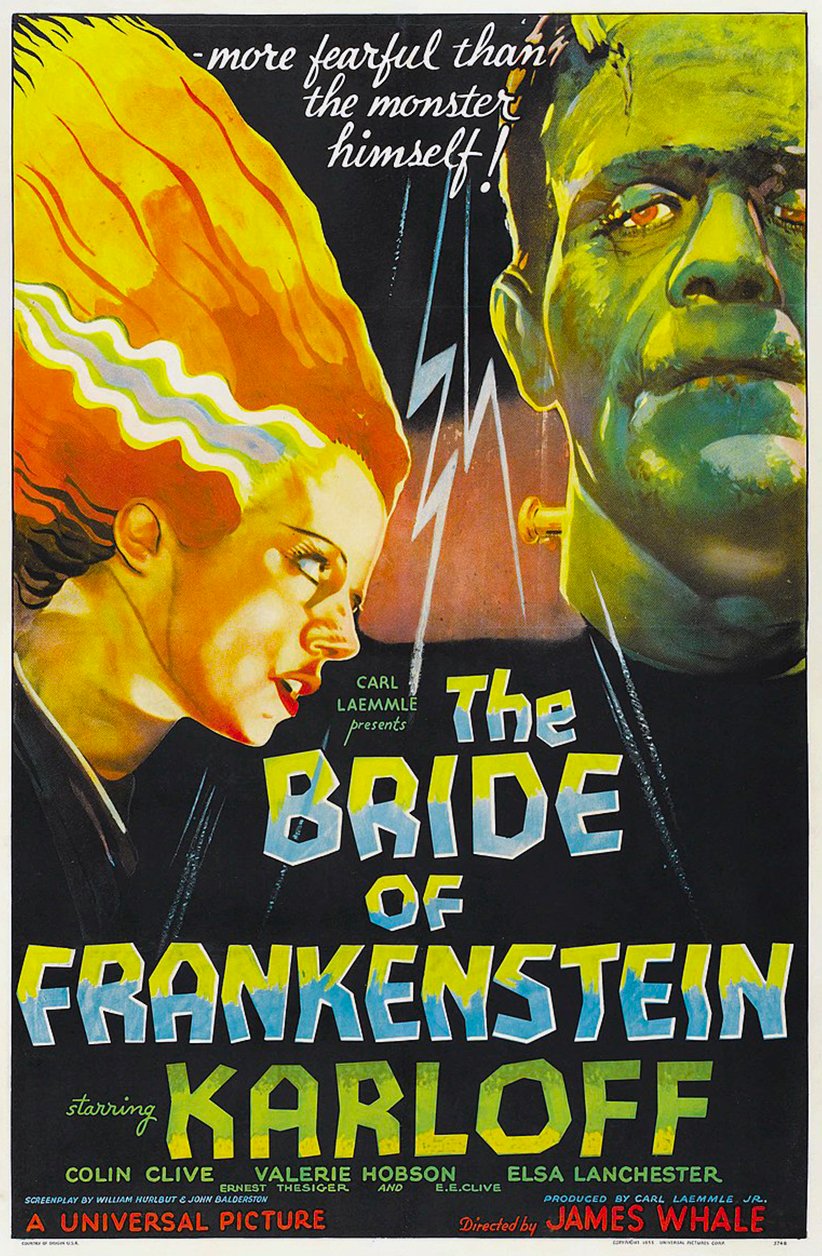

The Bride of Frankenstein: A Gothic Masterpiece

Director James Whale and an expert team of cinema artists defied the odds in creating a memorable sequel to one of the most famous monster movies of all time.

This article was originally published in AC Jan. 1998.

By Jan A. Henderson and George E. Turner

"To a new world of gods and monsters!" toasts the mad Dr. Pretorius, triumphantly raising a beaker of gin. It is a legendary moment in The Bride of Frankenstein.

