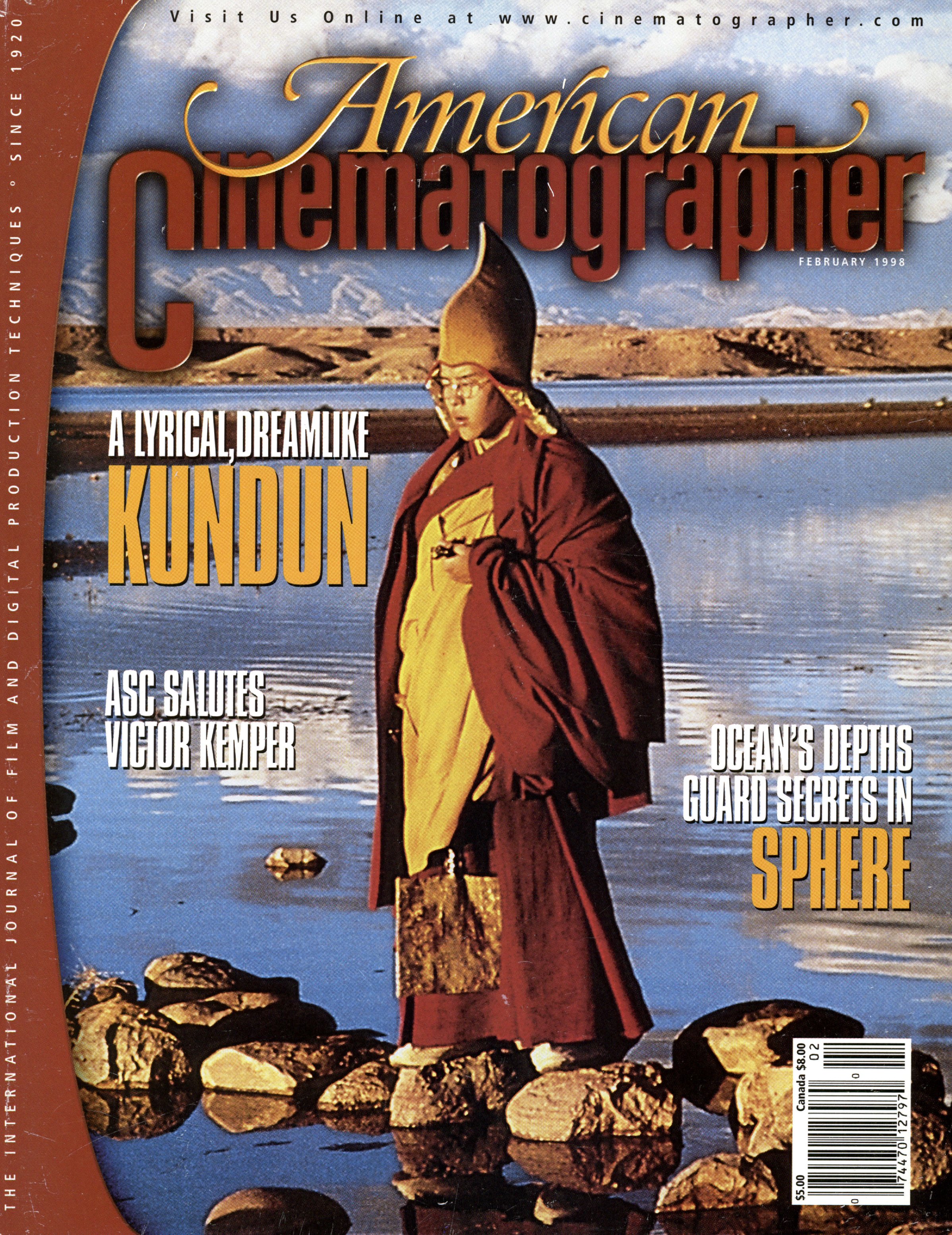

Kundun: Raising Tibet in the Desert

Cinematographer Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC, production/costume designer Dante Ferretti and a multinational crew go on location in Morocco to capture a spiritual essence.

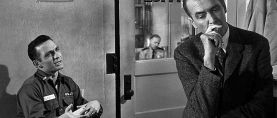

Unit photography by Mario Tursi, courtesy of Touchstone Pictures

The year is 1959; high up in the frigid reaches of the Himalayan mountains, a bone-weary traveler on horseback slowly approaches an Indian border crossing, surrounded by a small phalanx of fellow riders. As he dismounts, this forlorn figure is stopped by sentries, who quickly realize the significance of the moment: the man standing before them is none other than the Dalai Lama. Expelled from his Tibetan homeland by Chinese invaders, the deposed deity has nowhere else to turn for sanctuary.

Today, 39 years after his ouster, the Dalai Lama has yet to return to Tibet, which remains a near-mythical realm in the minds of most Westerners. Situated on a high plateau in southwest China, at an average altitude of 16,000 feet, this storied land is known as the cradle of Buddhism, a religion with millions of followers the world over. Since it was forcibly assimilated by the Chinese (who promptly rechristened it Xizang), Tibet has been shrouded in the melancholy aura of a lost civilization. Due to the persistent efforts of its spiritual leader, however, the region has remained alive in the public consciousness as the focus of an enduring political controversy. Thus far, the Chinese government has scorned the Dalai Lama’s attempts to rally worldwide support and restore Tibet’s independence.

Martin Scorsese’s latest film, Kundun (a term meaning “Ocean of Wisdom”), traces the life of the Dalai Lama from infancy to adulthood. The tale begins in 1937 at a small farmhouse in rural Tibet, where precocious, two-year-old Tenzin Gyatso has enjoyed an idyllic childhood with his loving family. The clan’s peaceful existence is forever changed, however, when a group of Tibetan scholars arrive at their door. Intent on locating the 14th reincarnation of the Buddha, the scholars soon determine, through a series of tests, that Tenzin is the new Dalai Lama. The boy and his dumbfounded family are immediately escorted to Lhasa, where little Tenzin is enthroned as the country’s spiritual leader.

