Baraka: A World Beyond Words

A 70mm non-verbal film, photographed in all corners of the globe, emphasizes humankind's interconnection with nature.

By Nina Cooper

Shot in 24 countries over 13 months, Baraka is one of only a handful of 70mm feature films made in the last 20 years. Directed and photographed by Ron Fricke and produced by Mark Magidson, with music by Michael Stearns, the film has neither words nor actors, but you won't miss these familiar elements. From a snow monkey who looks hauntingly familiar to common images presented from unfamiliar perspectives, Fricke leads the viewer on an unforgettable journey where spiritual boundaries blur or dissolve completely. By juxtaposing seemingly disparate elements, he reveals that elusive current of interconnection we often sense but rarely see.

"I always felt that Koyaanisqatsi should have been filmed in 70mm, and I did not completely agree with its message," comments Fricke about the similarly image-oriented 1983 film he photographed and co-edited. "I look at the theater as a temple. The audience sits in the dark with their senses alert and their defenses down. It is the perfect opportunity to bypass the viewers' personalities and address a life-affirming message to their inner beings." Fricke previously explored this approach to filmmaking in Chronos, an award-winning Imax film that he directed, photographed, and co-produced with Magidson.

Driven by a mutual desire to create a non-verbal, globally encompassing film in 70mm, Fricke and Magidson forged a partnership that gave rise to Baraka (a Sufi word that means 'essence' or 'blessing'). "Baraka could not have been made without Mark Magidson," says Fricke. "In a studio setting, the film would have suffocated. Mark's flexibility allowed it to develop organically, and his artistic input permeates the film."

"It's almost impossible to finance a film like this," says Magidson. "When it finally came together after five years, we were on a mission: we put all the production value that we could on the screen."

Since there is no dialogue in Baraka, the images become the main characters. In order to enhance the emotional impact of nonverbal sequences, it was natural to aim for the highest image quality possible. Working with a very limited budget, Fricke knew that he would have to shoot less film in 65mm than in 35mm because of the higher negative cost. But he insists that this limitation was not a handicap, since he prefers to shoot selectively regardless of the format. (The shooting ratio in Baraka was 10 to 1.)

“Baraka is a guided meditation that explores the human experience.”

Another obstacle to shooting in 65mm was securing the camera. "The new Arri System 65 was ideal," says Fricke. "It was a great camera package, but it was prohibitively expensive to rent for a 13-month shoot." Magidson solved the problem by arranging to lease a Todd-AO camera: "Todd-AO, with its rich tradition in 65mm production, was very supportive, specifically Dick Vetter and Lee Parker."

Fricke used the Todd-AO camera for 24-frame and high-speed filming. "It proved to be very rugged and operated well through exposure to heat, cold and moisture. It held up after being dropped, bounced and otherwise abused, but there were some problems to work out." Instead of having a matched set of lenses, the Todd-AO came with an assortment of lenses from different camera systems. Although the lenses were excellent in their own right, none of them matched in contrast or sharpness, and some of them, especially the Zeiss Hasselblad still camera lenses, caused a light bounce in the shutter chamber. The Baraka team decided to modify the shutter by cutting a light-baffling system on its hub. They also built a custom 5-perf matte box system to control light entering the lenses, as well as adapters that increased the range of lenses that would fit the camera body. With these adjustments, Fricke felt that the camera was completely reliable and produced rock-solid images at any speed.

In order to achieve a degree of uniformity, Fricke generally limited himself to three or four lenses. He had to know the lenses' innate properties intimately in order to find the best lens for each situation, likening the task to working with people from several different cultures. "I had to be as diplomatic with the lenses as an ambassador negotiating a peace treaty," he jokes. For portraits, he chose a Schneider Zoom lens, which he had used for his work in the Imax format. "It was very sharp and had great contrast," he recalls. Fricke also employed the new Pentax 800, which worked exceptionally well for filming a full eclipse in Hawaii. His favorite Todd-AO lens, the 24mm wide-angle, he used cautiously: "It was very sharp and had low contrast, but there was a little vignetting and distortion on the sides."

To create the time-lapse sequences he wanted for the film, Fricke designed and assembled a new, computer-operated, 65mm motion-control timelapse camera, a more sophisticated version of a camera he designed for Chronos. It is light, small, portable, and runs on batteries. Jim Sorenson designed the camera electronics. The motion-control computer program and wiring were crafted by Mike O'Gara, John Clark and Art Tanaka of AthenaSystems. Within the camera itself, individual stepper motors control the film advance, registration pins, variable shutters and the magazine advance. There is also a stepper motor on the dolly and two more, one to pan and one to tilt, on the lightweight, custom-built camera head. A laptop computer controls all of the movements of the motors. Fricke designed the system to use Hasselblad Zeiss prime lenses in the 2 ¼ format. "They are very sharp and cover all of the 70mm formats, from 5-perf to 15- perf," he notes.

