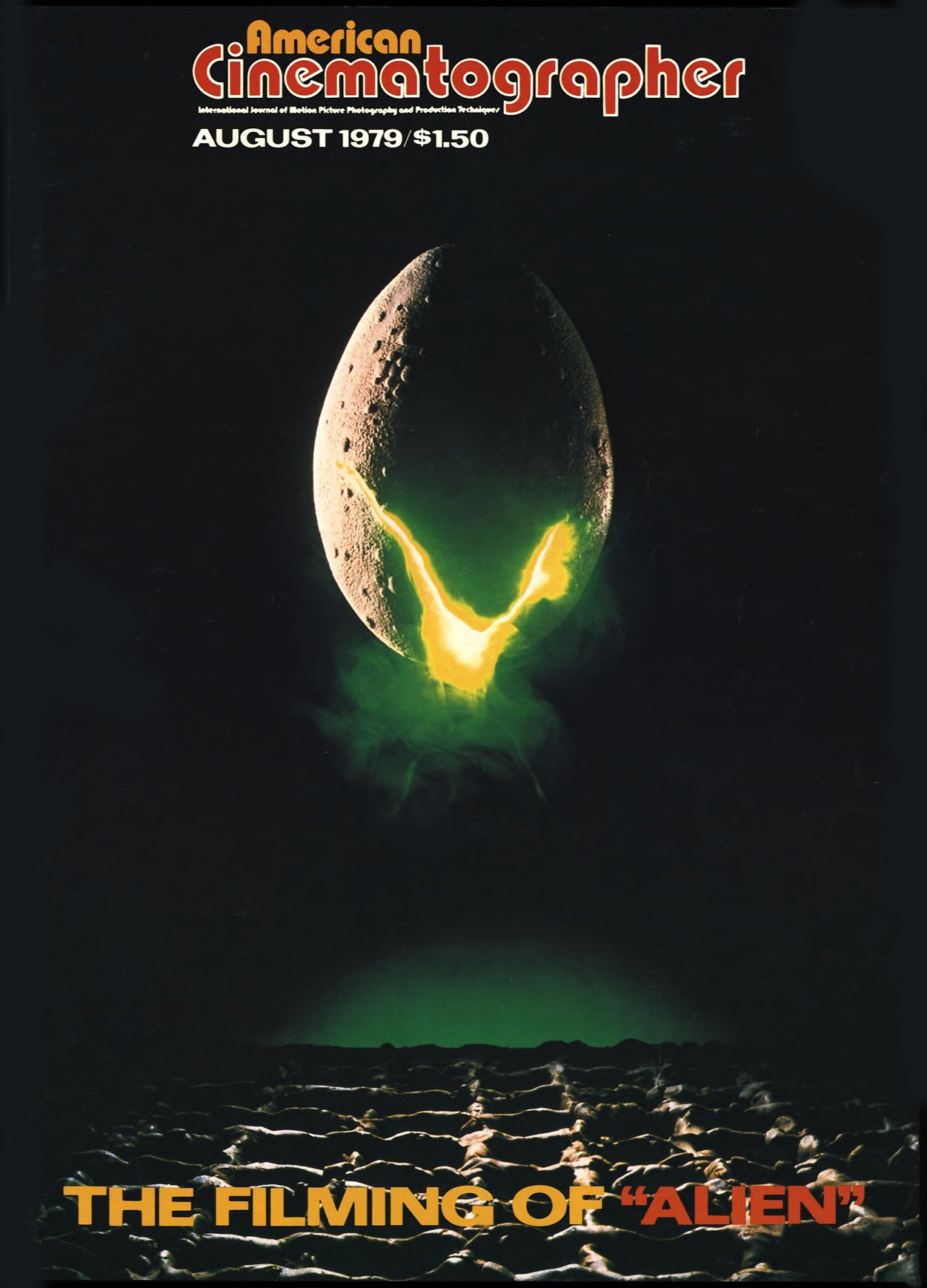

Alien and Its Photographic Challenges

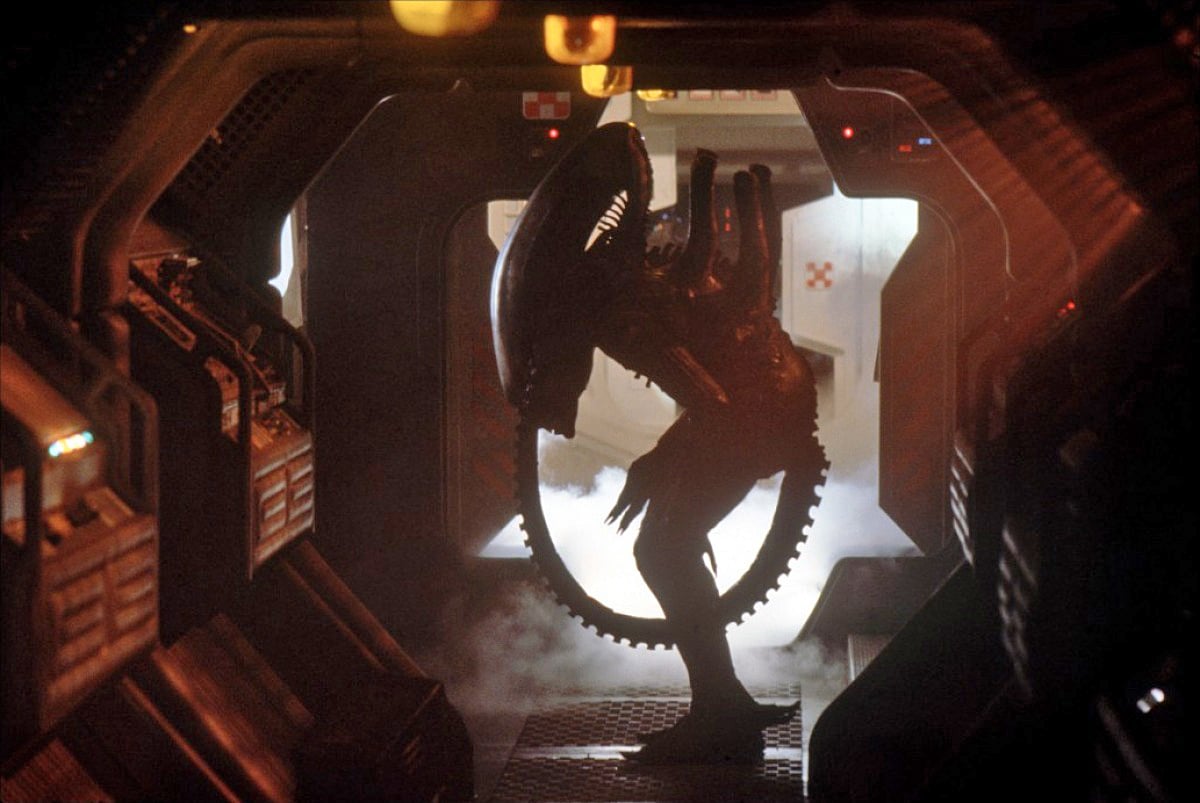

Lighting a gigantic spaceship with low-ceilinged, four-walled sets and many special effects — plus the vast terrain of an alien planet, called for methods that were out-of-the-ordinary, to say the least.