“Marty had the script very clearly in his mind, and he had a very definite concept about how he wanted the film to feel.”

— Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC

While adjusting to his new life, Tenzin is tutored by the best Tibetan scholars; in 1950, during his 15th year, these teachings are put to the test when the Chinese communist army of Chairman Mao Zedong invades the country, claiming it as part of China. The Dalai Lama’s attempts to resolve the situation through nonviolent diplomacy fail, and he is forced into exile nine years later, at the youthful age of 24.

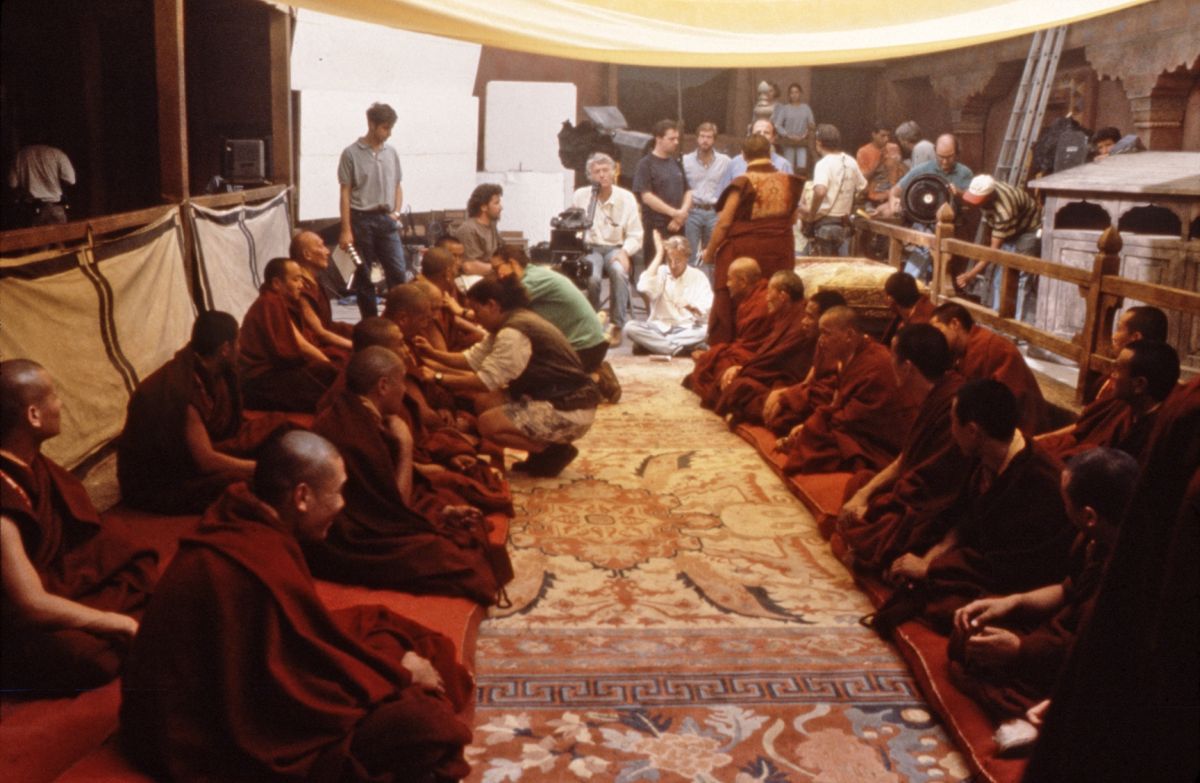

In bringing this story of personal struggle to life, Scorsese and his crew faced an array of artistic, technical and logistical difficulties. Determined to lend their intimate film an emotional resonance, the director and producer Barbara De Fina cast the film with native Tibetans, none of whom were professional actors. The part of the Dalai Lama was played by four different boys (aged 2, 5, 12 and 18), and other key roles were assigned to actual members of the Tibetan leader’s family. In fact, the Dalai Lama himself served as a consultant on the project, working closely with screenwriter Melissa Mathison and the filmmakers.

