Filming the I Love Lucy Show

The weekly CBS-TV comedy show filmed in Hollywood sets pace for top-quality television.

By Leigh Allen

If there is a revolution imminent in the production methods of motion picture making in Hollywood, it probably is taking place these days on Stage 2 of General Service Studios, where Desilu Productions, Inc. is turning out 22 minutes of TV program film in 60 minutes of actual shooting time.

Major film producers could take a lesson from this company which, like other makers of television films, was in the beginning faced with the problem of how to make films economically and at the same time successfully entertaining for the new medium. That Desilu is succeeding in this is evident in the fact the company is operating at a profit, and that its product, the I Love Lucy television show, is rapidly climbing toward the No. 1 spot in the national polls; at this writing, the show already is No. 4 in the ratings.

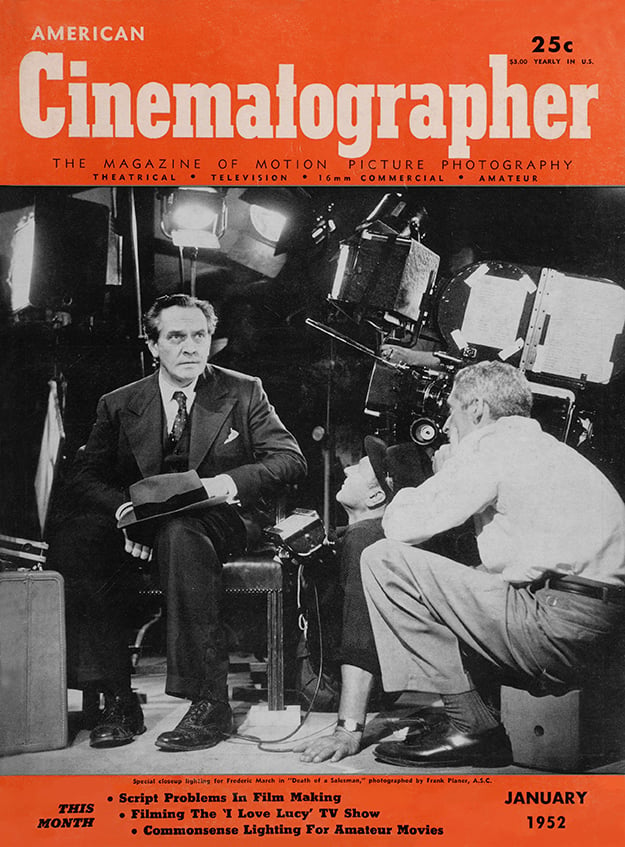

From the point of picture quality, technical men rate the show one of the best of all filmed TV shows. Credit for this is due to Karl Freund, ASC, who is directing the photography.

With the steady rise in popularity of the show, the photographic methods employed by Freund and his camera crews are creating widespread interest among producers of motion pictures—both major and television. Production executives from nearly every Hollywood studio have “scouted" the show during filming and have lauded Freund for his achievements.

Visiting the sound stage during a rehearsal or an actual filming of a I Love Lucy show, one is impressed by the methods and by the orderly manner in which production proceeds. There are none of the interminable delays which mark the production of films in the major studios. Delays could not be tolerated because the show must proceed much the same as an actual live show telecast, inasmuch as there is an audience also present on the stage. This audience is an important adjunct to the show and its audible reaction as the show unfolds is recorded simultaneously with the dialogue and becomes an integral part of the production.

The action in each weekly episode of I Love Lucy takes place on three basic sets erected more or less permanently on Stage 2. The sets, which represent the apartment of Lucy and Ricky Ricardo (Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball), consist of kitchen, living room, and a third room which is dressed as required. The sets adjoin one another and are, in fact “intercommunicating,” so that action, such as a player entering the living room from the kitchen door, becomes a natural thing; and when the continuity of such action is to be picked up by the cameras, they are merely moved before the adjoining set and filming is resumed in a matter of seconds, as will be described later in more detail. Beyond this three-set arrangement is still another set representing the nightclub where Ricky Ricardo is employed as entertainer. Here the orchestra is assembled for every show, whether or not it is to be used in the picture filmed that evening.

The show goes before the motion picture cameras in much the same way it would as a live show in a television studio. Indeed, as Freund points out, the almost continuous camera on dolly technique employed is adapted from standard TV camera operations for live shows.