My involvement as director of photography of Alien came about as the result of direct contact with its director, Ridley Scott, over a period of years, working on advertising films.

My experience with feature films was very limited. I’d done a couple of small pictures (which I’d rather not talk about), but Alien was to be my first big feature. I had been asked to do features many times before, but had always walked away from them, based on the money difference between director/cameraman on commercials and the money they offer European cameramen to do American films. However, Ridley is a very talented guy and a very graphic director and has always been fun to work with. Since he was to be involved, I knew from the word go that the picture would end up looking nice and that it would do me no harm whatsoever to be involved in it.

I’m not a technical cameraman. I’m very much a “put it up, look at it and light it” person. I can’t go into vast detail about how I pre-plan this and pre-plan that. In Alien the way everything looks is the result of discussions with Ridley — how he felt about the visual aspects of certain scenes, the lighting style that was dictated, the particular mood of the moment in relation to the sets that were involved.

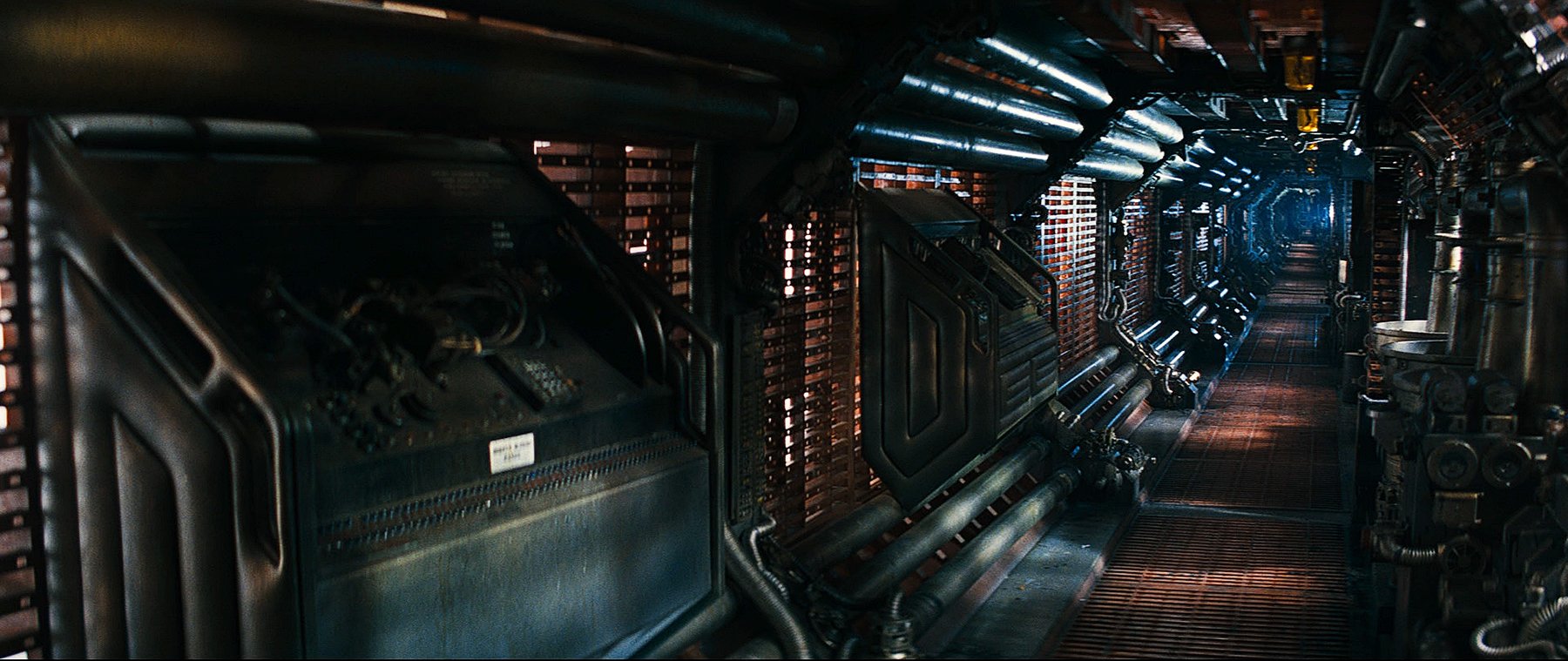

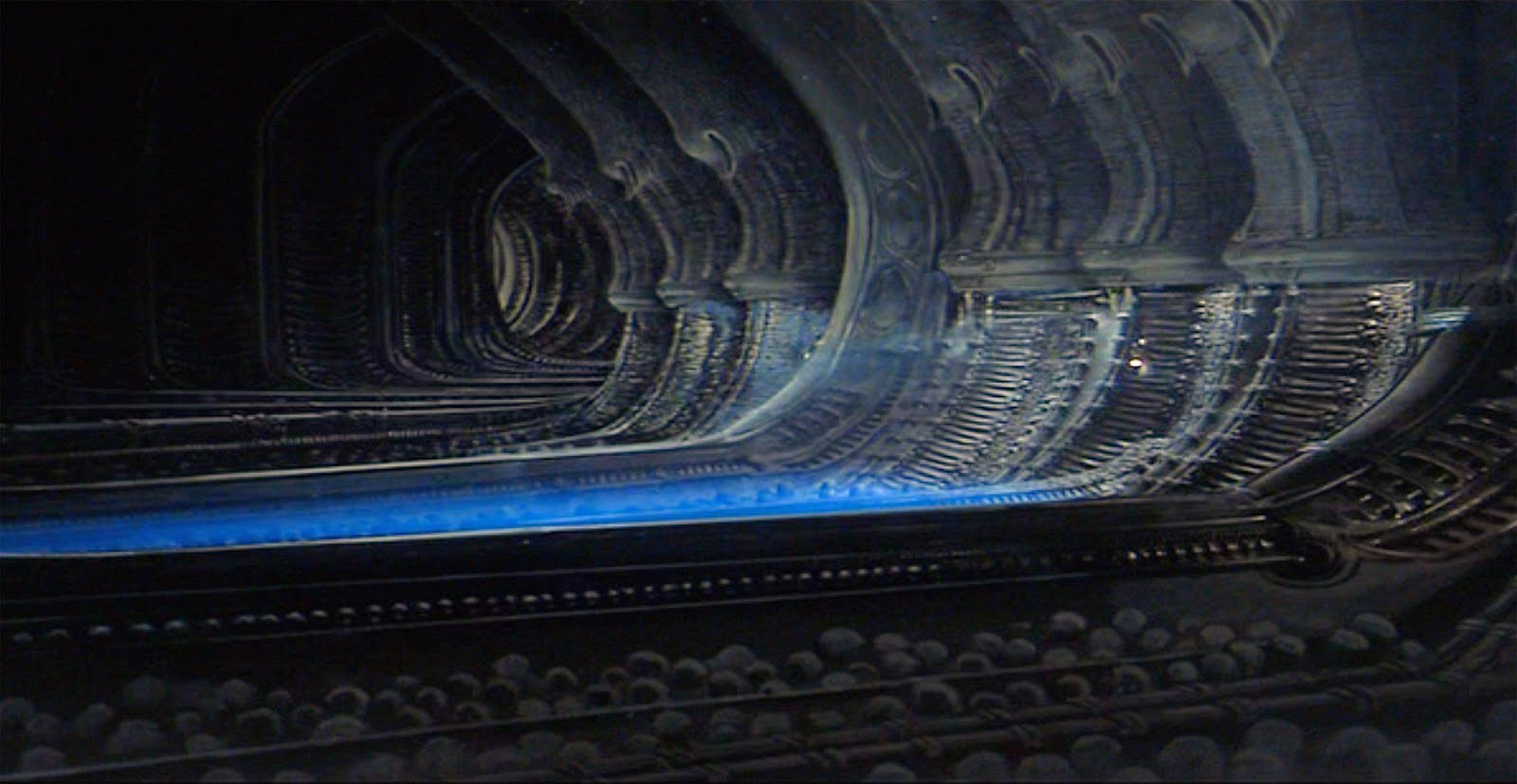

The sets and corridors were all built with very low ceilings. They were four-wallers, so that meant lighting through grills or hiding lights or having in-shot lamps. I think the look of the film is due to the nature of the sets, plus the fact that I could light with non-conventional equipment‚ such as 747 aircraft lights, “panic” lights, a certain amount of neon and fluorescent units, and a great deal of special effects light.

We did very limited tests, unfortunately, on fluorescents before we started shooting, and we could have done with starting two weeks later than we actually did. The construction manager, Bill Welch, asked for the picture to be put back two weeks, but because of bookings and distribution schedules we had to go ahead on the date that had been set. This did create some problems for me in that I had to have three crews on at once throughout quite a good part of the picture — rigging, de-rigging and pre-lighting. I suppose a lot of people have experienced that.

It was a big challenge but, fortunately, I had a good lighting gaffer, Ray Evans, who gave me excellent support. The two giants in England, Samuelsons and Lee Lighting, were very, very helpful to me, knowing that it was my first feature, and they did come forward with quite a few suggestions in terms of equipment and lighting that would go into certain restricted spaces.

Ridley had done one feature before, The Duellists, which had received quite good notices and, as a result of that film, he got Alien to do. I think producers are basically nervous at the outset about schedules and getting finished on time, so for the first three weeks or so, until they saw things on the screen, it was all a bit nervy. After the first three weeks, when I think the people back in America realized that the picture had a good style, things eased down a bit. Not having experienced big features before, I don’t know whether this kind of feeling prevails on every picture, but I found it a bit more nerve-wracking than doing commercials.