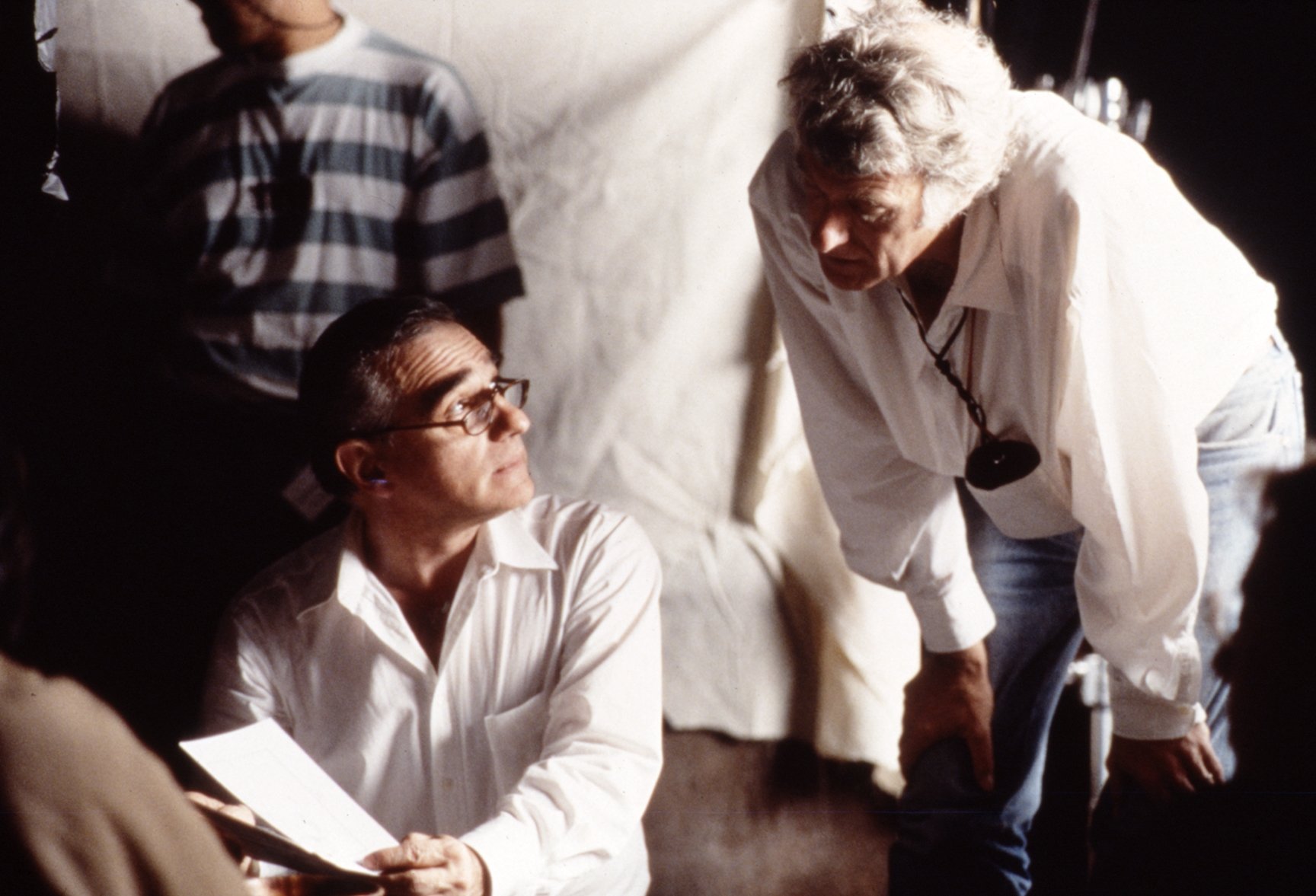

Scorsese’s insistence upon picturesque locations presented further challenges. Denied permission to shoot in India, the production headed for Ouarzazate, Morocco. Over the years, this small municipality has developed into a staging post for tourists headed into the Sahara Desert; it also offers a motion picture facility, the Atlas Film Studio, located just 15 minutes from the center of town. But as director of photography Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC notes, the working conditions in Morocco were a far cry from the luxuries of a Hollywood studio. “I went to Morocco for about 10 days with Marty sometime in June of 1996,” recalls Deakins. “It was a bit of a scramble to find the locations we needed. We saw some locations we knew we weren’t going to use, and we also saw the Atlas Film Studio, which was built years ago when a James Bond picture shot there. The studio ‘entrance’ consisted of a mud wall with this door in the middle, and when you went through, there was one small ‘stage’ really just a warehouse surrounded by an expanse of desert. It was really surreal.”

The rough working conditions did little to deter Deakins, who has earned the admiration of both critics and his peers with outstanding work on such features as The Shawshank Redemption (which earned him both an ASC Award and an Academy Award nomination; see AC June 1995), 1984, Courage Under Fire and Dead Man Walking. The cinematographer is probably best known for his collaborations with the Coen brothers: the ASC- and Academy-nominated Fargo (AC Mar. ‘96), as well as The Hudsucker Proxy (AC April ‘94), Barton Fink and the upcoming feature The Big Lebowski. However, it was his impressive photography on the scenic dramas Pascali’s Island and Mountains of the Moon which actually caught the director’s eye.

“Given the practical realities of a set or location, we couldn’t achieve the precise shots that Marty wanted; if I saw that something wasn’t going to happen the way we’d planned it, I’d talk to Marty and we’d come up with an alternative.”

To ease his burden a bit on Kundun, Deakins brought some of his key crew members from the United States: gaffer Billy O’Leary, dolly grip Bruce Hamme and camera assistant Andy Harris. “The key grip, Tommaso Mele, came from Italy, and he was wonderful,” Deakins enthuses. “The rest of the grip crew was also Italian, as were the balance of the electricians. They were all really helpful. We also had a great English operator named Peter Cavaciuti, who handled the B-camera and Steadicam work.”

The cinematographer says that careful planning and his detailed discussions with Scorsese helped prepare him for the arduous nature of the show. “Marty had the script very clearly in his mind, and he had a very definite concept about how he wanted the film to feel. Even before going to the location during prep, he had broken down each scene into a specific style. If he wanted a particular scene to be a long, moving camera shot on dialogue, he would have that down, maybe along with a couple of close-ups he wanted to use to heighten specific parts of the sequence. On another scene, he might have things broken down into a much more conventional series of close-ups on dialogue. He did this even before locking down the locations or actually seeing the final sets!

“Those sketches were what we primarily worked from,” he continues. “The day before we shot a scene, we might have a brief conversation about the next day’s work, but we basically worked from his initial conception. Of course, sometimes, given the practical realities of a set or location, we couldn’t achieve the precise shots that Marty wanted; if I saw that something wasn’t going to happen the way we’d planned it, I’d talk to Marty and we’d come up with an alternative.

“I don’t know if that’s the way he’s worked before, but for me it was great,” he maintains. “Generally, I was surprised at how often I was left to my own devices in terms of lighting the shots and choosing a lens. After seeing the sets and locations, I would take Marty’s script notes and transform them into little diagrams showing where the camera would be for each shot, which order to shoot things in, and so on. Overall, I felt as if I had a lot of input; Marty gave me quite a bit of his trust, and I did the best I could to get what he really wanted.”