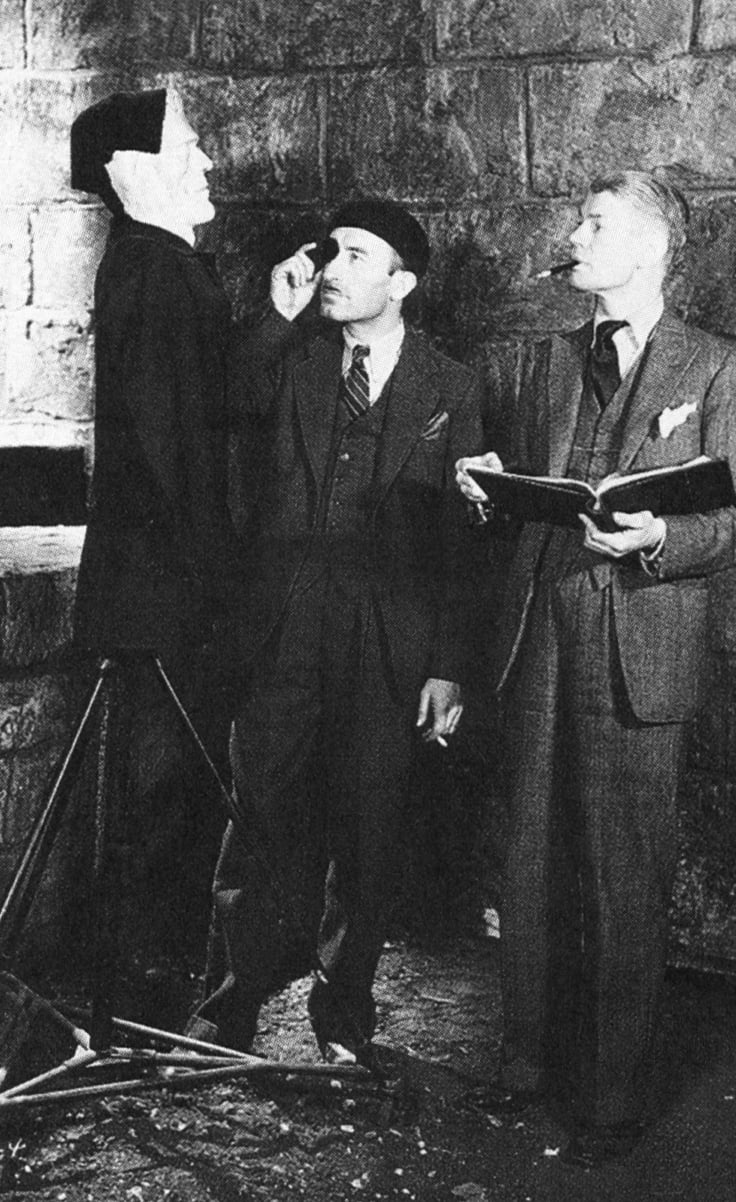

On January 2, 1935, when production on the film began at Universal Studios, director James Whale should have offered the same toast to his collaborators the writers, actors, cinematographers, designer, editor, makeup artists and composer. These were key figures in crafting this Citizen Kane of fantasy films.

Bride is a sequel to Universal's 1931 hit Frankenstein. The axiom that sequels are never as good as the originals generally holds true, but there are exceptions: Tarzan and His Mate, After the Thin Man, From Russia With Love, The Godfather Part II and The Empire Strikes Back, for example. It is widely conceded that Bride is one of these successes, although not everyone agrees. Even Whale and his star, Boris Karloff, preferred the original, which represented a crucial turning point in their careers. Karloff argued that it was a mistake in the sequel to have the Monster speak, that too much sympathy was built up for the Monster, and that the use of musical scoring was intrusive. (Frankenstein has often been criticized for its lack of music by modern writers who fail to consider that in 1931, background music was considered an outmoded artifact of the Silent Era.) Some lovers of horror films prefer their horrors unleavened by humor.

