always underrate my stocks while shooting, though, which helped the grain.” The cinematographer estimates that he used the 89 on about 20 percent of the film, employing 5279 for interiors and EXR 5293 for daylight exteriors.

Addressing the lab work done on the picture, Lachman details, “Our lab was CFI, my lab of preference, and we worked with Art Tostado and Ron Scott over there. They have good, consistent dailies, and they aren’t afraid to reprint something if they feel it doesn’t look right. Because of the expense, some other labs won’t do that, and they’ll send something on even if one roll doesn’t match the previous one because the printer lights have somehow been changed. All of the labs are technically about equal, so what it comes down to is customer service.

“Unfortunately, on both The Limey and my previous picture, The Virgin Suicides, which was directed by Sofia Coppola, we only printed selected takes or rolls in order to save money. I can’t stress enough that I feel it’s a false ‘savings.’ Some people think its a luxury or reward for a cameraman to see dailies on film — and maybe there is a secondary sense of pleasure about it — but if you’re having any technical problems, you’re not going to see it in video dailies. I have yet to be on a film where a lens didn’t perform improperly at some point, or a light didn’t have an inadvertent change in color temperature that affected a shot. On The Limey, we caught a lens that went out on us. The act of moving around day in and day out can damage or affect the cameras and lenses, and those nuances can’t be seen on video dailies — the sharpness, contrast or even steadiness of the image. If you’re spending $2 million — or even $50 million — on a picture, you can’t find yourself in post-production with shots that are ruined by technical problems. It’s much more expensive to go back and reshoot rather than have projected dailies and make sure that any problems are corrected during principal photography. It’s a ludicrous attempt to save money, and I’ve talked to a number of cameramen who have had major photographic problems on their films but only found out about them after the fact. All cinematographers — and producers and directors — should address this issue. Everyone’s concerned about the need for film preservation, but let’s get things on film correctly first, and then preserve it.”

Lachman lit Valentine’s modernist mansion in the Hollywood Hills primarily with augmented sunlight, using 18K HMIs coming through the windows: “I mixed the temperatures in there, using straight tungstens on practical inside so they’d be warmer than the exterior windows. However, because the windows were so burned out, we almost completely lost their color.”

During a daytime party sequence staged there, Wilson and Ed loiter outside on a narrow platform jutting over the edge of the hillside, waiting for a chance to confront Valentine. In one panoramic shot, the pair look out over smog-choked Los Angeles, incredulous that anyone would pay for such a view. “That’s Steven’s favorite shot,” Lachman says. “Here’s someone who has built a multimillion-dollar house to see just... whiteness. You know L.A. is out there somewhere, but there’s nothing to see.

“One problem with filming up in the hills is logistical: how do you get the crew and equipment up there and parked? While shooting in the house, there was no place to put the equipment, because we were filming so much of the area. Of course, you also have to deal with the neighborhood. I find it ironic that Hollywood is one of the worst places in the world to shoot a movie on location - nobody wants to be next door to a production, because I guess that’s what they do at work all day.

“That said, our location house had all of these great windows that were terrific sources for light, allowing us to basically work off what was there. The interior was also primarily white, so that helped us as well.”

At Valentine’s mansion in Big Sur, Soderbergh wanted to stage a climactic chase scene between Wilson and Valentine on the shore below some steep cliffs, an area that was basically inaccessible for standard filmmaking gear. “The solution was to build a cable system in order to fly some HMI lighting balloons over the area, so we could view the sea, the cliffs and this house,” Lachman details, noting that he’d never used such floating fixtures before. “It was a real process. The major problem was getting these cement stanchions out into the sea, and then rigging the cables to hold the balloons in place. We didn’t know how viable our plan would be because the winds were unpredictable, but we were lucky over the two nights we shot down there.

“Another problem was the tide changes, because we just had this very narrow rocky shoreline, which almost completely disappeared at high tide. After a few takes in any given position, we’d have to move everything because the waterline was changing. The balloons helped us in this regard, because they carried such a broad area that we never had to move them around.

After this experience, I’m a big fan of using balloons, but there’s still something to be said about using Condors. If you want a general light over open space, balloons are great, but [the light] has no direction to it.”

Working with production designer Gary Frutkoff, Lachman regularly tried to incorporate lighting into their settings. “At the Big Sur house, we used Malibu lights around the grounds leading into the darkness, and practical on the house itself,” the cameraman offers. “Steven wanted a very stark, cold nighttime world outside, which was provided by our HMI balloons. The house interior is very warm, in part because you see so much wood — beautiful teak and cedar — and it was predominately lit by a fireplace for most scenes.” The fireplace was already rigged for gas, and the illumination was boosted with the used of small lamps on flicker generators.

Considering the artfully down-and-dirty style he used to shoot The Limey, Lachman offers, “It’s interesting to watch the trends in cinematography, and it seems that the pendulum has been swinging away from the direction of creating cosmetically ‘perfect’ images. Film stocks are so grainless and wonderful, and lenses are so pristine and sharp, that I feel we need to go back a bit in the direction of feeling that something is ‘real,’ so that we’re not manufacturing some homogenized abstraction of reality.

“Steven understood that if we were going to approach the storytelling, these were the kinds of images we’d find. It excited him to explore different ways of telling the story of The Limey photographically. If you’re going to investigate this low-rent, underbelly world, why not use a low-rent means to tell the story? I think audiences want stories about real human emotion and conflict, and moving away from sterile technical perfection can help on those kinds of films.”

Lachman went on to earn Academy Award nominations for his films Far From Heaven (2003) and Carol (2016) was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017.

For access to all 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.