The cinematographer says that his earliest strategy sessions with Scorsese revolved around their use of the Super 35 format for widescreen compositions. “I shot Air America in Super 35, so I was familiar with it,” he notes. “I feel that there are good and bad aspects to the format. Technically, it’s pretty good these days, though there is a definite loss of color intensity because the whole Super 35 process involves an optical. On balance, though, I think Super 35 was the best way to go on this film; the slightly less saturated colors actually add to the naturalism we sought. Most of the interiors take place at night, and our only practical sources in those scenes were butter lamps little wicks in bowls of butter fat. In general, I like to make a light source look as if it’s really working, instead of overpowering it with an artificial source. I do use gag lights, but I like the sources themselves to be very bright within the scene. In this particular respect, the Super 35 format has the advantage over anamorphic, because it allows you to use faster spherical lenses.”

“I like using prime lenses because it forces you to move the camera and think about where the camera needs to be.”

Deakins opted to shoot most of Kundun with Zeiss Superspeed and standard-speed lenses. For closer shots, his favored lenses were the 40mm and 50mm in keeping with the cinematographer’s oft-stated preference for focal lengths which simulate a human eye’s actual field of view. “A lot of times, though, I put on a wider lens than Marty had imagined,” he admits. “We were occasionally shooting with a 14mm to see the scale of some of our sets often because we couldn’t float the walls. Even if we could, the ‘stage’ wall might only be a few feet behind the set wall.”

The production did carry a Cooke 18-100mm zoom lens, but it was used sparingly. “I like using prime lenses because it forces you to move the camera and think about where the camera needs to be,” he maintains. “That’s the way Joel and Ethan Coen work, and Marty is very much the same way. We really only needed the zoom for this one specific shot that we did, which occurs within a dream sequence that we’d talked about well in advance of the shoot. The camera starts in really close on the Dalai Lama’s eyes, and then pulls back and tilts down to reveal him standing amid this array of dead monks in red robes.

“The camera then begins rising straight up until he’s back in frame at full figure, surrounded by this sea of bodies. There was no way of tracking with the 75’ Akela crane we used, so in order to get the size we wanted on the Dalai Lama’s face at the beginning, and still have a move with a fluid feeling, we used the zoom to widen out at the end of the move. As the camera neared 50’ and rising, the perspective shift on the wide end of the lens became very slight; this allowed the effects people at Dream Quest Images to continue the move even further while adding extra bodies to fill the outer edges of the frame.”

Hewing to his desire to let real sources do as much work as possible, Deakins shot most of the film at an aperture of T2.2 or 2.5. “If you shoot at 5.6, the candles aren’t going to do anything,” he says. “We had some big night exteriors where I would have dearly loved a deeper stop, but using all of the HMI lights at my disposal, I could only manage a stop of 2.4 and still keep a thick negative. I always try for a thick negative because I don’t like to lose richness in the blacks. I always overexpose a little, and I’m usually printing in the mid-40s.

“During day interiors, I was probably lighting to a 2.8 or even 3.2, and when high-speed work was involved in a scene, I would light the whole scene higher in order to make the matching easier. On exteriors, it really depended upon the kind of depth of field we wanted. In those types of situations, I like to have good depth, because to me that seems to be the more natural way of seeing things. I tended to use a .3 neutral-density filter and shoot at about 8 or 11 for bright exteriors.”

The cinematographer exploited Eastman Kodak’s Vision 500T 5279 stock for all of his interior and exterior night work; he switched to EXR 5293 for day interiors or dusky exteriors, and EXR 5248 for day exteriors. “The 79 is terrific, because it’s so fast; it really is 500 ASA. I began rating the 79 at 400, but I found I could really rate it at 500 and not worry about losing the blacks.”

Deakins notes that Kundun relies heavily upon its atmospheric staging and locations. “I think this film is very much a poem rather than a traditional narrative film,” he opines. “It’s more of a mood piece involving a specific time and place in history, so our main challenge was to capture that. Morocco is not at the same altitude as the spot we’d initially chosen in northern India, and the mountains aren’t quite as present; it’s also much more arid, which was kind of nice. The Tibetans were constantly saying how much it reminded them of their homeland, and they got a bit tearful at times, which was a pretty good gauge of our location’s appropriateness.”

Of course, Deakins wasn’t alone in his quest to transform Morocco into Tibet; also joining the caravan was expert production designer Dante Ferretti, who did double duty as the film’s costume designer. Over the course of his long and illustrious career, Ferretti has earned four Academy Award nominations (Interview With the Vampire, Hamlet, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen and Scorsese’s The Age of Innocence). His impressive list of credits also includes another successful collaboration with Scorsese (Casino), as well as five films with Federico Fellini (The Voice of the Moon, Ginger and Fred, And the Ship Sails On, City of Women and Prova d’Orchestra) and a half-dozen pictures with Pier Paolo Pasolini (120 Days of Sodom, Arabian Nights, The Canterbury Tales, Oedipus Rex, Decameron and Medea).

Once the production had selected the town of Ouarzazate as its primary location, Ferretti supervised the construction of a second, larger soundstage at the Atlas Film Studio. “It was really just another warehouse,” the production designer admits, “but we did all of our interiors there: the Potala Palace, where the Dalai Lama spent his winters; Norbulingka Palace, also known as the ‘summer palace’; Dungkhar Monastery, the Throne Room, and so on. The stage we built was 300’ by 200’, and about 50’ high. We also built a passageway to connect it to the smaller existing ‘stage’.”