After the success of Frankenstein, Universal quickly announced The Return of Frankenstein for the 1932-’33 season. Whale was adamant that he wanted no part of the project. The New Adventures of Frankenstein, a treatment by a Frankenstein scenarist, Robert Florey, was rejected in February of 1932 by the youthful studio chief, Carl Laemmle, Jr. In 1933, director Kurt Neumann, a Laemmle protege from Germany, was put in charge of developing the project as a vehicle for Karloff and Bela Lugosi. Scenario editor Tom Reed wrote another treatment, and Philip MacDonald, Edmund Pearson and Lawrence G. Blochman were among the distinguished authors who became involved. Playwright John L. Balderston, author of Berkeley Square and co-author of Frankenstein, created a prologue involving Mary and Percy Shelley and Lord Byron. The bulk of Balderston's treatment, in which the Bride is created from the oversized head of a circus freak and women's body parts rifled from train wrecks, was deemed too gruesome for consideration.

Meantime, numerous writers were trying unsuccessfully to deliver a satisfactory screenplay of H. G. Wells' The Invisible Man. Whale persuaded Laemmle to offer the assignment to a friend of his in London, R.C. Sherriff, an Oxford don who had authored the successful play Journey's End. As planned, Whale asked to direct Sherriff's adaptation (arguably the finest fantasy script of the decade) instead of the Frankenstein project. He insisted that Junior Laemmle take the script home, and, after a good dinner, read it in its entirety. He was aware that this request would irritate Laemmle, who never worked after his evening meal. In his autobiography, No Leading Lady, Sherriff writes that Whale told him, "If they score a hit with a picture, they always want to do it again. They've got a perfectly sound commercial reason. Frankenstein was a gold mine at the box office, and a sequel to it is bound to win, however rotten it is. They've had a script made for a sequel, and it stinks to heaven. In any case, I squeezed the idea dry on the original picture, and never want to work on it again."

Whale would eventually relent, however. By early 1934, having made six successful movies (The Impatient Maiden, The Old Dark House, The Kiss Before the Mirror, The Invisible Man, By Candlelight and One More River), the director had a change of heart. Assisted by Sherriff, he began preparing the Frankenstein sequel from scratch. Sherriff became homesick and soon returned to Oxford. Whale then worked with Balderston and William Hurlbut, author of the play Lilies of the Field. Whale began casting the picture while the script was being written, and had alterations made to accommodate his actors of choice. Balderston angrily demanded that his name be removed from the screenplay, but was still given credit (with Hurlbut) for the adaptation.

The script met with severe opposition from Joseph Breen, administrator of the Production Code. Whale wrote a solicitous letter assuring him that any depiction of necrophilia, gruesomeness and religious images would be modified to suit the demands of the Code.

Universal planned to reunite the principals from Frankenstein, but only the indispensable Karloff, Colin Clive and Dwight Frye were called. Frye was supposed to resume his role as Fritz, Dr. Frankenstein's half-witted, hunchbacked assistant. However, Whale departed from the script and cast Frye as Karl Glutz, the village murderer, and later sent Karl on Fritz's horrid errands. English actress Valerie Hobson, then 17, was given the former Mae Clarke role as Elizabeth. For the role of the blind hermit who befriends the Monster, Whale wanted Australian actor O. P. Heggie so badly that he rescheduled Bride so Heggie could finish a picture (A Dog of Flanders) at RKO.