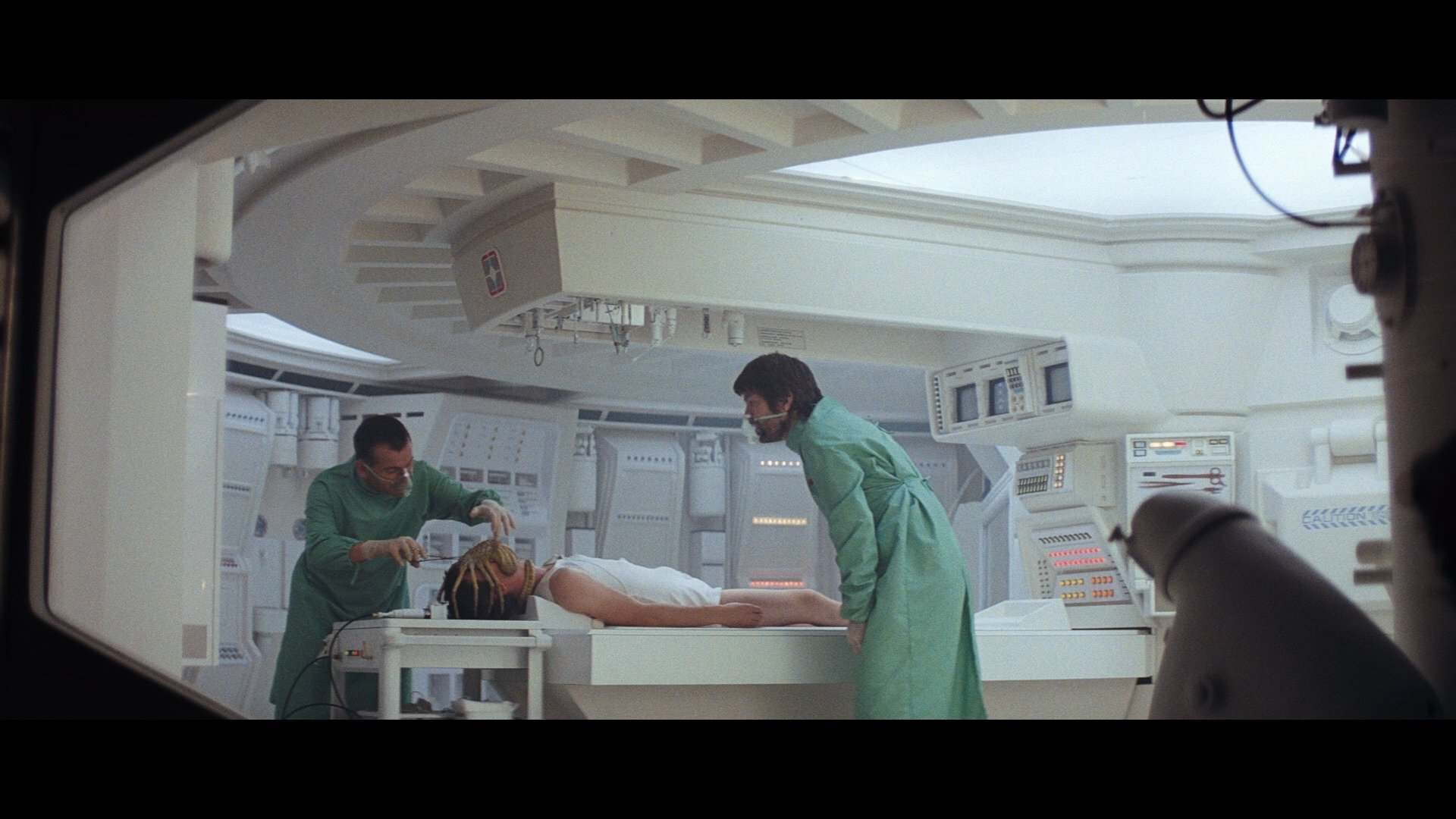

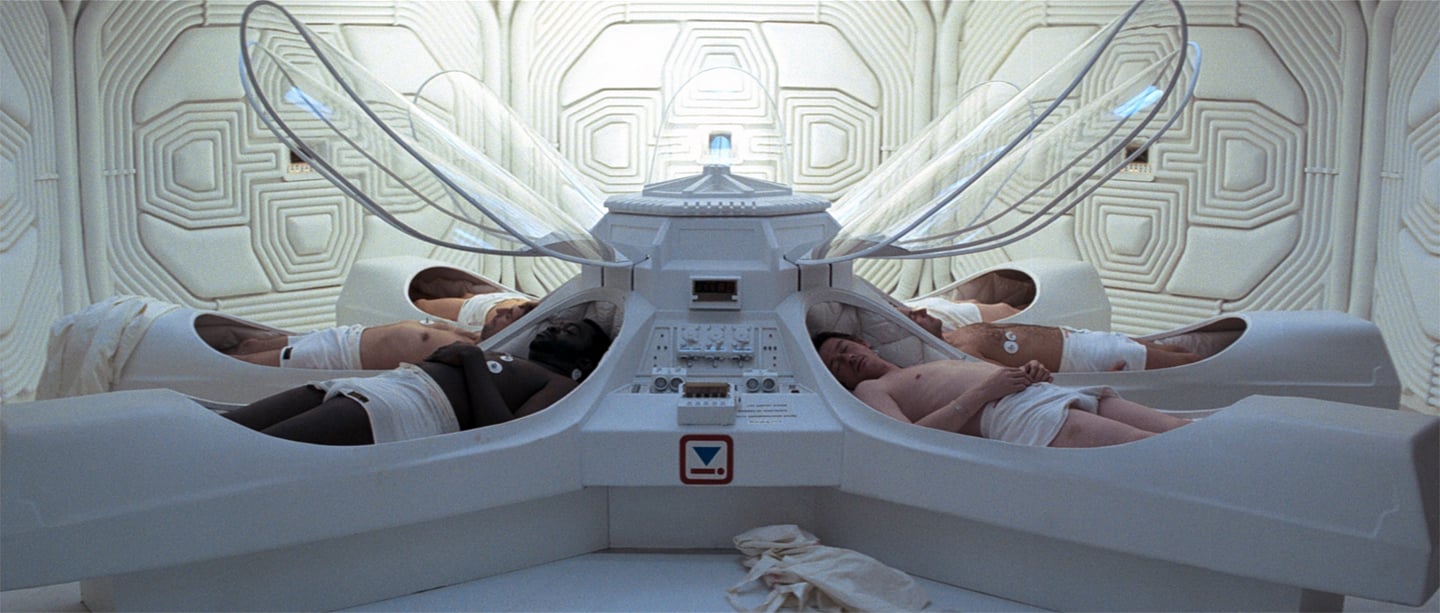

The governing factor in establishing a lighting style for Alien was the requirement that there be three levels of light — the ship before people came out of deep sleep, a working level of light for the ship when the ship goes bananas and all of the conventional light sources are going out, one had to create the impression that the illumination was coming from explosions, panic lights and things like that.

I’m a reasonably low-light photographer under normal conditions, but I had to work at even lower levels for the neon-lit scenes. In addition, there were the low ceilings, close walls and high percentage of camera movement to be taken into consideration. We were also using two cameras during most of the picture, shooting our crosses at the same time — so, whereas I normally key from ¾ back, it was virtually impossible to do this with the two-camera technique — especially since we were shooting anamorphic and had to worry about keeping lights out of the shot. One had to be able to sort of cheat lights through grids and use practicals that actually existed in the shots, but most of the time there was the necessity of overriding the fluorescents, because of the problems we all experience with mixing fluorescent and normal incandescent light.

I found a reasonable balance level between the ordinary warm-glow fluorescents and putting something like a half-blue on the incandescent lights and using a very gentle gelatine, like an 81B to knock out a little of the blue. But dimmers and things like that helped tremendously on the incandescent lights. The flames from flamethrowers held close to faces were, I suppose, a bit unpleasant for the artists, but they were very, very good about it.

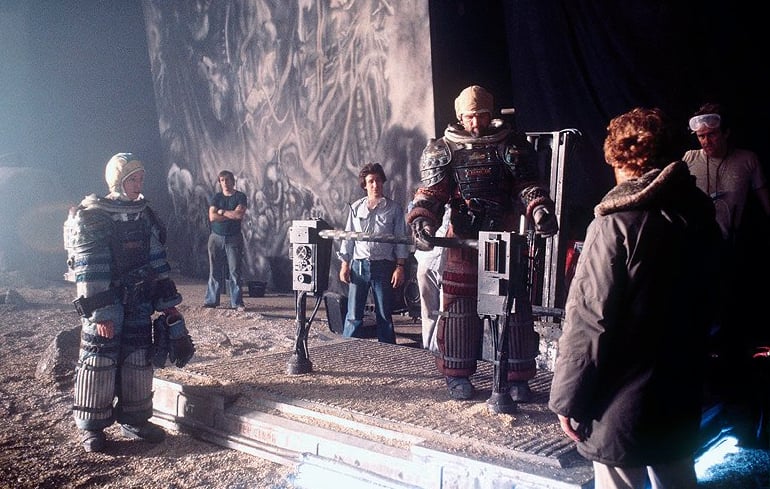

For the planet sequences, where they touched down looking for the source of electrical impulses that the spaceship was receiving, I used a couple of searchlights and a light that has become lovingly known in England as the “Wendy Light.” It was designed by Bill Chitty and built by Lee’s for David Watkin [BSC] to use in lighting the night exteriors for Hanover Street. This merely meant that I could cut down on the number of lights needed to light H Stage. Several people were a bit wide-eyed when they saw how few Brutes I had on the stage for lighting the whole thing, but the effect worked quite nicely. The searchlights gave me the possibility of playing them on long shots and I don’t think anyone notices too much that I panned them around a bit.

Just to kind of define the Wendy Light: It is a whole series of quartz bulbs made up in four panels. I seem to recollect something like 81 bulbs per panel, times four, and I had to be pulled up on chains. It’s a pretty impressive light and it blew a lot of people’s minds when they saw it going into the studio. As I’ve said, it was designed as an exterior night light and I think they lit three streets with it in one mean go on Hanover Street. For us this light really was a great time-saver. When you are working basically with only three lights on a huge set it does make life easier than when you have a whole series of Brutes that can keep getting into the shot.

In addition to Alien being my first big feature, it was also my first real experience with the anamorphic format, and it took a few days for me to get used to it. At first I hated it, because I like to box my lights in very, very tight to people — and because of the nature of the lights I like to use and the particular style I work with. However, after a few days I got used to it and loved it, Frankly, I found it very difficult, when I went back to the commercials, to get used to the smaller format. It’s a bit like an Englishman who goes abroad and drives on the right-hand side of the road; it seems to be more difficult to get used to driving on the left when he goes back to England. At least, that’s been my experience.

There was a great deal of discussion prior to the start of filming about light levels and the synchronization of the TV monitors that were spaced all around the ship, in the mess area and through the corridors. Very early on I suggested that we should shoot the picture at 25 frames rather than 24, which would put us in a kind of automatic sync and save us messing around with shot widths. It would just be a question of bar lines. I think there was no problem at all where the PVSR camera was concerned. We were using the PVSR mainly and, at times, the Panaflex. I forgot the reasons why we seemed to have to wait to get rid of bars and things, but all-in-all, it was quite efficient. One or two times, when the spaceship was blowing up, we did go out of sync with it, but we knew we were out of sync and left it that way, because with the running bar line in the middle of the picture, it helped accentuate the panic and chaos that were going on in the ship, and that things were not as they should be — so it was quite a useful graphic.