Ferretti and his multinational team (“We had Italians, Moroccans, English and Americans in key crew positions”) redressed an existing street to resemble the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, using the concrete shells of unfinished houses as facades for their exteriors. The production also hired hundreds of Moroccans to help fashion the entrance to Norbulingka Palace and its walled gardens, which were built on the shore of a large reservoir located 40 minutes from Ouarzazate. Later scenes set within Mao Zedong’s Peking headquarters were shot at an existing building in Casablanca, while a field study center in the High Atlas Mountains, some 90 minutes from Marrakech, was converted into the exterior of the Dungkhar Monastery.

Ferretti concedes that his budget was not lavish; accordingly, he spent funds judiciously while still striving for sumptuous sets and costumes. “I did have a very low budget, but Morocco is not a very expensive place,” says the designer, who first worked there 30 years ago on Pasolini’s Oedipus Rex. “This is the kind of movie where the audience has to believe that they are actually in Tibet, so we built everything to be as real as possible. We used real flagstones for the floors of the sets, and I went to a factory in India to get the types of brocade, silk and fabric normally bought by Tibetan people. To do the construction, we hired a lot of Moroccan carpenters, plasterers and sculptors who did everything the old-fashioned way. Sometimes we had as many as 300 people working at once, but we could afford it because their fees were very low. There would have been no way to do it otherwise, because we had to build the big sets in about 14 weeks.”

“I didn’t want to make any compromises, and Roger did a good job of shooting and setting up his lights so that we could keep everything authentic.”

— production designer Dante Ferretti

“Absolute authenticity” was Ferretti’s ultimate goal. “I read a lot of books in preparation, and I had very good technical advisors. Namgyal Takla, the widow of the Dalai Lama’s brother, helped with the costume research, and I even had some meetings with the Dalai Lama himself; he did some sketches and floor plans for me. I didn’t want to make any compromises, and Roger did a good job of shooting and setting up his lights so that we could keep everything authentic.”

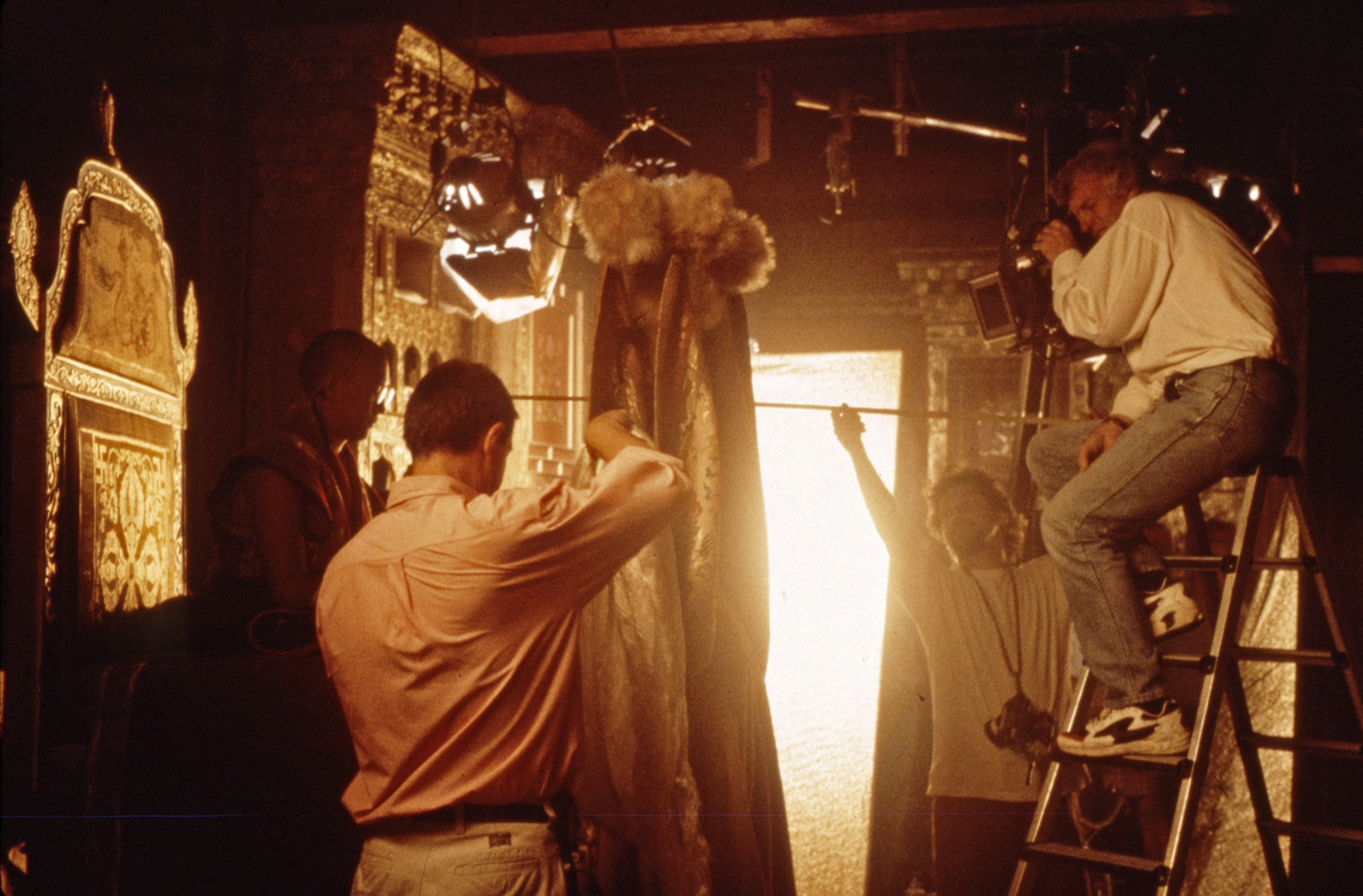

Deakins admits that the meticulous accuracy of Ferretti’s approach came with a price. “Because of the relatively low budget, it was difficult to have optimal setups,” he says. “With the sets built in warehouses that passed for stages, there were no rigs, no gantries, and no greenbeds up in the ceiling. The roof just wouldn’t support any real weight. I have to say, those sets were the most difficult I’ve ever dealt with, because of the situation we created. Dante really didn’t have the money to construct the sets the way I needed to build roofs that I could work on, platforms I could light from, or structures to which I could rig lighting fixtures. The sets were built as inexpensively as they could be and still look good, but they weren’t specifically structured to accommodate a director of photography. I sympathized with Dante, because he just didn’t have the money to do it.