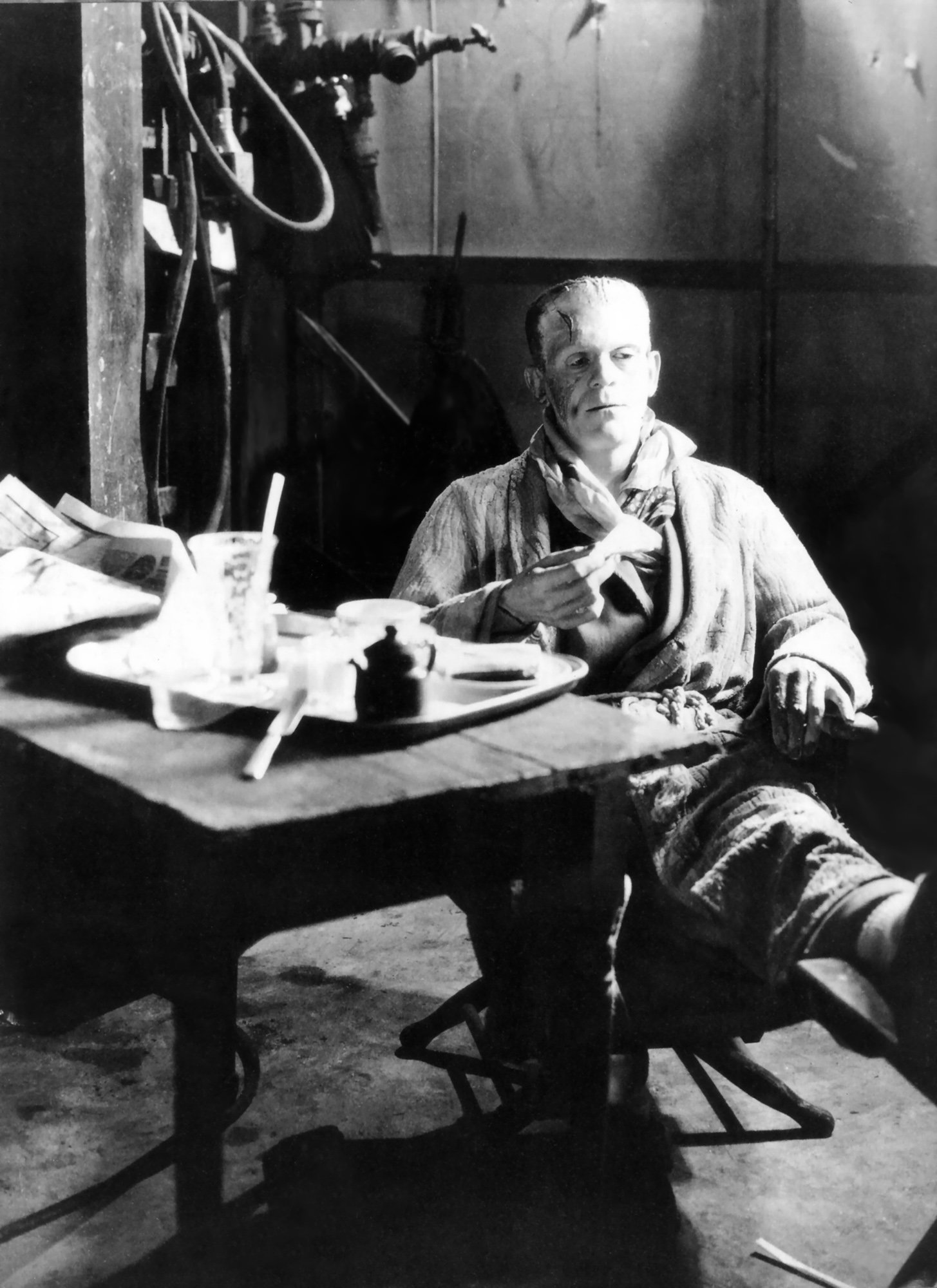

Karloff had reservations about reprising his most famous role. He rarely complained about the physical ordeals the part demanded, but in a 1958 radio interview with Clive Edwards in Carmel, California, he recalled the rigors of making the first film: "The makeup took about four hours to put on I worked every day on the film, the film took eight weeks to make, and I remember one awful occasion when I got into the makeup shop at half past three in the morning, to be ready to go out on location. We worked in the hot sun at the edge of the lake, the scene with the little girl. We came back to the studio in the evening to have some supper, and we went out onto the backlot and I worked all night until five in the morning. I had the makeup on for 25 hours! That was a long pull. The carbon lights were dreadful. They hurt your eyes. The boots weighed about 16 pounds apiece. All told, the outfit weighed between 40 and 45 pounds." Acting in the costume further damaged Karloff's back, which he had injured years before as a laborer loading cement for Eastman Building Supply in Hollywood.