The camera's computer has programs that set the stepper motors at the appropriate rate for each 65mm format. "I can switch to 5-, 8-, 10- or 15-perf within minutes," says Fricke. To switch formats, he simply changes the aperture plate and chooses one of two mounting positions for the camera, which allows the camera to run either vertically or horizontally. He designed the camera with these features because he often works in varying 65mm formats. "It is nice to have one set of lenses and accessories that you can get familiar with," he relates.

The new camera allowed Fricke to do in-camera effects on location. "A whole section of the film was designed around photographing the night skies as an archetypal image to express the eternal," he explains. "We filmed rotating star fields at sacred places all over the world, including Egypt, Cambodia, Australia, and the United States." The night shoots were scheduled carefully during full moons so that the foreground object of each location was illuminated by moonlight. He was able to shoot both foregrounds and star fields at once by exposing for no more than one minute per frame. Filming for any longer would cause the moonlight to wash out the stars.

For the night shoots, Fricke found it very difficult to find locations without any artificial lights, and even good locations, far from civilization, were vulnerable to intruders. A mosquito-plagued crew set the camera up and filmed at f/3.5, with one-minute exposures per frame on 5296 stock, for six to eight hours each night. "If we were lucky and escaped overcast skies, car lights and guards waving flashlights, we would end up with 20 seconds of amazing screen time," he explains.

“We must recognize that we are nature and we are one. By doing so, we will salvage not only our physical world but our psychic world, the part of each of us that strives to transcend itself and commune with the eternal.”

With the new camera, Fricke was also able to shoot timelapse double-passes with pans, tilts, and dollies. He would set the exposure to film at night while the camera moved down the track, then rewind it, return the camera to its original position and expose it again for sunrise while the camera moved along the same path. The double exposure produced a breathtaking shot in which rotating stars appear in the dawn sky.

Fricke and Magidson meticulously designed the equipment package for Baraka to maximize quality and flexibility while keeping everything as lightweight as possible. A frenetic travel schedule made the delays of cargo shipping untenable. As a result, the weight factor became crucial because all the equipment had to be shipped as excess baggage. "With over 100 flights, freight was our single largest line item," remarks Magidson. In all, the shoot required 50 cases weighing a total of one ton. "Bruce Simbala, our overworked grip, had the daunting task of keeping track of all the equipment," recalls Fricke. "He must have packed those cases a thousand times. It's a miracle that he didn't lose a single case, or even a camera screw, in three trips around the world."

The filmmakers chose an Egripment/Star Track portable dolly because it was lightweight and folded into a small package. Fricke increased its versatility by motorizing one of the wheels so that the dolly could also be used with the motion-control camera. The 40' dolly track system was custom-built in lightweight aluminum and broke down into 5' track sections that could be shipped as excess baggage. The equipment package also included a Panther mini jib arm and a Continental major helicopter mount that was flown in as needed for aerials.

In addition to equipment, a great deal of film stock accompanied the crew. "We chose to carry our exposed stock for the duration of each six-to-eight-week shoot rather than sending it back for processing," says Magidson. "Either way was a risk, but in a lot of countries, we simply could not trust that the customs officials would not open the film cans. We even had a three-hole changing bag which we used on many occasions to let customs officials inspect our exposed stock."

To shoot Baraka, Fricke used 5296 and 5248 65mm stock. Most of the time he overexposed half a stop over what Kodak recommended and processed everything normally. He shot over half the film with the 96. "I chose the 96 because it matched well, it had good contrast and the blacks held up." He often had to rely on the 96 to compensate for low light because, on average, the fastest wide-angle lens available in the Todd-AO package was f/3.5. He carried only a small lighting package which consisted of a few Lowel Totas with umbrellas. Sometimes Fricke used a very large silk illuminated by four or five Totas. "It made a great soft key light," he recalls. Nevertheless, about 90 percent of the film was shot with available light.