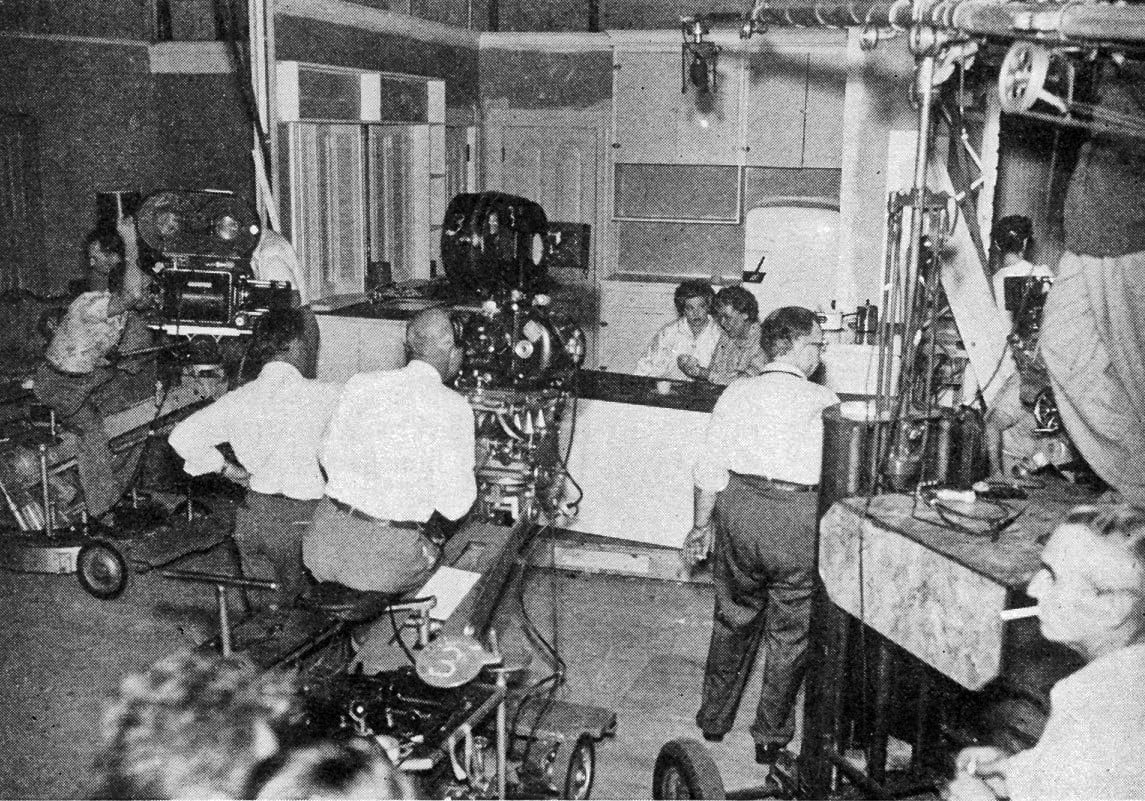

The show is photographed on 35mm film with three Mitchell BNC cameras mounted on dollies, as shown in the photos. All three cameras shoot the action simultaneously. The camera in the center makes all the long shots with a 40mm wide-angle lens. The cameras at either side record the action in closeups, using 3-inch and 4-inch lenses. In the beginning, the company used a cue-track method, which permitted remote control operation of the cameras individually for long shot, medium shot, and closeup, as the script demanded. This system was soon abandoned, however, in favor of regular film production methods, with the takes from the three cameras edited on the Moviola, etc. The result is greater speed in the photography of scenes and better results in the final editing.

Cueing of camera operators, grips operating the dollies, and of the gaffer handling the light dimmers is still a major function in the production of the weekly films. When the show is being photographed, the script girl in a booth overlooking the stage is in direct contact with the key technicians at all times via two-way intercom phones. Although each man previously is briefed on the operation and in many cases has floor marks to guide him, the script girl insures against any possibility of error by her timely cues. Impressive is the speed with which the crews move on to the next setup and start shooting again. A special check made of this operation showed that elapsed time between camera setups averaged a minute-and-a-half.

A major factor making such speed possible is the lighting arrangement worked out for the production. Since invariably the players are in action over almost the entire set, the light intensity must be uniform over the entire area at all times. There are no light changes, other than those made by dimming. All set illumination, therefore, is from overhead. There are no floor lamps and the only illumination from a lower level comes from the portable fill lights, which are mounted just above the matt box on each camera. The set lamps are rigged on catwalks, which are suspended above the sets. The light units consist of Seniors and converted Pans with spun glass diffusers added. The overhead lighting scheme keeps power cables off the floor and makes feasible the unobstructed operation of camera dollies as well as quick movement of camera equipment to the subsequent setups.

“To light a set for three cameras operating simultaneously and from different positions is a problem in itself,” Freund said. “We have to light as uniform as possible, yet watch for opportunities to add highlights whenever we can. This is highly important, inasmuch as it is a comedy show requiring high-key illumination."