Claude Rains, Whale's star discovery from The Invisible Man, owed the studio a picture and was slated to play an eccentric new character, Dr. Septimus Pretorius. Instead, Rains was assigned to The Mystery of Edwin Drood, whereupon Whale sent word to England for an old friend from the London stage, Ernest Thesiger.

Phyllis Brooks, Arletta Duncan and international star Brigitte Helm were considered for the title role, but Whale brought in another Britisher for the part: Elsa Lanchester, the redheaded wife of Charles Laughton. A small but voluptuous woman with a fey kind of beauty and a ribald sense of humor, she also played the fragile Mary Shelley in the prologue. This was Whale's way of showing that even sweet Mary harbored a monster within. Whale and Thesiger designed the makeup for the Monstress, basing the idea upon the famed sculpture of Egyptian Queen Nefertiti, with long hair streaming upward. Makeup artist Jack Pierce brought the concept to life. The Bride initially seems beautiful, but her eccentric animation, stitched-together neck, and uncouth screams and hisses quickly dispel this impression.

From Dublin's Abbey Players came tiny, birdlike Una O'Connor, whose piercing shrieks echo through The Invisible Man, to play the even noisier Minnie.

The sequel uses its predecessor as a springboard in bringing forth several latent ideas from Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's original 1818 novel, and develops unpredictable new angles. Whale's penchant for black humor, which surfaced sparsely in the 1931 film and was developed with increasing sophistication in The Old Dark House (1932) and The Invisible Man (1933), is pushed to the limit in Bride, transforming what could have been a downbeat narrative into a multilayered entertainment.

Bride of Frankenstein begins in 1818, after the publication of Frankenstein. In a storm-buffeted castle, where Percy and Mary Shelley and Lord Byron are discussing her book, Mary moves the plot forward: at the burning mill, Minnie, the Frankensteins' maid, leads the crowd in celebration. The burgomaster orders Henry Frankenstein's body borne home and shoos everyone away, but Hans and his wife, the parents of a child drowned by the Monster, remain. Searching the ruins, Hans falls into the cistern beneath. The Monster, emerging from the shadows, drowns him and hurls his wife into the pit. The Monster then encounters Minnie, who runs screaming to the castle. Upstairs, the ailing Baron Frankenstein dies, but it is discovered that Henry is alive.

The convalescing Henry is visited by his former university professor, Dr. Pretorius, who wants Henry to help him "probe the secrets of life and death and reach a goal undreamed of by science." Taking Henry to his rooms, he shows him seven humanlike creatures less than one foot tall, which he "grew, as nature does, from seed." Henry wants no more of "this hell's spawn," but is intrigued when Pretorius suggests that they create a woman.

The Monster, wandering the woods, startles a shepherdess, who falls into a pool. He rescues her, but her screams attract two hunters, who shoot him in the arm. He flees, but is captured by a mob and chained in a dungeon. The Monster quickly breaks free and smashes through two heavy doors as the villagers run away. He rampages, killing men, women and children. In the forest, he enters the cabin of an elderly blind hermit, who treats him kindly and invites him to stay. As weeks pass, the Monster's friend teaches him to talk, but hunters eventually arrive and try to kill the creature.

With another mob at his heels, the Monster stumbles into an underground crypt, where he sees Pretorius and his helpers open the coffin of a young woman. Pretorius remains and unpacks his lunch. When the Monster emerges, Pretorius welcomes him, gives him food, wine and a cigar, and says he wants to create a mate for him. When Henry refuses to help, the Monster kidnaps Elizabeth, Henry's bride. Pretorius says she will be returned when the experiment is completed.

