Lords of Illusion: The Prestige

Shot by Wally Pfister, ASC and directed by Christopher Nolan, this period drama tells a compelling tale of rival magicians.

Unit photography by François Duhamel, SMPSP and Stephen Vaughan, SMPSP

Cinematographers often invoke the art of smoke and mirrors, sometimes in a very literal sense, in their visual storytelling. The very science of motion pictures is a kind of cinematic legerdemain, with the director of photography serving as the magician who guides the audience’s eye to a precise area of the frame through the delicate balance of color, light and shadow.

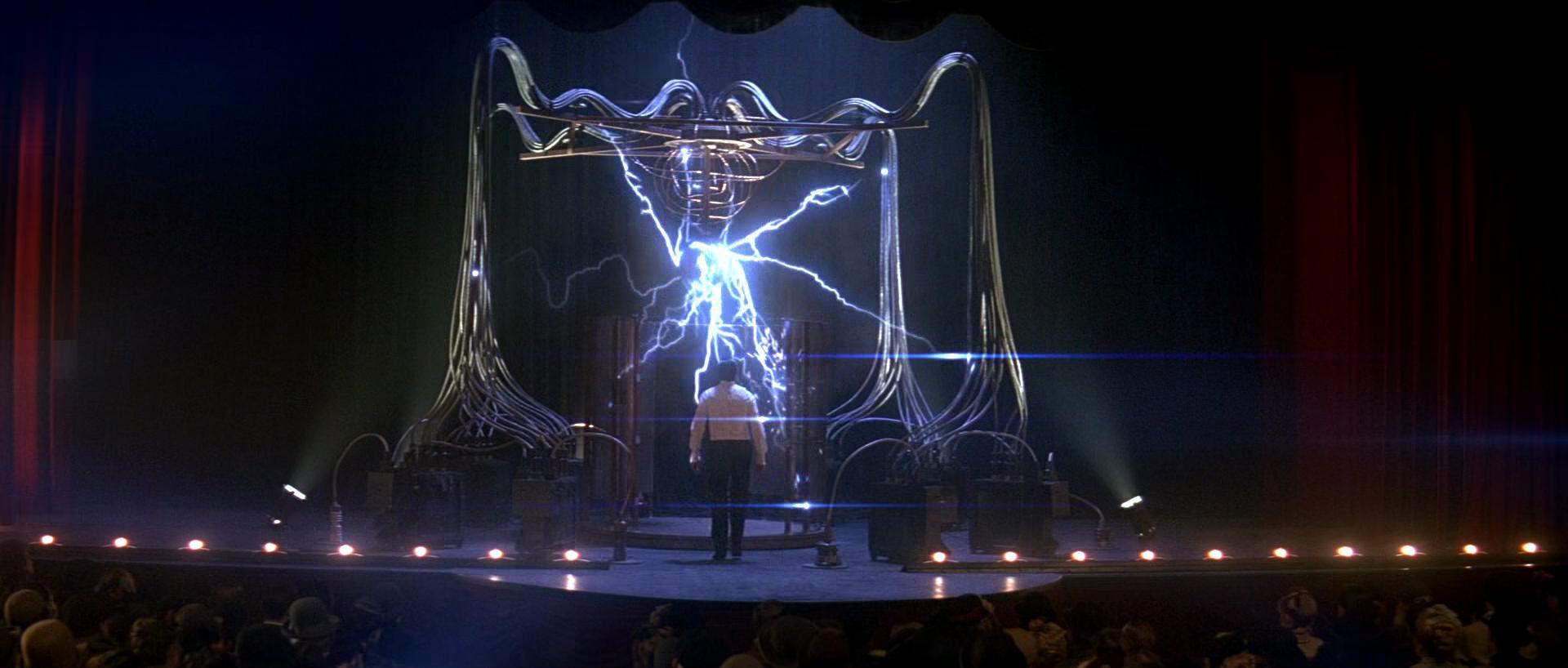

Academy and ASC Award nominee Wally Pfister, ASC has been practicing this photographic prestidigitation for more than 20 years. The title of his latest project, The Prestige, refers to the third and final act of an illusionist’s magic trick when the amazing and impossible is accomplished before the audience’s eyes. Based on the 1995 novel of the same name by Christopher Priest, the film centers on the friendly rivalry between two competing magicians, American Rupert Angier (Hugh Jackman) and Englishman Alfred Borden (Christian Bale). Borden seems so adept at accomplishing the impossible that Angier begins to suspect his rival isn’t using sleight of hand at all, but has somehow harnessed the power of real magic. Naturally, Angier will stop at nothing to discover Borden’s secret.