“Contrast also has to be watched carefully, since the tube in the film image pickup system of the television station is quite contrasty. Any contrast in the film therefore is compounded if not exaggerated in each step of the transmission of the picture. This makes it necessary to keep the contrast in the original negative down to what we call a ‘fine medium.’”

This knowledge of the contrast secret is further revealed in the decor of the sets. These are painted in various shades of grey. Props likewise follow the ethical demands of correct contrast, as do the wardrobes of the players. Even newspapers, when they are to appear in a scene, have to be tinted grey. Such overall uniformity of colors or tones in the scenes make rigid demands on the lighting and has resulted in the careful illumination formula which Freund and his gaffers now regularly employ in lighting the sets. Although each weekly show goes before the cameras at 8 o’clock Friday evenings, and is photographed entirely the same evening, the preceding four days are employed by the company in rehearsals, pre-production planning and script revision. The camera crews have but two schedules in the five-day period — on Thursday and Friday.

The director, actors, and writers gather on the stage for a reading of the script on Monday and Tuesday; late Tuesday afternoon the first of the rehearsals are held. By Wednesday afternoon, the company is ready to run through the show for Freund. This usually takes place at 4:30. No cameras are on the set at this time, nor are any members of the camera crews present. During this rehearsal, Freund studies the players in their movements about the sets, takes note of how and where they enter and exit, and plans his camera operations and lighting accordingly.

The following morning at eight o’clock Freund and his electrical crew begin the task of lighting the sets, and endeavor to have the job completed by noon. At this time, the camera crew members come on the set and are briefed on camera movements, etc. With the crews and cameras assembled on the stage, camera action is rehearsed. This enables Freund to make any necessary changes in the lighting or operation of the camera dollies. Cues for the dimmer operator are worked out at this time. Chalk marks are placed on the floor indicating the positions the cameras are to take for the various shots or the range of the dolly action for a given scene.

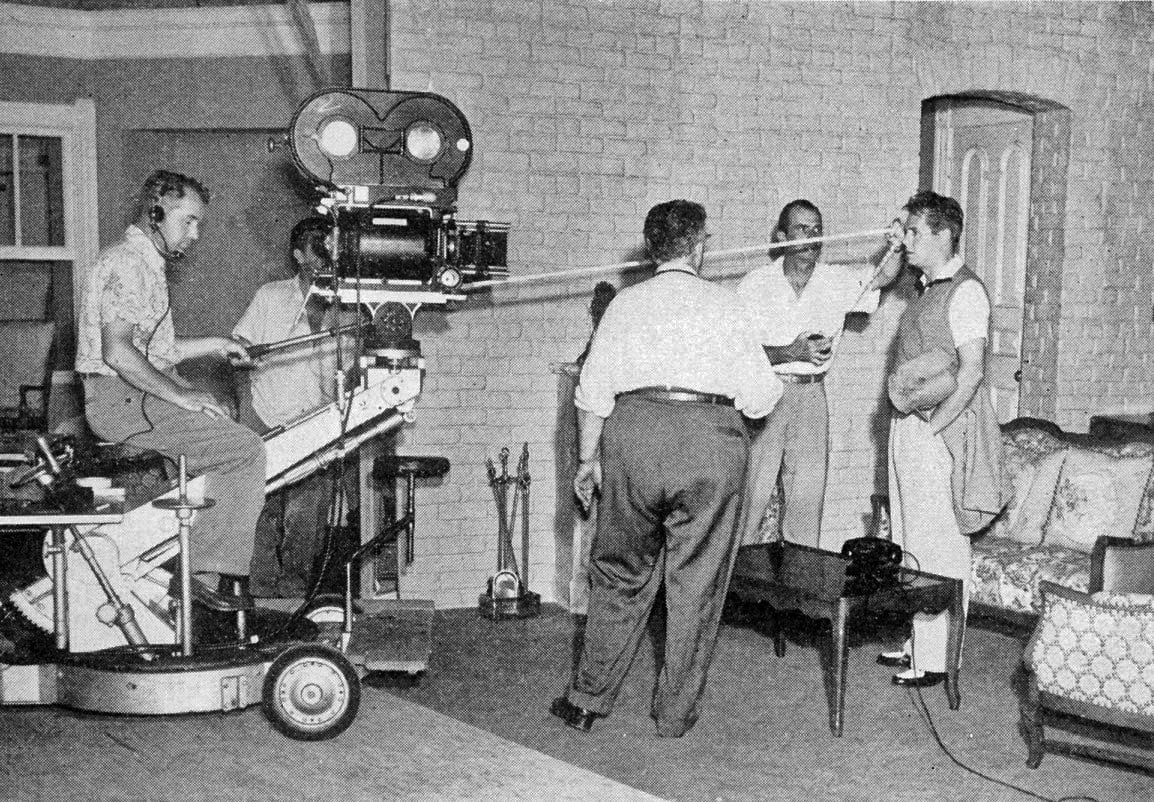

assistant runs a tape from camera to Arnaz during a camera rehearsal. Weekly

production employs three complete camera

crews, supervised by Freund.