In the watchtower where the Monster was created, Henry, Pretorius and two murderers, Karl and Ludwig, work feverishly on the new creation. Karl murders a young woman to procure a stronger heart. The Monster, enraged at being put off, throws Karl from the tower. Meanwhile, the female creature comes to life. When the Monster approaches her, she screams in terror. Filled with sadness, he sends Henry and Elizabeth away, then pulls the lever that will blow the tower to bits. Pretorius and the Monsters are buried in a series of explosions.

Whale retained most of the religious imagery that had worried Breen. The captured Monster, raised aloft on a pole and pelted by rocks, obviously symbolizes crucifixion. Additionally, a crucifix in the hermit's cabin is heavily emphasized; the Monster angrily topples a statue of a bishop; and Pretorius impiously quotes Biblical phrases ("Male and female created He them. Be fruitful and multiply."). Elizabeth tells Henry that his thoughts are "blasphemous and wicked." While these touches are much commented upon by historians, no one has explained why Pretorius dons a yarmulke before unveiling his miniature creatures.

Bride of Frankenstein was entirely made on the Universal lot, allowing the designers to create a world of their own. With the exception of the street scenes in the backlot village, everything was filmed on soundstages. Charles D. Hall's settings are vividly atmospheric, with exteriors suggestive of Gustave Dore's demonic woodcuts. Hall expanded the scope of the burning windmill and the watchtower laboratory from Frankenstein enormously and redressed the crypt from Dracula. Among the more impressive sets are a blasted forest with towering, limbless trees and strange rock outcroppings, a waterfall and pool in a verdant forest, a peasant hut in the tradition of Grimm's Fairy Tales, and a hillside graveyard studded with leaning monuments. These "exteriors" are backed by gigantic sky cycloramas. The roof of the watchtower was filmed against a black backing so that a roiling, lightning-streaked sky could be matted in.

The grandest interior is the new version of Castle Frankenstein, which includes a huge central hall with groined arches and tall pillars, and large rooms with vaulted ceilings, ornate windows, heroic tapestries and massive furnishings. The laboratory is supposedly the one in which the Monster was created, but it is actually much larger, 70 feet high and more elaborate than the original setting. The refurbished space is filled with fantastic machinery created by Kenneth Strickfaden, the electronics genius who had furnished the lab equipment for Frankenstein. Another key set is a vaulted underground dungeon where the Monster is shackled to a massive chair while villagers peer down from a street-level window. Other impressive sets include the cistern and waterwheel underneath the mill, the crowded interior of the hermit's hut, Pretorius' strange apartment, a mountain cave, a morgue, a courtroom and village homes.

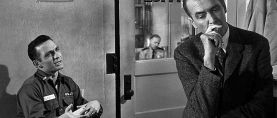

The cinematography of John Mescall, ASC highlights sets and players to maximum effect. He worked well with Whale on five movies (including By Candlelight and One More River), setting up rapidly and never troubling the director with trivial details. In the village scenes, he captures the ambiance of an inbred community with a disproportionate share of demented misfits. As Mary Shelley begins her story, the camera dollies away swiftly. Several times the camera follows action past walls. The Monster and Pretorius are often shot from low angles to make them seem abnormally tall. During the creation sequence, the scientists' fanaticism is emphasized by the rampant light on their faces and a succession of oblique camera angles.

Universal executives were concerned about Mescall's participation in the project because the cameraman was a chronic alcoholic. Apparently, his artistry did not suffer when he was drinking; the problem was getting him to and from work. During the 1940s he was often replaced after failing to report for duty, yet earned a Best Black-and-White Cinematography Academy Award nomination in 1942 for Take a Letter, Darling. Although he made no secret of his addiction, Mescall had a distinguished career and was also a world-class golfer. He lived his last years in obscurity.

Special effects photographer John P. Fulton, ASC also lent his talents to the show. A Swedish-American from Nebraska, John was the son of matte artist Fitch Fulton; he had worked on all of Whale's Universal pictures. He often argued violently with studio bosses, directors and cinematographers. Aided by David S. Horsley's optical photography and Charlie Baker's miniatures, Fulton created unprecedented effects for Bride. The picture's miniatures, the mountain castle of the prologue, the burning windmill and the watchtower are excellent. The destruction of the tower is fully convincing due to the detailed construction with individual building stones, masterful lighting, controlled pyrotechnics and high-speed photography.