“When I got there toward the end of prep, I had the crew strengthen the ceiling in certain places, and put in trusses or wooden beams where I needed to place lights. I didn’t see any alternative; we couldn’t light those scenes from the floor.”

The cinematographer says that the Kundun shoot required a very large lighting package. He initially planned to leapfrog his lights from one set to another, but modified this strategy to accommodate a schedule which to some extent reflected the chronology of the script. This meant that the composite Potala set stood for a large part of the schedule, while the appropriate lighting fixtures remained rigged and ready for shooting. Deakins explains, “I didn’t want to be fussing with the lights while the actors were there preparing for a scene. On most of the sets, there were only minimal lighting changes from shot to shot, because I pre-lit the sets using the platforms that had been prepped beforehand.

“I did have a large lighting package, but it wasn’t because I needed a lot of units on any particular set in many cases, I simply couldn’t de-rig one array of lights and get it onto the next set in time to shoot.”

Deakins felt that it would be better and more cost-effective to use tungsten sources on the sets, while maintaining a separate HMI kit for exterior work, night work and the few location interiors. He ordered his basic package from Cartocci in Rome, and made sure to schedule in the two-week delivery time to Ouarzazate. “I wanted to have the equipment in Morocco two weeks before we started shooting so we could do our pre-lights,” he notes. “Working off of Dante’s plans, I came up with an overall lighting package, and I added some extra gear to cover any problems, which I knew we’d encounter at some point.”

The complete lighting package for the Atlas Film Studio stage work included approximately 58 Maxi-Brutes, 32 blondes, 24 10Ks and two 20Ks. “It was probably even more,” Deakins hedges, “and that was just for the stages. We mounted 20 of the Maxis on the wall of our Potala courtyard set, and they stayed there for 10 weeks. We also had to have two generators. I couldn’t have gone much further with the lighting package, because I wouldn’t have had the generating capacity. At one point, we had everything burning, and both of the generators were in trouble! It was right on the edge of what they could handle, and I was still only shooting at T2.5.”

Depending on the scene at hand, Deakins altered his lighting approach for stagebound setups to reflect the appropriate dramatic tone. “The first time we see the Tibetan assembly room is during a sequence in which the young Dalai Lama is walking around the monastery and checking things out,” he relates. “He hears these voices from the assembly room, and when he looks in he sees all of these older men discussing the fate of Tibet in this huge, amazing room. I wanted our first view of the room to be really gray and kind of mysterious, so we used a soft, cool toplight; to get a soft wrap, I installed wide-flood bulbs in a number of Maxi-Brutes. We then bounced these lights off large Griffolyns which we tied to the roof rafters of the ‘stage.’ This light was then softened and cut as it entered the ceiling of the set itself, only 10’ below. It was all a bit of a struggle; I must have lit that particular scene five times before achieving something that I was happy with.

“For a later scene in which the Dalai Lama is meeting with a Chinese general in a French-European-style living room, I wanted more of a low, direct sunlight look. I was basically using the same units, Maxi-Brutes, but I switched to narrow-beam spot bulbs to obtain a harsher look. A light brushed-silk diffusion erased the multi-shadow problem caused by the bulb array. If I was using a Maxi for a different kind of situation bouncing light off a Griffolyn or something I would occasionally install medium-flood bulbs.”

The scarcity of state-of-the-art equipment made the film’s larger night shoots a bit problematic particularly a key sequence in which the disguised Dalai Lama leaves his palace for the last time and wends his way through a throng of people beyond the gates of an ornamental garden. “There are no lifts or Condors in Morocco, and you can’t have a Musco light with the type of budget we had,” Deakins submits. “The only way to do that shot was to build a 60’ tower rig, partly out of scaffolding we managed to find in Casablanca. All of that material had to be brought 400 miles from the coast to Ouarzazate. It took the crew two weeks to build the rig; there was no way it was going to move once it was up, so we basically had to light this entire series of shots with one high source.

“We built the tower in a very specific spot so it would be hidden behind the garden wall when the camera panned, tracked and craned around. I think we had six 12K HMIs up there to create a blue ‘moonlight’ effect. Those were not corrected at all, as I was going for a more colorful look than I normally would at night. We also placed some little oil lamps actually 1K bulbs on dimmers beneath the archway to add some contrasting color to the shots as the Dalai Lama and his companions went through the gate.

“We had an original HMI package of four 12K and four 6K Pars, but for the night shoots we had to bring in two extra lamps from Rome and a couple more 12Ks from this little commercial company in Casablanca. After we finished each night, we had a day crew move everything lights, generators and cables to the next location so that we could maximize our shooting time.”

Smaller tower rigs were used for a subsequent nighttime sequence in which the Dalai Lama departs from Lhasa in a small boat. “We were shooting on an open lake, but it was meant to be a broad river in the story, so I tried to find a spot where I could have the feeling of a far bank. We found a place where the landscape curved so I could have a headland, about three-quarters of a mile distant, in the back of the shot.

“I was shooting wide open at about T2.1 with one of the slower, 32mm Zeiss lenses. It actually worked very well. Of course, if it had been windy, I think I’d have been screwed!”