The Prestige reunited Pfister with director Christopher Nolan, for whom he shot Memento (see AC April ’01), Insomnia (May ’02) and Batman Begins (AC June ’05). Prior to embarking on their latest venture, Nolan told Pfister he wanted to shoot “down and dirty,” simplifying the physical requirements of the filmmaking process. “When Chris came to me with this project, he was really itching to do something much more grounded, much simpler in terms of our approach,” says Pfister. “Batman Begins required a very complicated strategy to deal with the visual effects, practical effects, and grand scope. For The Prestige, Chris wanted to take an approach that involved less waiting-around time. He likes to go, go, go, and he asked me if we could work in a more organic style and move really fast. Right off the bat, we talked about how much lighting we would need to do. Could we take a Barry Lyndon-like approach and light practically with real candles? Nothing would make Chris happier than if we could light a scene with only candles, so I started down that path to see what was possible.”

Pfister began experimenting to see how far he could push modern film stocks. One weekend, he borrowed a camera from Panavision and took it to Nolan’s house. “We had some dinner, and then Chris, Emma [Thomas, Nolan’s wife, and the film’s co-producer] and I shot some footage in nothing but candlelight. I brought some [Kodak Vision2 500T] 5218 and broke off a number of rolls, designating them for 1-stop, 2-stop and 3-stop force-processing. Three stops was kind of crazy, but Chris and I wanted to see just where the film would go and how much it would fall apart. Well, it fell apart completely — at 3 stops it was just a mess. Even at 2 stops, the stock was really quite milky, but, surprisingly, we did get an image. Later on, as we continued testing, I rejected the possibility of pushing 2 stops because the result was too milky and grainy for me. Fortunately, I was able to talk Chris out of gaining light that way. I explained to him that it would be more difficult to clean up later on, and it wouldn’t save us any money.”

“They weren’t movies we were trying to copy or emulate, per se; the ones we chose were just successful visual movies. Barry Lyndon was probably the closest, visually, to our concept. It was an interesting education.”

—Wally Pfister, ASC

Pfister and Nolan also put together a list of films to screen at Warner Bros. each week during prep. Along with producers Thomas and Aaron Ryder, production designer Nathan Crowley, and “anyone else who wanted to join, we had these movie parties and said, ‘Let’s watch this, it might apply,’” Pfister recalls. “They weren’t movies we were trying to copy or emulate, per se; the ones we chose were just successful visual movies. Barry Lyndon [AC March ’76] was probably the closest, visually, to our concept. It was an interesting education.”

After his research and testing, Pfister settled on shooting most of the film on 5218, and some scenes on Vision2 250D 5205. “I’ve used 5205 a lot on commercials, and it tends to be a little too low-contrast for me, so I push it a stop and rate it at 400 ISO. I also pushed the 5218 a stop for a lot of the film, rating it at 800 ISO. I found that 5218 pushed one stop is really good in terms of grain; the 18 adds color and contrast where I like it, but it does tend to block up in the mid-range quite a bit. I tried not to push it as often as we could get away with it, especially if we were shooting at one of the stages where the magicians perform, because I knew we’d have to light there. Why push when we have to light already? I saved the pushing for when we were shooting almost entirely with practicals when we really needed the extra stop.”

In addition to squeezing sensitivity out of the emulsion, Pfister turned to Panavision senior technical adviser Dan Sasaki to procure a set of prototype high-speed anamorphic lenses that open up to T1.4. “There are two ways to get more light: one is through lab manipulation, and the other is by getting faster lenses,” explains Pfister. “Chris and I have done all of our films together in the anamorphic format. We wanted to stick with that approach, but I was concerned about the speed of the anamorphic lenses in relation to the minimal lighting style we were planning to use. I put the challenge to Dan, he applied himself to the task, and after a couple of months of R&D, he came back to us with some spectacular lenses. He made us 35mm, 40mm, 50mm and 85mm anamorphic lenses that could open up to almost T1.3. They fell apart a bit at that stop, but they looked absolutely beautiful at T2. I was able to shoot quite a bit of the film at T2 or T2.4, which was really amazing.”

Sasaki explains, “It’s difficult to work with such a large surface area of the glass and still get great results. A lot of the aberrations that are easily correctable at T2.8 double themselves at T1.4, and it took a lot of massaging to create an image at that stop that we could call ‘Panavision.’ The new high-speed anamorphics are a lot like the E-Series lenses, in that they have a very organic feel. To save some time, we used old E-Series housings and put new glass in them. They look a little chopped up and glued back together, but we got some fantastic results. The prime elements are high-speed Zeiss glass with proprietary Panavision anamorphic cylinders.”