Virtuoso effects depict Pretorius' seven miniature homunculi in their glass jars. Fulton and Horsley were on the set for two days during live-action filming. Careful measurements were made of camera elevations, distances and angles, as well as the sizes of the jars and other props. The little people a queen, a king, a bishop, a ballet dancer, a baby, a devil who resembles Pretorius, and a mermaid were photographed separately in large-scale jars and matted into the small jars. The composites are flawless, including a scene in which the king escapes and Pretorius picks him up by the scruff of the neck and pops him into a jar.

Matte paintings adding scope to the village were provided by Jack Cosgrove, ASC and Russell Lawson, ASC.

Karloff's Monster makeup, again created by Jack Pierce, was similar to the first film's, with additional burn damage. Early in production, Karloff fell in the windmill cistern, dislocated his hip, and was heavily bandaged for the rest of the film. His performance is magnificent both in pantomime and in his limited dialogue scenes. No other actor has grasped the full potential of the role.

Colin Clive, the perfect Henry Frankenstein, is supposed to be in feeble health in the sequel and is therefore less dynamic than before, yet his nervous tension is shattering and overtones of tragedy hover around him. It wasn't all make-believe; Clive was an ill and desperately unhappy man, afflicted with acute alcoholism which led to his death at the age of 37.

As Pretorius, the tall, skeletal Thesiger delivered a singular characterization that even Rains could hardly have surpassed. In 1932, Whale had brought Thesiger to America to portray the acerbic, effeminate Horace Femm in The Old Dark House. Pretorius is a hardier extension of Femm bitchy, unpredictable and disdainful of women, his haughtiness emphasized by a uniquely sculpted nose. He is alternately hilarious and horrifying. Writers for years have pigeonholed Pretorius as gay; whether Whale envisioned him as such is debatable.

Thesiger got most of the film's best lines, many of them improvised on the set. Pretorius bombards Henry with these bon mots, which are scattered throughout the film like Oscar Wilde epigrams:

"I also have created life, as they say, in God's own image."

"Sometimes I think it would be better if we were all devils, with no nonsense about angels and being good."

"The creation of life is enthralling, distinctly enthralling, is it not?"

"Leave the charnel house and follow the lead of nature or God, if you like your Bible stories."

As the great experiment begins, he exults, "Once we should have been burnt as wizards for this experiment!" Leading his entourage into the watchtower, he tells them to "Mind the steps a bit slimy, I expect. I think it's a charming house." To the Monster's line "I love dead, hate living," he sniffs, "You're wise in your generation."