“I was under some restrictions lighting-wise, because we were shooting on a dirt path by a lake; I didn’t have a crane, and we couldn’t build any large towers down there. Besides, all of the scaffolding we could find in Morocco was already in use at the palace location. When I first thought about lighting that scene, I was going to put all of my lights on a hill and just have a big wash. But then I thought, ‘That’s going to be one hard source, and I’m still going to have to fill faces as I move the camera.’ There were quite a lot of moving shots, and a lot of shots to do [in general], so we didn’t really have the time to mess about. I lit the background with Par lights aimed from the top of a hill, which gave us this gray wash on the far hillside. To light the characters in the boats and on this nearby jetty, I came up with an idea. There was one area of beach that I didn’t have to have in the frame, so I put up four little 10’ towers, each with an 8’ by 8’ reflector on top. Each tower had a 12K or a 6K HMIPar underneath it. Depending on where the camera was, I could line these reflectors up quite quickly to give a somewhat soft directional source. I was shooting wide open at about T2.1 with one of the slower, 32mm Zeiss lenses. It actually worked very well. Of course, if it had been windy, I think I’d have been screwed!”

Deakins notes that the scene was later enhanced by digital artists at Dream Quest Images, who added mountains in the background and stars in the sky. “I looked at some of the test composites, and they were pretty good,” he says. “The trick was to match the lighting of the background plate to my lighting in the foreground. Trouble was, I couldn’t light the foreground with the same quality of light that could be created with the freedom of the computer. The computer-generated background looked softer and better than my foreground, and the difference between the two was a giveaway. To even it out, they had to make the lighting in the background a little more directional and from the side, rather than the beautiful soft moonlight that they started off with.

“There was no way we could have lent that scene a feel of the distant mountains before this sort of technology came along,” he maintains. “We could have done a static bluescreen-type shot, but we’d have been very restricted. Digital technology has really freed us up; my only regret at this time is that we were unable to adjust all of the shots within that scene.”

Thankfully, the film’s daylight exteriors proved to be a bit less labor-intensive. “We basically shot with very hot light,” Deakins says. “I suppose we made an advantage of the fact that we were shooting in midday sun; every day was hot and bright. We really didn’t shoot anything in the morning or evening; I think low, golden sunlight tends to be a bit overused. We used the bright exterior light as a nice contrast to the interiors of these monasteries, which are naturally very dark.”

Because Morocco’s altitude is not as high as Tibet’s, Deakins found himself dealing with the country’s dustier atmosphere on exterior shots. “I tried to get rid of that with Pola screens, and I didn’t filter anything because I wanted to keep everything as sharp as possible. There isn’t a single diffused shot in the film; I did use the odd grad, but not too much.”

Deakins did make frequent use of gels on his lights, however. His use of color is illustrated by a scene in which the Dalai Lama moves through a snowswept passageway and enters the Throne Room, which was decorated with a huge golden statue of the Buddha and cylindrical cloth tapestries known as thangas. Within this majestic space, the young boy is officially enthroned.

The passageway in question underwent several changes during the course of production. In addition to serving as the entrance to the Throne Room, it also doubled as a corridor in both the Potala Palace and Dungkhar Monastery. The passage was open to the elements on each side, and also featured three skylights along its 70’ length one large opening, and two smaller versions. “If I had been in a studio, I probably would have put a big white bounce cove above the skylight and bounced the light from outside the set walls,” Deakins says. “There was no way I could do that on this show, because there was no place for me to rig that kind of setup. I talked about that with the key grip, Tommaso Mele, but it would have involved rigging up this huge construction, and the wind probably would have blown the whole thing down. There were 20 miles of flat desert on either side of our corridor, and every afternoon at three o’clock, 50 mile-an-hour winds would come howling across the desert, blow our lighting frames away, completely trash my rigs and fill the whole corridor with dust! In the end, we erected a more modest grid above the skylights a wooden truss surrounded by some piping. The only way to get the look we wanted was to hang Maxis above the skylights. We had six Maxis over the biggest skylight and two over each of the smaller openings. The Maxis generally had 1/2 CTB on them, and the mixture of this light and the natural daylight that percolated through these openings was further softened and corrected by two layers of 250 diffusion and 1/2 CTO gel.

“For the scene in question, however, I wanted the passageway and the Throne Room to offer sharply contrasting color temperatures. We had a snow effect coming from overhead in the passageway, and the floor was covered with piles of the stuff. For that part of the sequence, I created a cooler look by removing the 1/2 CTO gel on the skylights. The mixture of 1/2 blued tungsten and raw daylight from above looked great on the fake white snow, and heightened the dawn effect.”

The Throne Room, by contrast, was lit to be completely warm. When the Dalai Lama reaches this area, he discovers a crowd waiting to witness his coronation. “The people were sitting on benches, facing the Buddha,” Deakins recalls. “It was going to be hard to light the set from below, and the roof of our ‘stage’ wouldn’t hold very much weight. I rigged up a bunch of lightweight 10Ks on dimmers, just hoping the room could take them. These lamps were bounced off some 8’ by 8’ gold reflectors positioned in the rafters. Each lamp carried 1/4 CTO and was dimmed to about 60 percent to create a warm, golden look. I also positioned gag lights behind butter lamps on the floor 1Ks or 500-watt bulbs dimmed down to around 2200°K.

“Of course, we could have lit everything straight tungsten and printed warmer, but I never think that really works as well. When you do something like that, you’re exposing the emulsion in the wrong balance. Attempting to change that balance in printing will only alter the contrast and grain in the final print.

“When I’m told about a set, I draw it out and sort of sketch in what I think I should do,” he adds. “On that particular set, I thought I was going to use a direct-light effect, but when I looked at the actual space, I decided that I wanted it to be a bit softer, so I wound up bouncing all of my lights.”