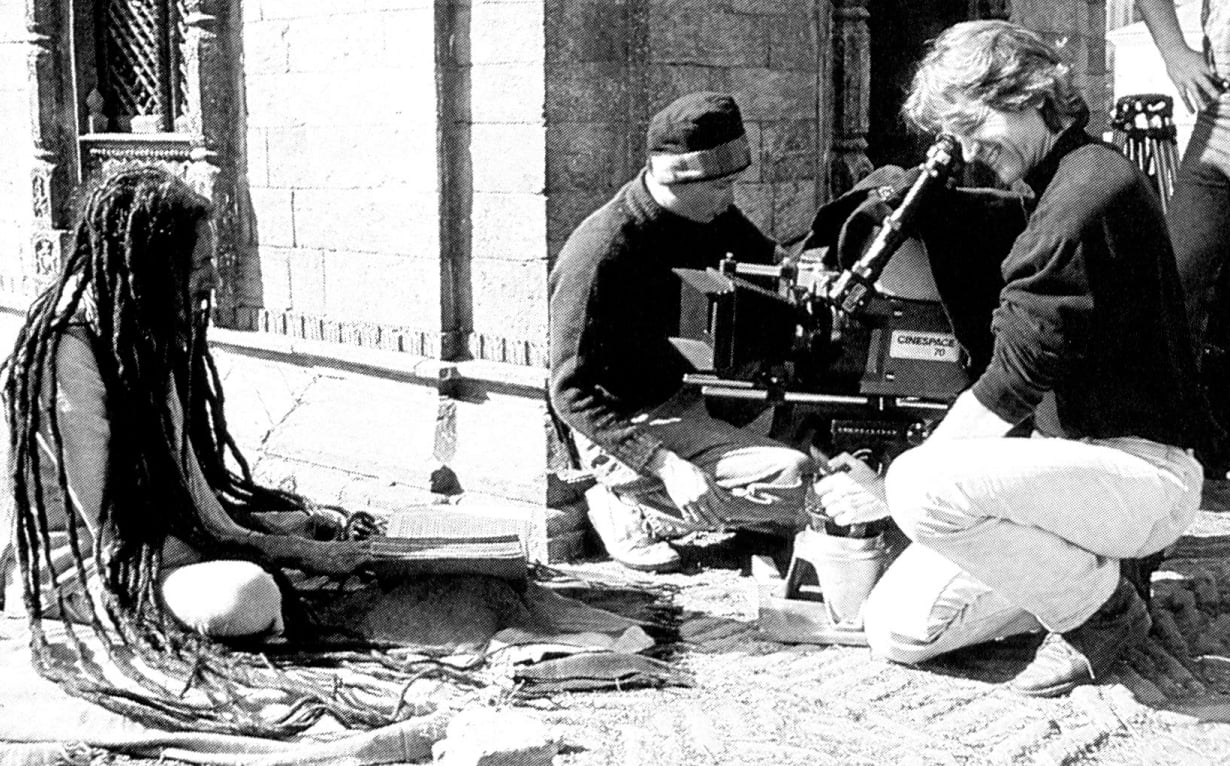

Kathmandu, Nepal. (Photo by Alton Walpole)

Since Baraka was filmed without the benefit of a large budget, the crew had to operate with a very small, well-coordinated staff. The traveling unit consisted of only five people: Fricke; Mark Magidson; supervising producer Alton Walpole (who edited Koyaanisqatsi with Fricke and was location manager/co-editor on Chronos); first camera assistant Sam Guam; and key grip Bruce Simbala. The crew was also supported by talented coordinators in Los Angeles and on location. "The cost of keeping each person on the road for so long was very high," remarks Magidson. "The small crew allowed us to stay out longer, but it put a great deal of pressure on everyone." The fact that the crew often worked day and night, sleeping only on airplanes and constantly changing time zones, also generated a great deal of stress and tension. The grueling road trips were six to eight weeks long, with only a few days of recovery time in between.

“You could say that we are privileged guests— that Life invited all of us to planet Earth, and Life didn't ask any of us to approve of the guest list.”

The crew worked locations that were often as perilous as they were diverse. "We all had close calls," says Fricke. "In Nepal, Sam passed out from altitude sickness while we were trying to shoot an aerial of Everest, and our scout plane hit an air pocket with such force that our seat belts tore open and Mark's Hasselblad still camera bounced off the pilot's head. In Brazil, Mark was almost crushed by a falling tree, and one dark night I accidentally kicked a python. Another time, one of our planes, with Bruce and Sam aboard, made a near-crash landing in the rainforest because the pilot forgot to turn on the gas tank for one of the engines."

In Cambodia, the filmmakers could hear artillery fire at night, and they had to tread carefully because the Khmer Rouge booby-trapped the temples [in Angkor Wat]. "We were very lucky that no one was hurt or became seriously ill," says Fricke. "I was asked at a press conference how we survived the shoot, and the only response I could think of was 'Pepto Bismol,' the glue that held everything together."