Throughout the picture we had two operators. Ridley operated principal camera and I operated second camera. We tried to work out all sorts of tracking devices to get through the corridors with their limited widths and sharp bends, and we had a really sweet guy come in and demonstrate the Panaglide, but we felt that within our time limitations it would take us too long to get used to it, and we really wished to operate the cameras ourselves.

For our pre-title sequence, we did put tracks down and used a Fisher dolly. It looked quite nice. But most of the other movements were too fast or too wide to use tracks, so a lot of hand-holding was done. Most of the hand-holding, especially the panic stuff, was shot by Ridley, who’s a bit more physical than I am and quite good at running backwards. He fell on his seat a few times, but generally it worked out quite well.

We had originally pre-planned a general set lighting for quite a good part of the spaceship, in order to avoid taking time to light each setup individually. I had worked it out with Ridley and Mike Seymour, our production designer, that with certain light panels and with selected sections of the ceiling covered in plastic, we would use quite a lot of overhead light coming down to blend with the floor light. However, it didn’t quite work out the way we planned, because the actors, while very, very good, were laid-back types who tended to work out where they were going to stand and how they were going to make exits. More often than not they ended up in very muddy areas, and the way we hoped would work — speeding through with one-set lighting — just didn’t happen. I think it was a slight pot dream on our part to begin with, because it could never work for us that way.

Another factor that had to be considered was that we had a black actor (Yaphet Kotto) in the cast, and one obviously had to bring the light up on that sort of skin and use reflective light. It was a slightly harder quality of light than I usually like to use, but it was very, very necessary — especially in low-light areas.