Deakins says that the nature of the shoot, and its authentic sets, led the filmmakers to use Steadicam more often than expected. Although Scorsese has used this device sparingly in the past (mainly for meticulously staged sequences like the bravura tour of the Copacabana club in GoodFellas), he and Deakins decided to take advantage of English operator Peter Cavaciuti’s considerable expertise. “Prior to shooting, when Marty and I went through the script and talked about camera moves, there were only two preplanned Steadicam shots. I had worked with Peter on The Secret Garden, though, and I knew he was a great operator; I had a feeling we’d be using him more on the actual shoot. We eventually worked out that he would be there the whole time, and we also negotiated to have his equipment there all the time. Once Marty saw how good Peter was, he gained an enormous amount of confidence in him. The moves didn’t have the floaty feeling that Marty doesn’t like; when Peter ends a move, it’s rock-solid.

“The sets, by their nature, were built to look very real,” he points out. “The floors were stone; we couldn’t do the old trick of pulling the rails away as the camera passed by, because there was no place for the people to get out of the way in these narrow corridors. Quite often, the only way we could do a sequence was with the Steadicam and the Moviecam SL.”

The value of the Steadicam is illustrated in a key scene near the end of the film, when the Lord Chamberlain informs the Dalai Lama that foreign governments have refused to support Tibet as an independent nation, in effect siding with China. The sequence was blocked out as a Steadicam shot that would move backwards as the two characters walked through a long, winding corridor and into a study, where other Tibetan noblemen awaited them. “That sequence was initially broken down into a lot of different shots, some involving the Steadicam,” Deakins notes, “but we wound up doing one Steadicam shot walking backwards in front of the guys, and another little piece of Steadicam over their shoulders as an intercut.

“We pre-lit the entire corridor for that,” he explains. “There were some small side windows in this monastery set, and we also had several skylights to work with. The whole thing was lit in this soft, gray, cool and naturalistic way. I didn’t use a lot on the floor at all, although I occasionally put some butter lamps down there with gag lights around them. We used big soft sources like Maxi-Brutes for the overall lighting through the windows. You need a big soft light outside the window so it wraps through the window; if you put a small unit directly through the window, you’ll just get a shaft of light in one spot. Outside the windows I’d have a 20’ by 20’ light gridcloth with a row of Maxis going through it. The scene started off in darkness, lit just by butter lamps, and then the actors went through this side light from a little terrace area, which became a backlight as the camera pulled back. Next, they passed beneath a little skylight; we had some Maxi-Brutes aimed down through a gridcloth and then through another, lower piece of diffusion to provide a really soft toplight. After moving down some steps, the actors came into this much bigger and softer toplight source. Ironically, it can sometimes take longer to set up if you’re trying to do something naturalistic, because you have to use more light! You’re not trying to be stylized with fewer units and some hard shadows.”

For other scenes designed to simulate the young Dalai Lama’s POV, the Steadicam was used in low-angle mode. “A lot of the film is seen from the child’s point of view. We did a lot of the earlier scenes with our main camera, an Arri 535B, at a really low angle, and we also followed him quite a bit with the Steadicam. We used other motion systems to get that effect as well. There’s a big scene where the boy is pronounced to be the new Dalai Lama in this outdoor ceremony under a tent. All of the people from the surrounding countryside have come to see him, and he walks down this red carpet with rows of people along either side. Marty wanted one POV shot that started on the blue sky and then tilted down past the tent and this throne, which are glimpsed in the distance. The shot continues down until we see the kid’s feet walking along the carpet, and then it tilts back up again to reveal these people looking at him. We had the camera offset on a little PowerPod remote head on an Aerocrane jib arm, and we used a slightly wider lens to catch all of the people in the frame.”

To lend a dreamlike effect to certain scenes involving the Dalai Lama’s point of view, Deakins executed a number of old-fashioned speed/aperture changes with his camera of choice, the Arri 535B. “It’s harder to do than a shutter change, but I liked the idea of doing those shots with a stop change,” he says. “If you change the running speed of a 535A, the shutter will change to compensate the exposure, and it doesn’t affect the depth of field; when you change the aperture, it does. I like slow motion where you’ve got a very shallow depth of field, because it sort of isolates the thing that’s slow in the frame.”

Reflecting upon Kundun’s overall visual style, Deakins notes, “This picture really isn’t an epic; it’s more of an intimate look at the life of an extraordinary person. During the prep period, Marty and I talked about The Last Emperor a bit, and how it was so vast and overpowering. I hope that our film is somehow more naturalistic and earthy. The story is really about the child, and it’s seen primarily from his point of view. We generally didn’t show much that he didn’t experience firsthand. The invasion of Lhasa, for example, is mostly heard in the distance; we do have some shots of Chinese soldiers marching along, but that’s it. As the Dalai Lama grows older, he becomes more aware of the political situation around him.

“In general, I used a lot of sidelight and toplight on this picture,” he adds. “I started off thinking about creating shafts of sunlight through windows, but quite honestly, it was just impractical. Instead, I chose specific scenes that I would light hard; there are some scenes where people are sitting and talking amid this light that is just blasting in. Overall, though, the lighting is less showy and more subdued.

“Working on this show reminded me of some of the documentaries I’ve worked on,” concludes Deakins, whose work on Kundun earned him awards for Best Cinematography from the New York Film Critics Circle and the Boston Society of Film Critics. “It was a bit like camping: we just had to make sure we took everything we were going to need! We had a complicated schedule, difficult sets, and a remote location. But in the end, I’m very pleased with what we accomplished.”

Deakins earned Academy Award and ASC Award nominations for his outstanding camerawork in Kundun. He was later honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2011.

For his contributions to Kundun, Ferretti earned Oscar nominations for Best Art Direction-Set Decoration (shared with Francesca Lo Schiavo) and Best Costume Design.

The documentary In Search of Kundun with Martin Scorsese (1998) further chronicles the filmmaker’s interest in and friendship with the Dalai Lama.