At 4:30 P.M. Thursday, there is another rehearsal — this time with the camera crews, gaffers, sound men, etc., on hand. Then at 7:30 the same evening a dress rehearsal is held. Freund, camera operators, gaffers and grips are on hand — but the cameras are not brought on the door. At this time the general plan of the show is discussed by the director. Notes are made for future guidance by all present. An open discussion then follows at which time lines of dialogue are cut, action shortened or deleted, camera movements analyzed in short, everything is done at this time that will tighten up the show and improve its pace. This is the period in the pre-production planning when problems are aired and suggestions made and considered.

On Friday, when the show is scheduled to be shot, there is a 1:00 P.M. call for everyone in the company — players, technicians, the producer and the director and his staff. If any major changes in the action, dialogue or camera treatment were decided in the previous evening’s discussions, these are now worked into the show during another general rehearsal. A final dress rehearsal takes place at 4:30 P.M., with the cameras now on the floor. Freund gives his lighting a final check, makes any necessary last minute changes before the company breaks for dinner.

After dinner, company and cast return to the stage, and there follows a general “talk through" of the show. At this time, further suggestions are considered and decisions made on any remaining problems, so that by 8 o’clock the company is ready to film the show.

In the meantime, the audience seating on the stage has rapidly filled and Desi Arnaz or some other member of the company is briefing the audience on the show, explaining the filming procedure, and emphasizing the importance its natural, spontaneous reaction plays in the show’s success.

Then, for approximately 60 minutes, the show is filmed. As soon as action is completed for one setup, the cameras, crews and players move rapidly to the next setup, and the action is resumed. All scenes are shot in chronological order.

As is to be expected, where a production receives such meticulous planning and thorough rehearsals, retakes are seldom necessary. In this respect, each camera operator has a major responsibility. He must get each take right the first time — every time. Of course, he can hardly miss, considering the careful preparation that went into the filming phase of the production beforehand. Focus was carefully measured and noted for each camera position; chalk marks were placed conspicuously on the stage floor; there were the numerous rehearsals, and of course there is the vigilant script girl overlooking the proceedings, relaying instructions over the intercom system.

In the beginning there was a very definite reason for the decision of Desilu Productions to put the I Love Lucy show' on film instead of doing it live and having kinescope recordings carry it to affiliate outlets of the network. The company was not satisfied with the quality of kinescopes. It saw that film, produced especially for television, was the only means of insuring top quality pictures on the home receiver as well as insuring a flawless show. “Putting a show on film, you can plan and cut, which you can’t do with a live show,” Freund explained. "Also, you avoid the fluffs which are bound to happen in live shows. But most important, if the film doesn’t look right after it’s edited, you can re-shoot scenes, and add others to improve the picture, if necessary.”

A question frequently-asked is why — as long as the show is filmed, the same as a theatrical film— does the company employ three cameras instead of only one, as do the major studios. The answer is that the I Love Lucy show must retain the illusion and the effect of immediacy of a live TV show. For this reason it must be filmed before an audience, and this makes it necessary that the production unfold as continuous as possible, much the same as a stage play, with only two or three interruptions — as on the stage when there is a pause between acts. This makes it necessary to shoot the various long shots, medium shots and closeups all at the same time in order to provide the film cutter with the desired takes for editing.

The three cameras shoot an average of 7,500 feet of 35mm film per show. The filming procedure, as presently followed. Freund pointed out, is far less costly than major studio film production. One of the first significant moves by Desilu Productions was to surround its stars with the best technical and creative talent — ideally illustrated by its decision to sign Freund, dean of cinematographers, to direct the photography of I Love Lucy shows. Freund is one of the few cinematographers active today who saw the start of silent pictures, of sound films, of color photography, and now television films — and who had a hand in the development of each. To accept the Desilu assignment was to accept the challenge of obtaining the quality of film image demanded of television films, despite the technical handicaps understandable in a new industry.

“What we are striving to do,” says Freund, “is establish a standard that will please the television industry. At present, it is useless to try and improve further the photographic quality of TV films until the industry is ready for it — that is, until there is further technical improvement in the various electronic components of the television system. Already, in recent months, the industry has made great strides in this direction, with considerably improved picture quality from TV films now evident.”