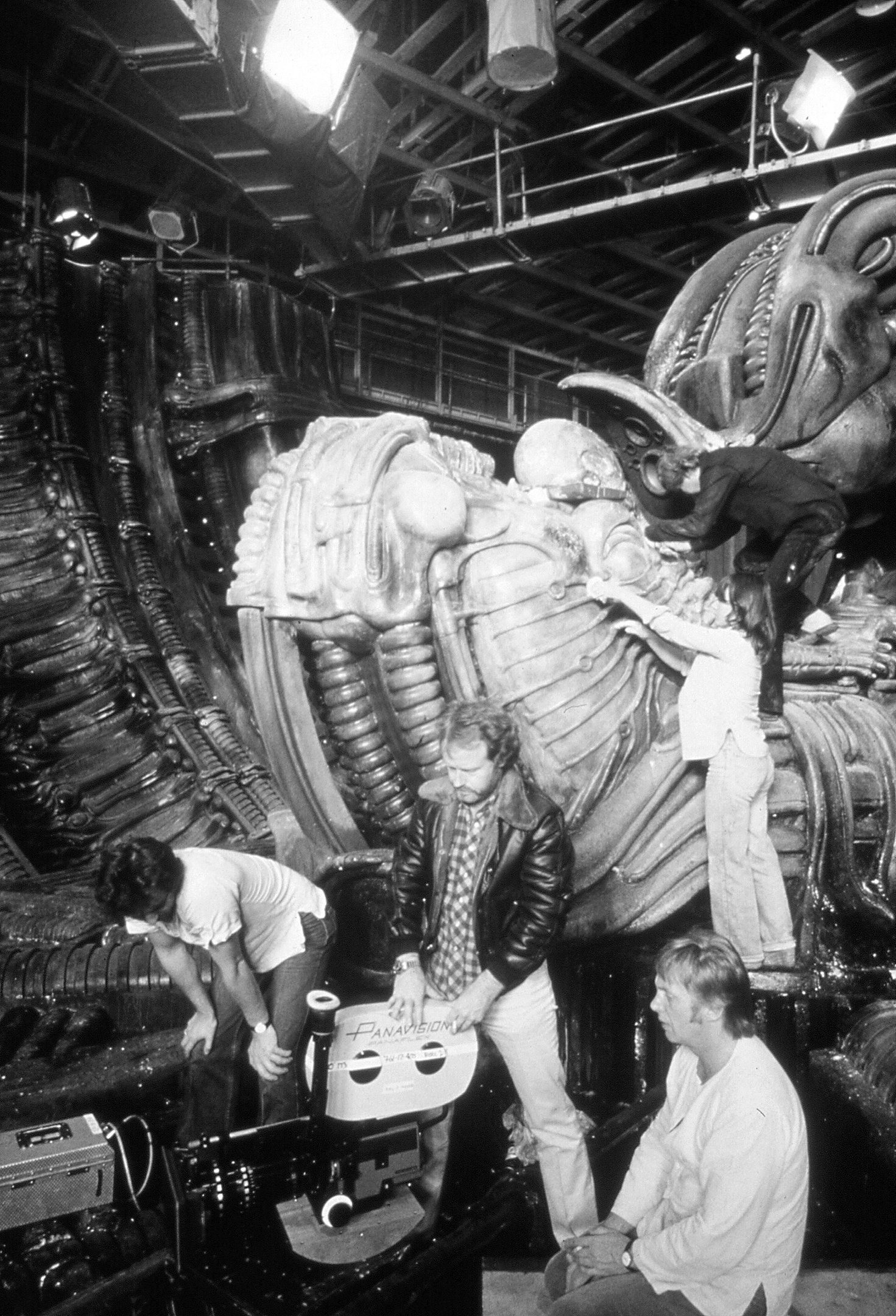

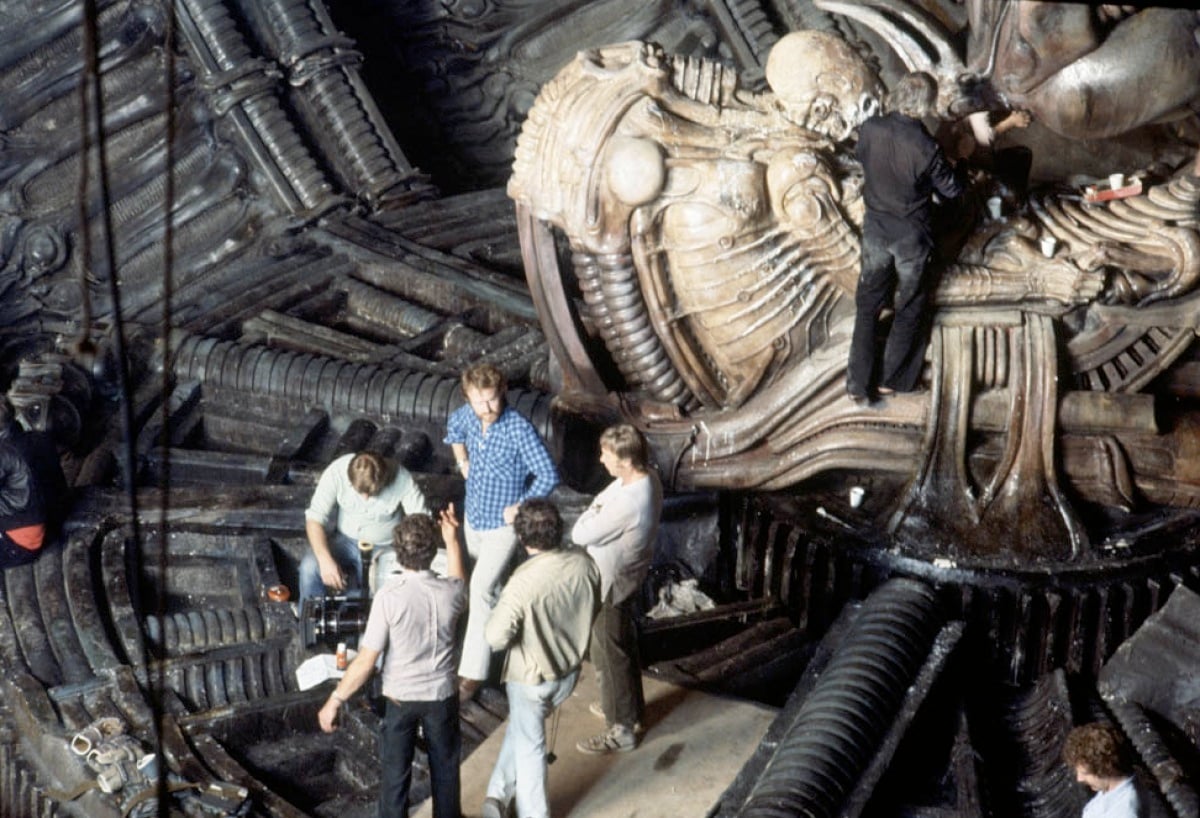

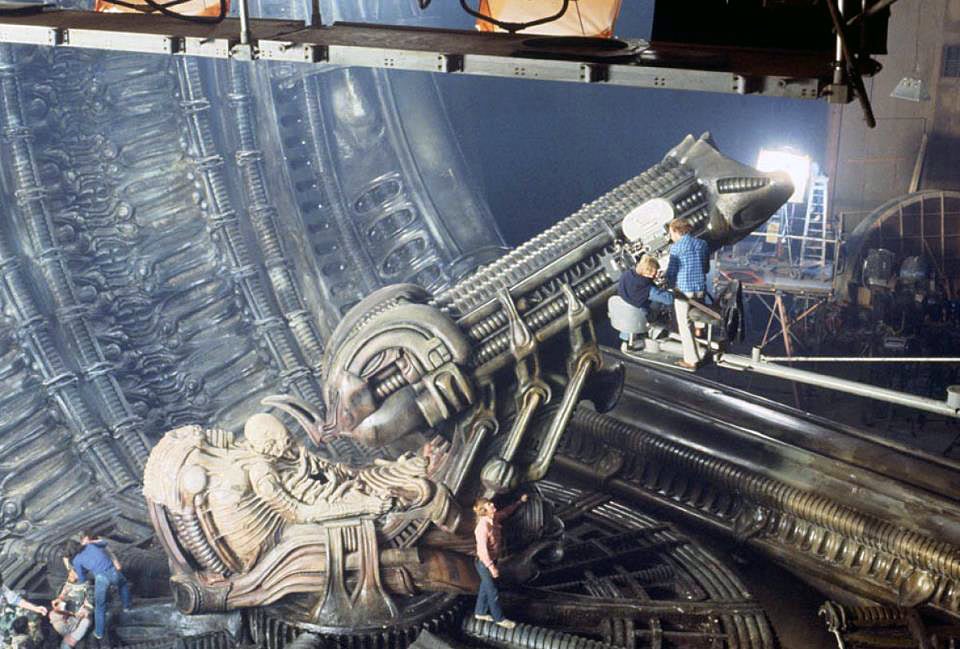

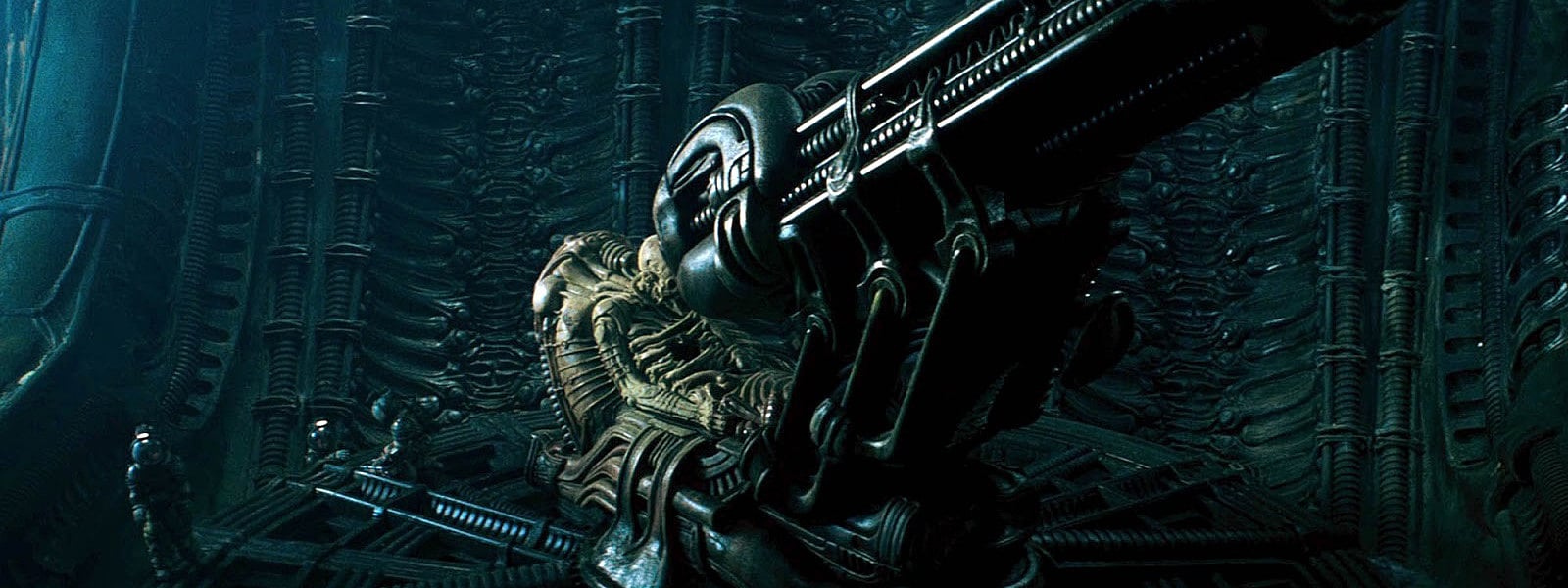

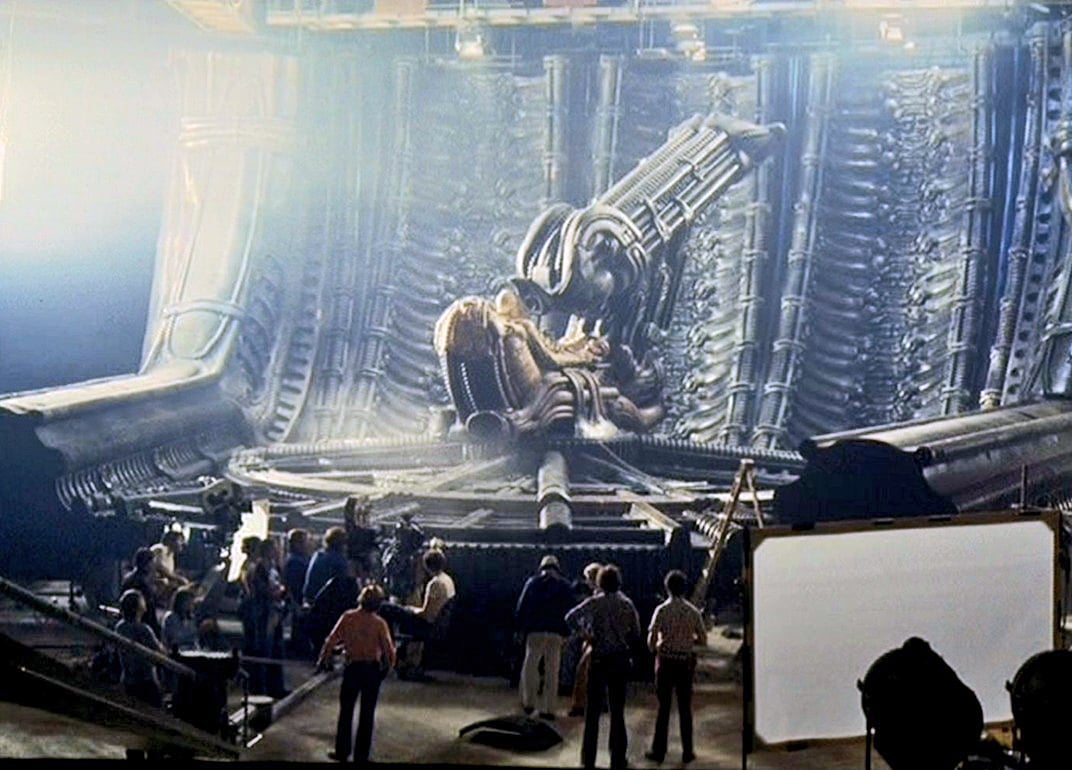

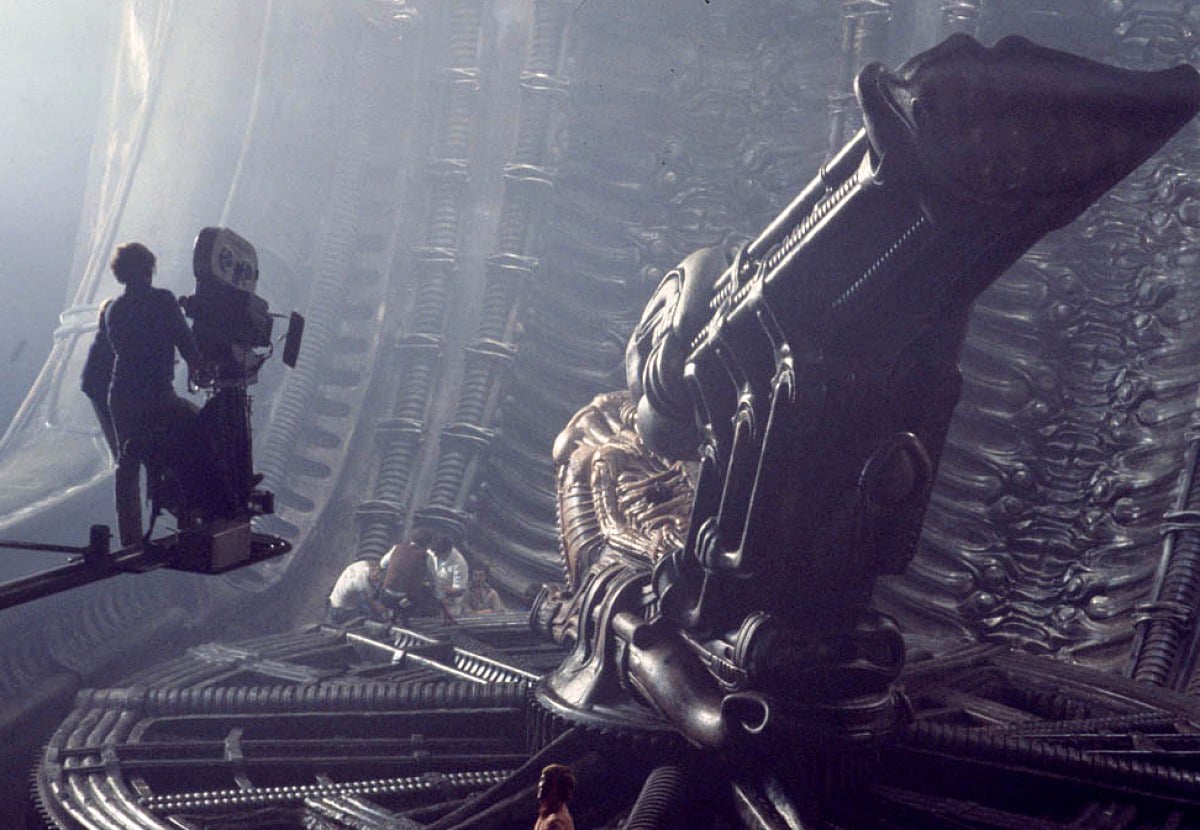

Once again, being sort of new to feature filming, I was absolutely intrigued by the matte shot kind of developments that were taking place on H Stage. I had a section of the derelict spaceship 100 feet across by 30 feet high which, once we decided the actual shape of the shop, where the light would be hitting it and how the matte artist would build onto it, was easy to light because of the nature of the surface. We also kept everything wetted down all the time and the ¾ back to backlight that I was using was absolutely emphasized by the water.