Pfister doesn’t mind mixing his lenses. As he did on Batman Begins, he used a combination of C- and E-Series anamorphics for The Prestige. “I’m not overly technical about my lens selection,” he confesses. “I want them to have good contrast and match color fairly well, but beyond that, I really look for what feels best to me. My 1st AC, Bob Hall, is extremely good at testing and putting together a good set of lenses for me, and I trust him to take care of that. What was really amazing about having these new lenses made, and being part of the process, was that I got to tweak them a bit to suit my taste. Dan would show us flare tests and talk about how we could tweak the individual flare properties of each lens. With a few adjustments, he could make the flare bigger, smaller, harder or softer. It was amazing to have that option presented. In the end, Dan created an astounding set of lenses that are just gorgeous. I think they just may be the most beautiful lenses I’ve ever put light through, especially at a T2, which I haven’t done in years. I’m also very thankful to have an extraordinary 1st AC like Bob, who can pull off the focus at that stop!”

The filmmakers strove to find practical locations in and around Los Angeles that could be redressed as turn-of-the-century London. Pfister explains, “Chris and I had both just had kids — our third each — and we all really preferred to stay close to home for this film. Even though the story takes place in London, [production designer] Nathan [Crowley] was confident we could utilize L.A. for London and stay in town without having to build too much on stages.” The trio scouted the streets and alleyways of downtown Los Angeles, paying particular attention to the area’s historic proscenium theaters.

“A lot of the architecture in downtown L.A. is actually very similar to what you might find in 1906 London: big brick buildings, alleyways, and so forth,” says Pfister. “Chris didn’t want the movie’s period to get in the way of the storytelling, so we decided to break with convention by using a handheld camera throughout the film, which is not often done in movies depicting the turn of the century! That was a lot of fun, because it was a different approach to this type of material.”

Knowing that the project would involve significant handheld work, Pfister chose the Panaflex Millennium XL2 as his main camera. “I made the decision to operate myself, primarily because of the shooting style we had in mind. Not only were we trying to keep the lighting simple, but Chris also wanted to give the actors total freedom of movement. That meant the camera was on my shoulder the whole picture, which allowed us to handle the entire execution in a very organic way: the actors were free to move around however they wanted, and I followed. We were often showing 180 to 360 degrees in each location. In certain scenes, Chris empowered me to make decisions about where the camera would be at any given moment. It was a very documentary-like style, and I was helped considerably by the years I’d spent shooting docs and working in cutting rooms. Chris never told me who to follow or where to point the camera. Instead, he told me, ‘Go with your gut. If we’re missing pieces, we’ll pick them up in the end.’ That’s exactly how we did it, and I think that gives the film a very free spirit.

mechanical effects play a large role in the film, which is set in London during the early 1900s.

“That kind of shooting can work with an operator, but there can also be a detachment when you bring in a third party,” he continues. “Chris trusts me enough to let me tell the story with the camera. He also prefers simplicity, and having a third person in this kind of relationship requires more communication and time. Chris isn’t a director who sits back in video village; he’s right beside the camera, which creates a certain intimacy between us and the actors 12 feet away.”

Pfister is quick to point out that this working style is not for every production. “I couldn’t have done The Italian Job without an operator as good as Scott Sakamoto. I don’t feel like I always have to operate, and I value the input from a great operator. But in this case, it worked much better that I was the one with the camera on my shoulder. However, we did carry a standby operator, Craig Fikse, who did most of the Steadicam work.”

“I know there are a lot of directors who love shooting with two cameras to maximize the coverage quickly. If you do that, though, you always have to compromise something, and it’s not always the lighting.”

The cinematographer admits that from a physical standpoint, handholding the camera for nearly the entire show was an exhausting challenge.“In the beginning, I really started to fall apart physically; it was like training for a marathon. After about five grueling weeks, I was finally able to keep up with the pace after sufficiently developing the muscles in my shoulders, upper and lower back. When I really got in trouble, we tried using an Aaton camera, but the anamorphic lenses made it too front-heavy, which created a whole new set of problems. In the end, the Millennium XL2 was the best option; I just had to train on the job to keep up with the demanding handheld work Chris was throwing at me.”