Bruce Simbala set up a dolly shot on a collection of skulls in

Cambodia — grisly evidence of the genocide committed by the Khmer Rouge. (Photo by Alton Walpole)

Knowing that he would be an editor on the film helped Fricke choose his shots, but he could rarely plan them ahead of time. "So much depended on the weather, how everyone felt that day and if we were able to get the right permits. On top of that, the crew had to be patient with me because I work more like a still photographer and take the time to frame each shot very carefully." Working in a nonverbal format, he points out, heightens the importance of each image: "You have to feel what the film is saying through the cinematography, editing and music." Fricke knew that he needed exceptionally powerful shots to sustain his connection with the audience for 90 minutes. "A good still photograph reveals the essence of the subject — not just the physical presence, but the inner workings as well. Non-verbal films must live up to the same standard."

Filming intimate portraits was especially difficult. In Rio and Sao Paulo, Fricke hid his camera in a van to unobtrusively film people living in the streets. On the Ganges, it was hidden in a houseboat. In Nepal, he scouted early in the morning, then re-created the street scenes he had observed the following day. Many of the dances in the film, such as those of the Masai, Balinese Kecak and Australian Aborigines, were traditional dances that were commissioned and staged at carefully chosen locations. Time-lapse scenes of crowds at Penn Station in New York City were filmed with a camera hidden in a trunk while the crew stood around pretending to be lost tourists consulting their maps.