When I first saw the giant derelict vehicles set on the storyboard it frightened the life out of me, but once you switch that first light on, you find that it’s the same as any other set — only bigger. While reading the script and seeing the artwork for those giant sets on the planet initially worried me, the real difficulties were encountered in the light, small setups where people moved around a great deal — especially since you were covering them with two cameras and had television monitors in the scene to worry about.

I think that in one or two instances I could have put in a bit more fill than I did but when I saw Gordon Willis [ASC]’s Interiors it made me feel a lot happier to know that there was someone else who was coming down to that kind of key.

During the sequence where the spaceship is blowing up, most of the light was coming from spinner lights, which are like the panic lights that you put on top of your car at night if it is broken down. In fact, they gave me more illumination than the approximately 15 10Ks on trip switches that I had pushing through the side of the grill. They never had a chance to come up to maximum because the grills cut out 60% or 70% of the light and we were also beaming them through tracing paper to sort of hide the fact that we were using, in fact, packing case grills put together.

For that blowing up sequence I was also using what we call “scissor arcs,” which are open arcs with two carbons coming together and being pulled apart manually, without any mechanism at all. They are the lights we use for lightning effects. They produce just a series of flashes, but make a hell of a noise. During that sequence I noticed that Ridley used the sound of the scissors arc for one of the explosions.