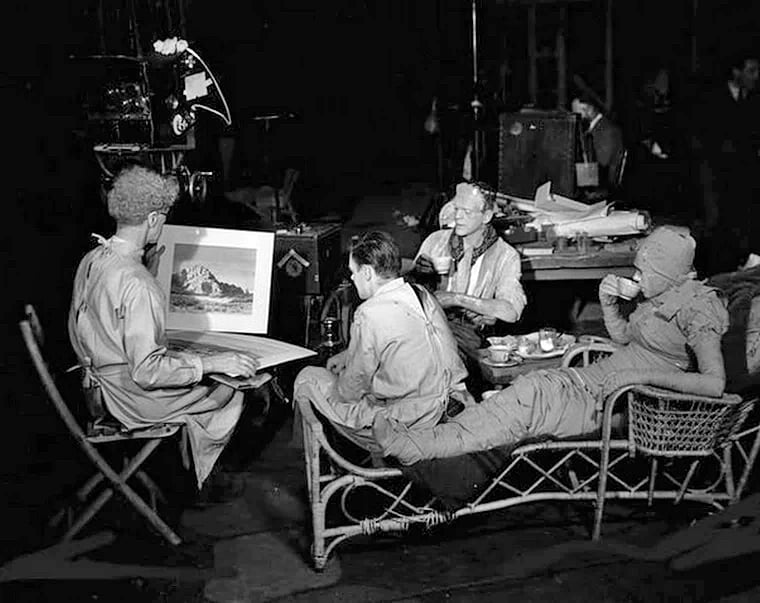

The company was a pleasant one. The English players had tea every afternoon, to the consternation of studio watchdogs. According to Elsa Lanchester, however, "Whale seemed to be jealous of all the attention Karloff got, and referred to him as 'that truck driver.'" Many publicity photos show the normally aloof Whale hamming it up on the set, upstaging his star.

While Bride was in production, Stuart Walker was directing Werewolf of London on a nearby stage. Both were closed sets. A corridor was built to accommodate Valerie Hobson, who was in both pictures. Cortlandt Hull, great-nephew of Henry Hull, star of Werewolf, tells of an amusing incident: "Henry's wife came to visit him on the set, and she was directed to the Bride set by mistake. A technician told her, 'You don't have to go around the buildings. There's a connecting corridor between the two stages.' The corridor was dimly lit. As she proceeded toward the other end, she heard 'thump! thump! thump!' Halfway through, she saw Boris Karloff coming down the corridor in full Frankenstein makeup, smoking a cigar. As they met, he said, 'Good morning, Mrs. Hull.' She shrieked, 'Aiee! Aiee! Aiee!' She knew Boris, but in the dark corridor she didn't recognize him."

Franz Waxman's score for Bride is a classic example of music being as important as visuals for setting the tone of a fantasy. The picture looks and sounds much like a Wagnerian opera, aglow with visual and sonic grandeur. Recently arrived from Germany, Waxman met Whale at a party where the director said to him, "Nothing will be resolved in this picture, except the end destruction scene. Will you create an unresolved score for it?" Waxman watched much of the shooting and created leitmotifs for the major characters. The three-note stanza from the "Bride" theme resembles "Bali Ha'i" in Richard Rodgers' later South Pacific. The score contains a minuetto for the prologue, a marche funebre, a pastorale, much exciting chase music, a triumphal march, a bone-rattling crypt sequence, the long creation sequence (now in the symphonic repertoire), and much atmospheric music. It was performed by Mischa Bakaleinikoff with a mere 22-piece orchestra, yet it is so ingeniously orchestrated that the lack of instrumental heft goes unnoticed.

Production wrapped on March 7, 1935, after running 10 days over schedule. The final cost was $397,023, more than $100,000 over budget. Much trimming followed, reducing the final cut from 92 to 75 minutes. Excised were the court hearing, a sequence in the morgue, a subplot in which Karl murders his miserly uncle and lets the Monster get the blame, and numerous bits of mayhem. A brief sequence wherein the Monster encounters a Gypsy family was inserted to cover these deletions. The prologue was pruned drastically to delete racy dialogue about past escapades.

Bride opened at the Hollywood Pantages and the New York Roxy. It got great reviews and made a lot of money, although less than Frankenstein. After looking at this marvelous film, one might wonder how many Oscars it earned. It was nominated only for sound recording and lost to MGM's Naughty Marietta.

Many have dreamed of restoring the film to its preview length. Universal Home Video technical director Ron Roloff recalls, "In 1985, because of the success of the videos of the restored Frankenstein, MCA made a worldwide search for any prints of Bride that might exist. It drew a blank. In 1992 it was rumored that the Library of Congress had unearthed a complete nitrate print that had been copyrighted in 1934. Before these rumors started, we had the print measured and compared it to what we had on the lot, and they were the same."

The dream persists. Bride is not perfect — no movie is — but perfection can be a liability. Instead, what we have is a frightening, funny and touching film.

Thanks to Cortlandt Hull; Ron Roloff; the late John P. Fulton, ASC; David S. Horsley, ASC; J.U. Miller and Harry Wolf, ASC.