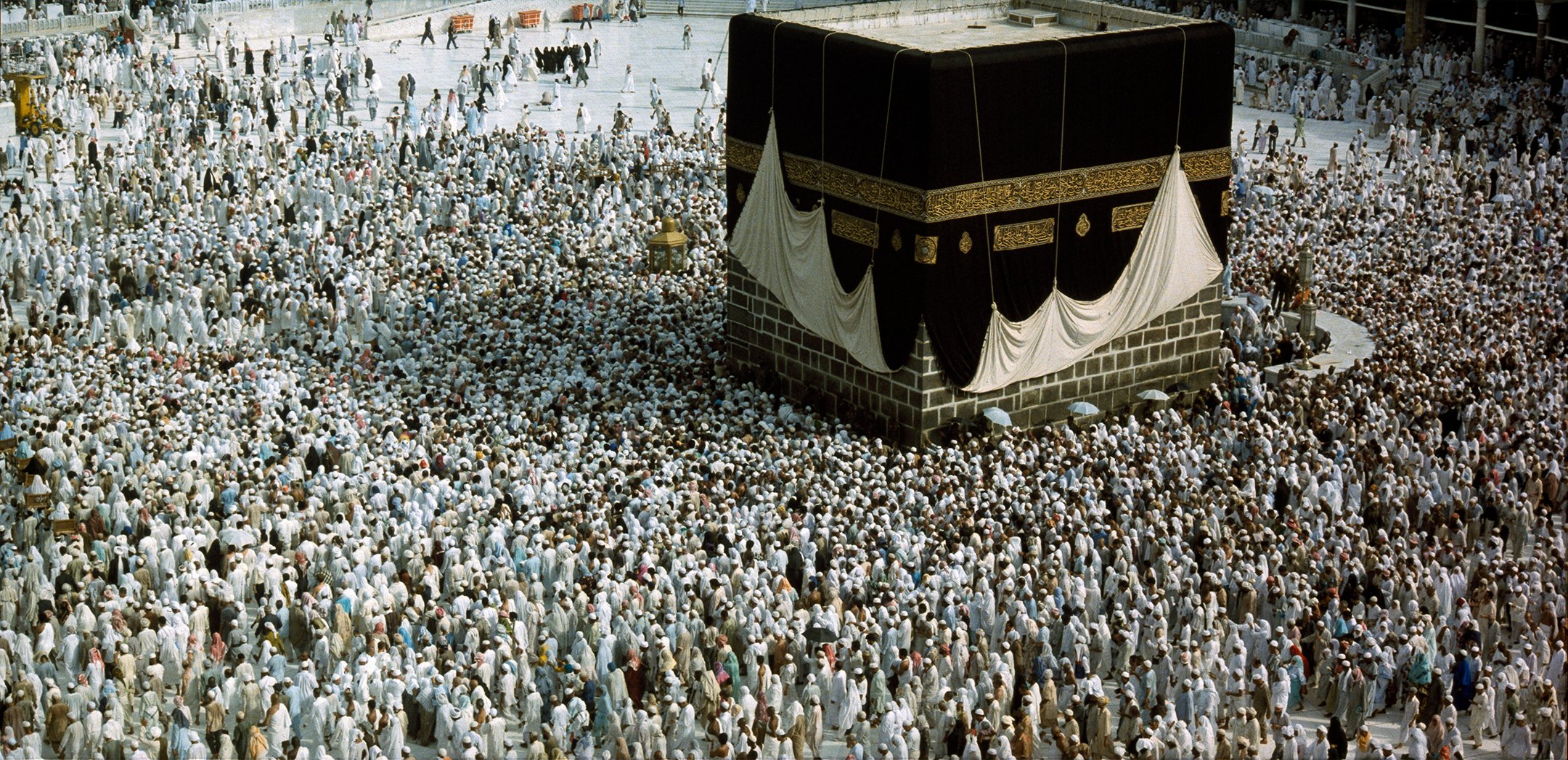

Fricke shot in all styles at all locations. The photography embraced the entire gamut of location shooting: 24 frames, high-speed, time-lapse and time-exposure time-lapse. Fortunately, the crew was already familiar with his approach to filmmaking. Guam had previously worked with Fricke on an Imax project in Singapore, and Simbala had collaborated with him in Mecca on an Imax film for the Saudi government. "Sam was always swift, efficient and clean," says Fricke. "He often knew what I needed before I said anything. Bruce was amazingly quick setting up the dolly track, and he consistently operated the moving camera everywhere. He only shot statics of very dramatic scenes. He believes that the 5-perf format is ideal for dolly moves because it hides the track, unlike other 65mm formats with less accommodating aspect ratios." While moving the camera draws the audience in, Fricke cautions that it is easy to wind up with shots that feel preachy. "You have to walk a very fine line between composition and obvious manipulation. I don't want viewers observ¬ ing the camera technique consciously — that would prevent them from experiencing the essence of the images."

Baraka was edited on a linear Case Video Editing System. "The choice was either to make a 35mm anamorphic workprint and cut in film, or make a one-light 65mm workprint and transfer it to video," says Magidson. "Editing on video was less expensive and had several advantages: we never had to run the negative through an optical printer, and once we had the 65mm workprint we didn't touch the negative again until it was cut. In addition, it allowed for three separate, self-contained workstations where each editor had all of the shots of the film available to him on tape. It was also nice to be able to screen the conformed 65mm workprint as the edit came together." The video edits were translated back to film with a program written by Lee Parker. The editors on the film were Fricke, Magidson, David Aubrey and Alton Walpole. Gay Browning was the assistant editor and postproduction coordinator.

Fricke was initially leery of editing on video. "The Case System drove me crazy at first because I had never edited on tape before. I would pound on the keys in frustration when I couldn't remember the commands. I think I would have given up on it if Gay hadn't been so patient and helpful." Once he mastered the technique, however, he quickly warmed to the process. "I will definitely use video to edit future projects. There are no bumps on the edits; everything is clean and fluid, and you can really study the motion of the images." The only drawback he noted was the need to check dailies carefully for problems like underexposure, which might not show up on video.

So what, finally, is Baraka about? As Fricke explains it, "Baraka is a guided meditation that explores the human experience." At the beginning of the film, we see meditators, indigenous peoples and organics. The images' sense of unity and balance is in direct contrast to the frantic disjointed rhythms of modern society. As the film progresses, it becomes obvious that we are at a crossroads: we can continue down the path to extinction, or we can re-establish our connection to the whole. "We must recognize that we are nature and we are one," Fricke stresses. "By doing so, we will salvage not only our physical world but our psychic world, the part of each of us that strives to transcend itself and commune with the eternal." He further notes that he wanted Baraka to have a positive frame of reference. "I don't deny the dark side, and we do explore it, but that is not the focus or primary message of the film." The images in Baraka, he says, are carefully balanced to highlight our interconnection with the universe and with each other. "You could say that we are privileged guests— that Life invited all of us to planet Earth, and Life didn't ask any of us to approve of the guest list."

Fricke plans to continue exploring the nonverbal format. The Samsara Series, which he is currently developing, will be a triptych of three nonverbal, 70mm feature-length films, each shot in 20 to 30 countries. The series will expand on the themes of interconnection and transcendence which Fricke sketched out in Baraka. The first film will focus on birth, the second on death, and the third on rebirth. Each film will stand on its own, but as a trio, they will also make a powerful statement about the ongoing cycle of life and death.

Fricke’s 70mm followup, the feature Samsara — filmed over five years in 25 countries — was released in 2011.

Baraka was selected by the ASC as one of the 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.