The handheld style permeates the whole film and was even used for establishing shots that would typically be captured with cranes or dollies. Nolan and Pfister took a different approach to these wide masters, keeping them more reserved and not dwelling on the grandeur of the period elements. The cinematographer observes, “You always see period films with big, sweeping shots of London streets that show horse-drawn carriages and people wandering about in period clothes. Those pictures try to sell the idea of the period with big production shots, but we decided to go against the grain; our establishing wide shots are more like a brief peek around a corner. The perspectives are tighter and more voyeuristic.”

This approach also dictated that the majority of the film would be shot with a single camera. On the topic of single-camera shooting, Pfister offers,“I know there are a lot of directors who love shooting with two cameras to maximize the coverage quickly. If you do that, though, you always have to compromise something, and it’s not always the lighting. When you’re shooting with two cameras, the actors’ eyelines inevitably suffer. No matter how close you get the cameras together one camera is always going to be further off the ideal eyeline at any given moment. Chris and I also agree that unless you’re doing a movie like Mike Figgis’ Time Code [AC April ’00], where simultaneous images are used as a creative tool, only one image is going to be on the screen at any given time, so only one camera is needed to capture it.”

An added benefit of the organic, handheld style is that coverage can happen very quickly, often within a single shot. As a result, the crew on The Prestige enjoyed 10-hour workdays and finished the film three days ahead of the original 60-day schedule, according to Pfister.

Given his combination of high-speed anamorphic lenses and fast film stock, Pfister found that he was lighting less and less over the course of the shoot. “In the end, we only did a couple scenes just with candles. Most of the time, I was augmenting a bit, but honestly, it was very little. I found these LitePanels LED fixtures in an ad in American Cinematographer featuring my friend Mauro Fiore [ASC], and those things were great for adding a subtle boost to our candlelight. They were really fantastic.”

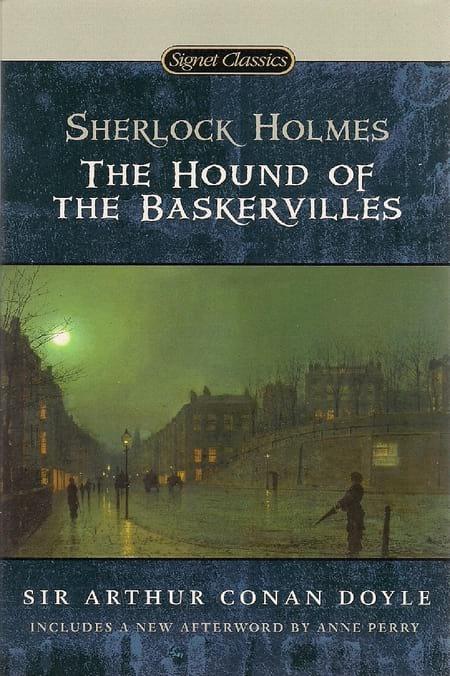

Inspiration for the film’s lighting style came from an unexpected source. “I was saying goodnight to my son one evening, and on his desk there was a copy of The Hound of the Baskervilles, which he was reading for school,” recalls the cameraman. “I looked down at the cover and thought, ‘That’s it, exactly! That’s the look I want for the night exteriors of the London streets!’”

The book sitting on his son’s desk was a Signet Classic 100th anniversary paperback edition of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s beloved Sherlock Holmes tale. Its cover features a painting of turn-of-the-century London by John Atkinson Grimshaw, entitled “View of Heath Street by Night.” Pfister enthuses, “I loved the soft contrast of it — a little warmth from the glow of the gaslight, but also this great green cast. It was exactly what I had in mind. I also found another painting by Grimshaw called ‘Boar Lane,’ which was a great inspiration.”

A prime example of Pfister’s low-tech approach is a sequence shot at a Victorian-era museum in Pasadena that doubled for Borden’s home. Because the museum already offered perfect set dressing and ambiance, very little additional work was required to prep the location. Pfister kept things even simpler by lighting with the museum’s existing fixtures. “The scene involved an argument between Borden and his wife [played by Rebecca Hall],” he explains. “We were using the museum as their living room, and during the location scout, I had noticed this beautiful chandelier. While we were walking through, I stuck my meter out and found that the chandelier was giving me a reading of T2.8. That was even more light than I needed, so I could afford to diffuse it. On the actual shooting day, we came in and shot the wide stuff with the natural chandelier. When we went in tighter, I simply wrapped the fixture in a layer of 251 diffusion, and it created a beautiful half-key light on the actors’ faces. I wound up shooting that scene at T2.3, and it looked fantastic.