Photographically, the final look of Alien, especially in terms of light direction, bears no relationship to my kind of advertising show reel, where I use a great deal of diffusion and really go pretty heavily into putting tracing paper and Plexiglas in front of my lights. As far as possible, when everything was alright aboard the spaceship, I tried to make the lighting look as though it was coming from natural sources. But when the ship was ready to blow up, the low level and extreme movements made it necessary for me to use more hard light than I normally use. But this was the effect that was required for the mood of the picture, and it was vastly different from anything I had done before. I was quite pleased with the finished result.

In the communications room of the spaceship, where Tom Skerritt talks to Mother, there were I forget how many thousands of little bulbs covering the walls, and the actual color tone was governed by the bulbs we were using in there. They were well down in color temperature — somewhere around 2000 degrees Kelvin. I came in through the ceiling with something like a 1000-watt lamp diffused through tracing paper and with a half-MTA gelatine to keep it kind of yellow, so that it looked like the room was lit by the actual small bulbs. I put very little additional light in there, but we did put the image from a 16mm projector onto the faces of Skerritt and Sigourney Weaver while they were in there, in order to simulate the reflection from a television monitor. It was a piece of film with a few numbers on it and a lot of black and splashes of varnish.

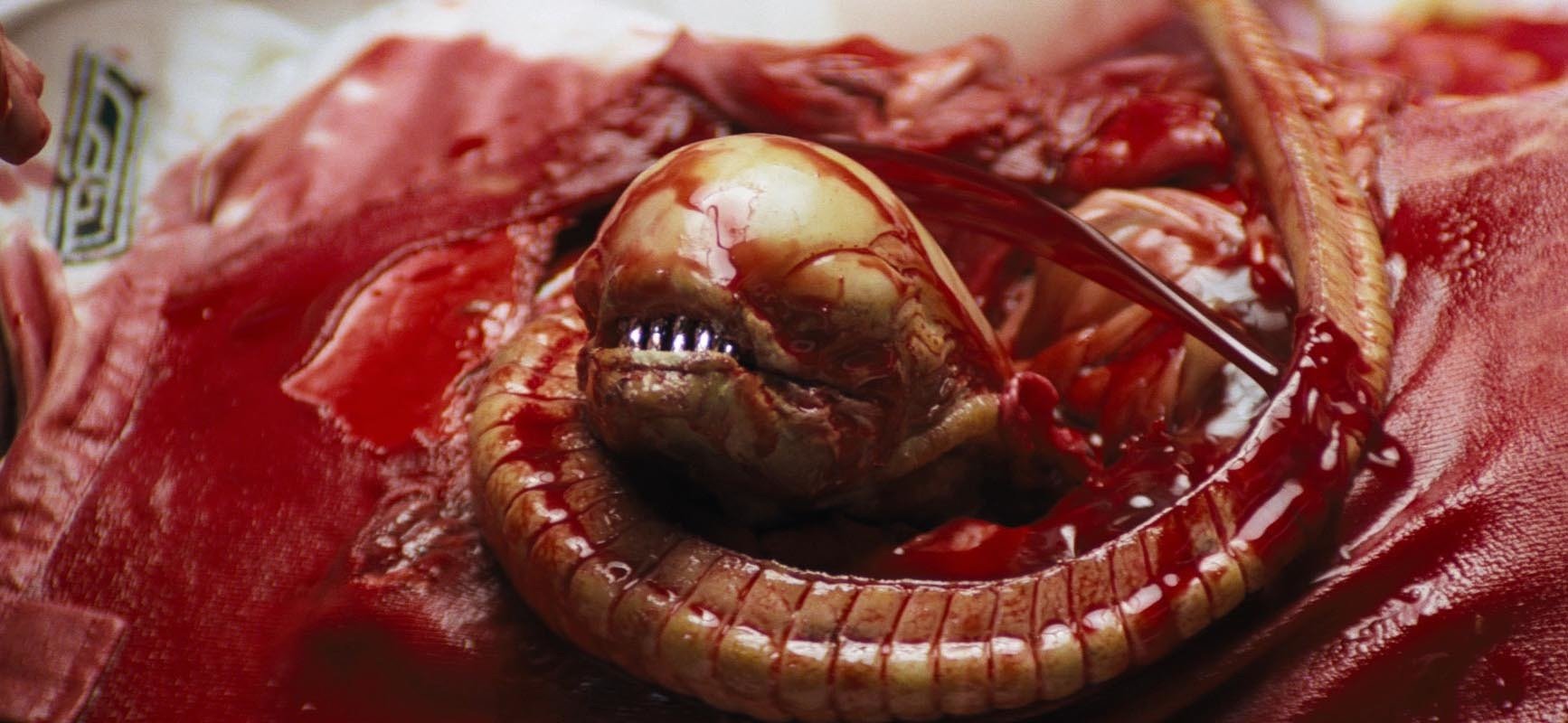

For the sequence showing the eggs in the hold of the derelict vehicle, we used a kind of general light and then put a laser across the top of the place and a lot of smoke into the set. Then we took the camera up and down through the laser beam. It was great fun, but I wish we’d had a bit more time to experiment. The sequence was shot right near the end of the schedule when time was short and we had people on our backs to get off the set so that they could revamp the eggs. One of the eggs had a top that opened for a hand model to come through with a few pounds of liver and a sheep’s stomach and David Watkins in particular, seemed to absolutely thrive on that sort of thing.

There was a separate egg that we played around quite a bit with, trying to get the shape inside it to move. We bought a hand puppet in rubber with claws and we put it on a platform so that I was able to get a light underneath it and behind it. It frightened the life out of me when I saw it in the rushes.

When we did the chest explosion for the first time (the sequence at the beginning of the film that special effects did so well) we showed some pretty hairy things. It’s the first time I ever had to walk out of rushes and, funnily enough, it was the footage from the camera I was shooting. It was just the welter of blood that got all over Veronica Cartwright when the creature came through the chest that I couldn’t take. I went out and was rather ill — and I was ribbed quite a bit about that for the rest of the picture.

I had a very short time before shooting started to do tests, but I did very little more than test equipment because the sets were not finished until the day we actually started. The stuff that I had pre-rigged, unfortunately, had to be moved out because ceilings had to be dropped in and there were masses of carpenters and painters at work.

Our first sequence, after the characters had awakened and come out into the cabin of the spacecraft involved tucking 500-watt and 1000-watt spotlights under seats and the poor devils who were acting had to climb over these lamps and, at times, must have got their knees very, very warm, but they were quite good about it.

The alien sequence in the escape craft I photographed with a CSI spot with a dimmer on the front. It was a direct spotlight to give a general strobe effect. Also, if I remember correctly, I was using about four of the ordinary strobe flashlights — all of them fixed to a kind of very, very small stomach dolly to give an out-of-sync, random strobe effect. So it was a mixture of half-frame exposures and full-frame exposures not at any particular time interval. I thought it looked very, very good in the escape vehicle when the creature climbed out of the wall. It was a bit difficult for people to work in, because they ended up getting quite dizzy over a period of time. I remember that when we were setting up in the escape vehicle we had to switch them off, because they were the principal source and one became very, very dizzy with them.

Photographing Alien was for me a unique and challenging experience, but also a stimulating one. The audiences seem to be responding to the film as we had hoped they would, and I’m quite pleased with the result.

Read director Ridley Scott’s personal take on this complex production here.

Alien was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.