“That scene was shot with almost no movie lights at all,” he continues. “There were these great sconce fixtures on the walls in the background that added some wonderful texture, but that was it. I could have put up a movie light to mimic the chandelier and get a little more stop, but then I would have had to augment the sconces and add more light to the background. When you start doing that, it suddenly becomes an arms race. Why do it if you don’t have to?

“Of course, in a situation like that, the light doesn’t look great from all angles. Only certain angles are going to look good, so you have to assert more control over where you’re shooting. For that scene, we gave the actors marks, and I only shot from one side. The key is knowing what looks good. That kind of lighting — or not lighting — can easily look like crap without the proper approach. It may sound a bit immodest to say that, but it’s the truth. Quite honestly, I rely on every ounce of my experience to take this kind of approach to a big feature and still have it look right. I used these kinds of low-tech techniques when I was starting out with Roger Corman, but it’s the years of experience since then that have given me the confidence to return to those techniques and carry them off with more quality and style. I feel I’ve reached a point in my career where I can take a major risk and still have the confidence to do a good job. That said, I don’t want to give the impression that we didn’t use any lighting on this film, or that you don’t need to light in general. The scene at the museum was a special circumstance where we could be much more clever and organic with our lighting, so we took a very minimalistic approach.”

Warming to this subject, Pfister says that his approach to cinematography is greatly influenced by the work of Gordon Willis, ASC. “Willis was never afraid not to use a light. He was never afraid to use practical lights or whatever it took to bring the story to life. Honestly, he’s my absolute hero. Every time I do something, his work is in the back of my mind. Watching his films taught me that cinematographers can serve as partners in the storytelling, but that we should never grandstand or force anything that will work against the story we’re trying to tell.

Providing another example of his stripped-down approach to The Prestige, Pfister cites a scene set in the workshop of Cutter (Michael Caine), who serves as Angier’s ingenieur, the craftsman who creates the technology behind the magic. Cutter’s shop is a large, loft-like space with a big picture window. Pfister decided to work the short scene — a dialogue between the two characters — entirely in natural daylight with no additional augmentation.

“Our working style on this film was an incredibly liberating experience for me. I really enjoyed not being fussy with the lighting, letting things go raw at times, and sometimes not lighting at all.”

For scenes where lighting was required, Pfister allowed the film’s era to dictate his choices. In London in 1905, electrical power was just beginning to replace gas- and firelight, so the cinematographer could pick and choose from these three sources, depending on the environments of various scenes. While shooting on the upscale theatrical stages where the magicians perform, he turned to electric light fixtures. Source Four ERS fixtures with 2K backs simulated “limelight” theatrical spotlights, while tungsten balloons provided a soft, overall ambiance. Scenes involving gaslight fixtures were illuminated with a combination of actual firelight and electrical fixtures, simple gas lamps with glass chimneys. To simulate the effect of handheld lanterns, Pfister and gaffer Cory Geryak rigged up some “super lanterns” for the actors to work with, incorporating 750- watt tungsten globes that were powered through AC cables hidden in the actors’ clothes.

Another fixture that was created specifically for the film was the “EB” or “Easy-Bake” light, named for the intense heat it generated. Geryak strung 1K globes together in groups of three or five, mounting them in softbox housings created with pieces of material from firemen’s turnout coats that had been riveted together. The faces of these fixtures were covered with the diffusion of choice, and the small units could be placed in corners or easily hidden. “The EB fixtures created a great throw that would reach all the way across a room and give me a decent stop,” says Pfister.“I was usually using Light Grid on them. They ranged in size from 1-by-2 feet to 5 feet long in a big, soft snoot. I must share credit with my exceptional key grip, Ray Garcia, who always had his eyes and ears sharply focused on the set, and whose contribution to the film is evident.”

Addressing the film’s post phase, Pfister notes that “the prints were skillfully timed, in a completely photochemical process, by David Orr at Technicolor in North Hollywood, and the results reflect exactly what we had been hoping to achieve way back in our earliest conversations about how to tell this story.”

Reflecting upon his overall experience with The Prestige, Pfister enthuses, “Our working style on this film was an incredibly liberating experience for me. I really enjoyed not being fussy with the lighting, letting things go raw at times, and sometimes not lighting at all. I could really feel the shackles being unlocked. It was an exciting approach and a great way to work. I’m very grateful that Chris took me to that place, and I’m extremely proud of the results.

TECHNICAL SPECS

Anamorphic 2.40:1

Panaflex Millennium XL2

C- and E-Series lenses

Kodak Vision2 500T 5218,250D 5205

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.